Ambassador Alfredo Toro Hardy examines, in this excellently analysed paper, the self-created problems that have contributed to America’s declining influence in the world. As he rightly points out, America helped construct the post-1945 world order by facilitating global recovery through alliances, and mutual support and interweaving the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments. The rise of neoconservatism following the end of the Cold War, particularly during the Bush years from 2000 to 2008, led to American exceptionalism, unipolar ambitions, and the failure of American foreign policy. Obama’s Presidency was, as Zbigniew Brezinski said, a second chance for restoring American leadership but those gains were nullified in Donald Trump’s 2016-20 presidency leading to the loss of trust in American Leadership. In a final analysis that may be questionable for some, Ambassador Alfredo sees Biden’s administration returning to the path of liberal internationalism and recovering much of the lost trust of the world. His fear is that it may all be lost if Trump returns in 2024. – Team TPF

TPF Occasional Paper 9/2023

Trump followed four years later by Trump: Would America’s trustiness and system of alliances survive?

In seeking his second nonconsecutive term, former President Donald Trump will start out in a historically favourable position for a presidential primary candidate. Jonathan Ernst/Reuters. fivethirtyeight.com

According to Daniel W. Drezner: “Despite four criminal indictments, Donald Trump is the runaway frontrunner to win the GOP nomination for president. Assuming he does, current polling shows a neck-and-neck race between Trump and Biden in the general election. It would be reckless for other leaders to dismiss the possibility of a second Trump term beginning on January 20, 2025. Indeed, the person who knows this best is Biden himself. In his first joint address to Congress, Biden said that in a conversation with world leaders, he has ‘made it known that America is back’, and their responses have tended to be a variation of “but for how long?”. [1]

A bit of historical context

In order to duly understand the implications of a Trump return to the White House, a historical perspective is needed. Without context, it is difficult to comprehend the meaning of the “but for how long?” that worries so many around the world. Let’s, thus, go back in time.

Under its liberal internationalist grand vision, Washington positioned itself at the top of a potent hegemonic system. One, allowing that its leadership could be sustained by the consensual acquiescence of others. Indeed, through a network of institutions, treaties, mechanisms and initiatives, whose creation it promoted after World War II, the United States was able to interweave the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments. Its alliances were a fundamental part of that system. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, though, the Soviet Union established its own system of alliances and common institutions.

In the 1970s, however, America’s leadership came into question. Two reasons were responsible for it. Firstly, the Vietnam War. The excesses committed therein and America’s impotence to prevail militarily generated great discomfort among several of its allies. Secondly, the crisis of the Bretton Woods system. As a global reserve currency issuer, the stability of the U.S. currency was fundamental. In a persistent way, though, Washington had to run current account deficits to fulfil the supply of dollars at a fixed parity with gold. This impacted the desirability of the dollar, which in turn threatened its position as a reserve currency issuer. When a run for America’s gold reserves showed a lack of trust in the dollar, President Nixon decided in 1971 to unhook the value of the dollar from gold altogether.

Notwithstanding these two events, America’s leadership upon its alliance system would remain intact, as there was no one else to face the Soviet threat. However, when around two decades later the Soviet Union imploded, America’s standing at the top would become global for the same reason: There was no one else there. Significantly, the United States’ supremacy was to be accepted as legitimate by the whole international community because, again, it was able to interweave the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments.

Inexplicable under the light of common sense

In 2001, however, George W. Bush’s team came into government bringing with them an awkward notion about the United States’ might. Instead of understanding that the hegemonic system in place served their country’s interests perfectly well, the Bush team believed that such a system had to be rearranged in tandem with America’s new position as the sole superpower. As a consequence, they began to turn upside down a complex structure that had taken decades to build.

The Bush administration’s world frame became, indeed, a curious one. It believed in unconditional followers and not in allies’ worthy of respect; it believed in ad hoc coalitions and “with us or against us” propositions where multilateral institutions and norms had little value; it believed in the punishment of dissidence and not in the encouragement of cooperation; it believed in preventive action prevailing over international law.

In proclaiming the futility of cooperative multilateralism, which in their perspective just constrained the freedom of action of America’s might, they asserted the prerogatives of a sole superpower. The Bush administration’s world frame became, indeed, a curious one. It believed in unconditional followers and not in allies’ worthy of respect; it believed in ad hoc coalitions and “with us or against us” propositions where multilateral institutions and norms had little value; it believed in the punishment of dissidence and not in the encouragement of cooperation; it believed in preventive action prevailing over international law. Well-known “neoconservatives” such as Charles Krauthammer, Robert Kagan, and John Bolton, proclaimed America’s supremacy and derided countries not willing to follow its unilateralism.

But who were these neoconservatives? They were the intellectual architects of Bush’s foreign policy, who saw themselves as the natural inheritors of the foreign policy establishment of Truman’s time. The one that had forged the fundamental guidelines of America’s foreign policy during the Cold War, in what was labelled as the “creation”. In their view, with the United States having won the Cold War, a new creation was needed. Their beliefs could be summed up as diplomacy if possible, force if necessary; U.N. if possible, ad hoc coalitions, unilateral action, and preemptive strikes if necessary. America, indeed, should not be constrained by accepted rules, multilateral institutions, or international law. At the same time, the U.S.’ postulates of freedom and democracy, expressions of its exceptionalism, entailed the right to propitiate regime change whenever necessary, in order to preserve America’s security and the world order.

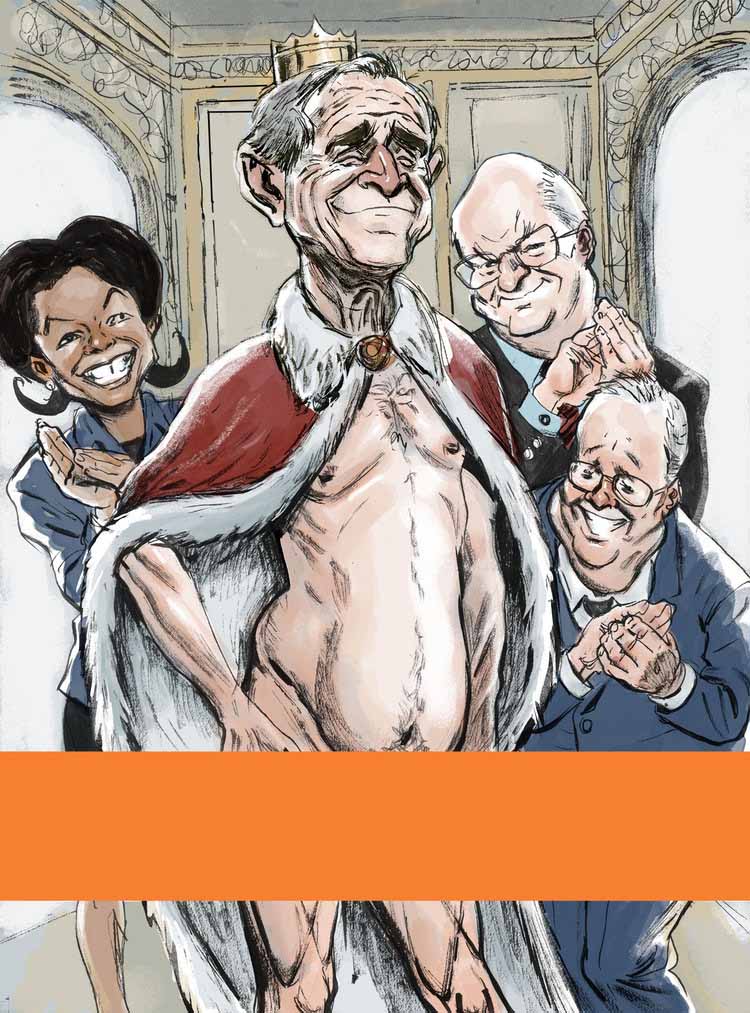

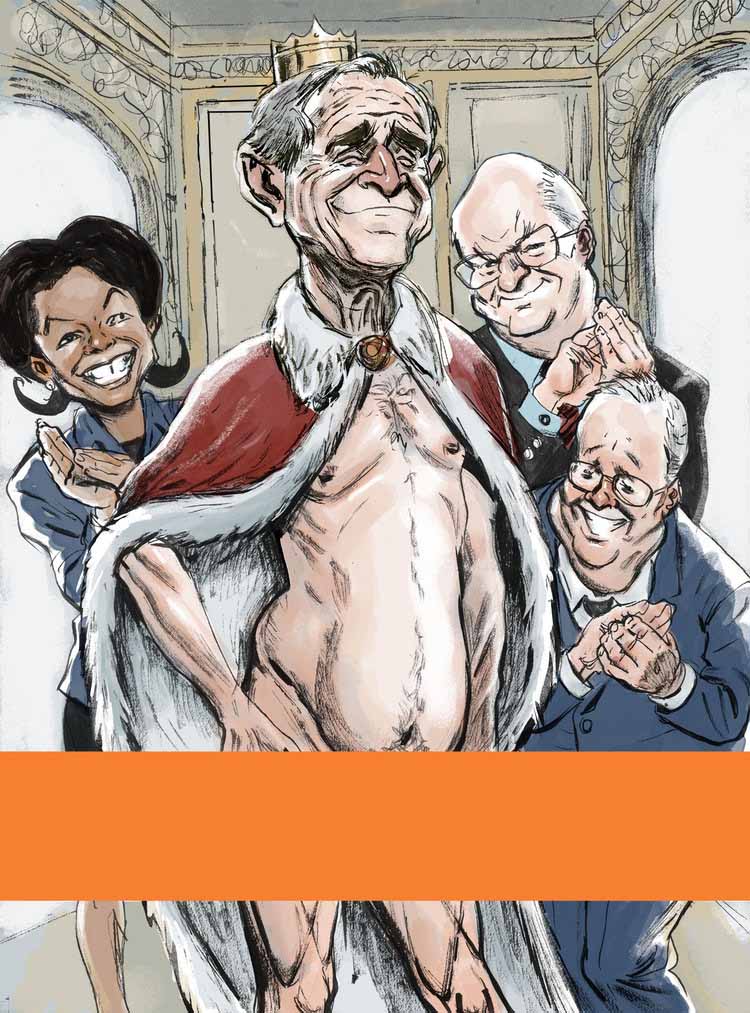

Bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, while deriding and humiliating so many around the world, America’s neoconservatives undressed the emperor. By taking off his clothes, they made his frailties visible for everyone to watch.

Inexplicable, under the light of common sense, the Bush team disassociated power from the international structures and norms that facilitated and legitimized its exercise. As a consequence, America moved from being the most successful hegemonic power ever to becoming a second-rate imperial power that proved incapable of prevailing in two peripheral wars. Bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, while deriding and humiliating so many around the world, America’s neoconservatives undressed the emperor. By taking off his clothes, they made his frailties visible for everyone to watch.

At the beginning of 2005, while reporting a Pew Research Center poll, The Economist stated that the prevailing anti-American sentiment around the world was greater and deeper than at any other moment in history. The BBC World Service and Global Poll Research Partners, meanwhile, conducted another global poll in which they asked, “How do you perceive the influence of the U.S. in the world?”. The populations of some of America’s traditional allies gave an adverse answer in the following percentages: Canada 60%; Mexico 57%; Germany 54%; Australia 52%; Brazil 51%; United Kingdom 50%. With such a negative perception among Washington’s closest allies, America’s credibility was in tatters.[2]

Is the liberal international order ending? what is next? dailysabah.com

While Bush’s presidency was reaching its end, Zbigniew Brzezinski wrote a pivotal book that asserted that the United States had lost much of its international standing. This felt, according to the book, particularly disturbing. Indeed, as a result of the combined impact of modern technology and global political awakening, that speeded up political history, what in the past took centuries to materialize now just took decades, whereas what before had taken decades, now could materialize in a single year. The primacy of any world power was thus faced with immense pressures of change, adaptation and fall. Brzezinski believed, however, that although America had deeply eroded its international standing, a second chance was still possible. This is because no other power could rival Washington’s role. However, recuperating the lost trust and legitimacy would be an arduous job, requiring years of sustained effort and true ability. The opportunity of this second chance should not be missed, he insisted, as there wouldn’t be a third one. [3]

A second chance

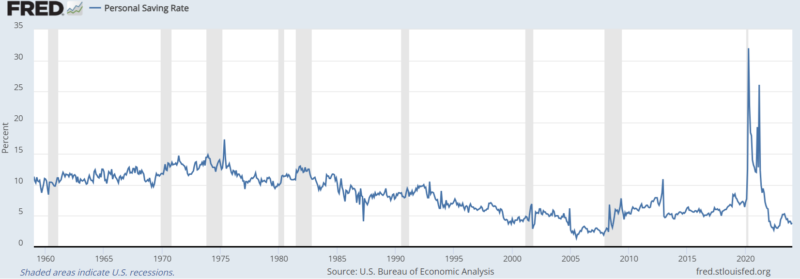

Barak Obama did certainly his best to recover the space that had been lost during the preceding eight years. That is, the U.S.’s leading role within a liberal internationalist structure. However, times had changed since his predecessor’s inauguration. In the first place, a massive financial crisis that had begun in America welcomed Obama, when he arrived at the White House. This had increased the international doubts about the trustiness of the country. In the second place, China’s economy and international position had taken a huge leap ahead during the previous eight years. Brzezinski’s notion that no other power could rival the United States was rapidly evolving. As a result, Obama was left facing a truly daunting challenge.

To rebuild Washington’s standing in the international scene, Obama’s administration embarked on a dual course of action. He followed, on the one hand, cooperative multilateralism and collective action. On the other hand, he prioritized the U.S.’ presence where it was most in need, avoiding unnecessary distractions as much as possible. Within the first of these aims, Obama seemed to have adhered to Richard Hass’ notion that power alone was simple potentiality, with the role of a successful foreign policy being that of transforming potentiality into real influence. Good evidence of this approach was provided through Washington’s role in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in relation to Iran, in the NATO summits, in the newly created G20, and in the summits of the Americas, among many other instances. By not becoming too overbearing, and by respecting other countries’ points of view, the Obama Administration played a leading influence within the context of collective action. Although theoretically being one among many, the United States always played the leading role.[4]

Within this context, Obama’s administration followed a coalition-building strategy. The Trans-Pacific Partnership represented the economic approach to the pivot and aimed at building an association covering forty per cent of the global economy. There, the United States would be the first among equals. As for the security approach to the pivot, the U.S. Navy repositioned its forces within the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans.

To prioritize America’s presence where it was most needed, Obama turned the attention to China and the Asia-Pacific. While America was focusing on the Middle East, China enjoyed a period of strategic opportunity. His administration’s “pivot to Asia” emerged as a result. This policy had the dual objective of building economic prosperity and security, within that region. Its intention was countering, through facts, the notion that America was losing its staying power in the Pacific. Within this context, Obama’s administration followed a coalition-building strategy. The Trans-Pacific Partnership represented the economic approach to the pivot and aimed at building an association covering forty per cent of the global economy. There, the United States would be the first among equals. As for the security approach to the pivot, the U.S. Navy repositioned its forces within the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans. From a roughly fifty-fifty correlation between the two oceans, sixty per cent of its fleet was moved to the Pacific. Meanwhile, the U.S. increased joint exercises and training with several countries of the region, while stationing 2,500 marines in Darwin, Australia. As a result of the pivot, many of China’s neighbours began to feel that there was a real alternative to this country’s overbearing assertiveness.[5]

Barak Obama was on a good track to consolidating the second chance that Brzezinski had alluded to. His foreign policy helped much in regaining international credibility and standing for his country, and the Bush years began to be seen as just a bump on the road of America’s foreign policy. Unfortunately, Donald Trump was the next President. And Trump coming just eight years after Bush, was more than what America’s allies could swallow.

Dog-eat-dog foreign policy

The Bush and Trump foreign policies could not be put on an equal footing, though. The abrasive arrogance of Bush’s neoconservatives, however distasteful, embodied a school of thought in matters of foreign policy. One, characterized by a merger between exalted visions of America’s exceptionalism and Wilsonianism. Francis Fukuyama defined it as Wilsionanism minus international institutions, whereas John Mearsheimer labelled it as Wilsionanism with teeth. Although overplaying conventional notions to the extreme, Bush’s foreign policy remained on track with a longstanding tradition. Much to the contrary, Trump’s foreign policy, according to Fareed Zakaria, was based on a more basic premise– The world was largely an uninteresting place, except for the fact that most countries just wanted to screw the United States. Trump believed that by stripping the global system of its ordering arrangements, a “dog eat dog” environment would emerge. One, in which his country would come up as the top dog. His foreign policy, thus, was but a reflection of gut feelings, sheer ignorance and prejudices.[6]

Trump derided multilateral cooperation and preferred a bilateral approach to foreign relations. One, in which America could exert its full power in a direct way, instead of letting it dilute by including others in the decision-making process. Within this context, the U.S.’ market leverage had to be used to its full extent, to corner others into complying with Washington’s positions. At the same time, he equated economy and national security and, as a consequence, was prone to “weaponize” economic policies. Moreover, he premised on the use of the American dollar as a bullying tool to be used to his country’s political advantage. Not only China but some of America’s main allies as well, were targeted within this approach. Dusting off Section 323 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, which allowed tariffs on national security grounds, Trump imposed penalizations in every direction. Some of the USA’s closest allies were badly affected as a result.

Given Trump’s contempt for cooperative multilateralism, but also aiming at erasing Obama’s legacy, an obsessive issue with him, he withdrew the U.S. from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, from the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in relation to Iran. He also withdrew his country from other multilateral institutions, such as the United Nations’ Human Rights Commission and, in the middle of the Covid 19 pandemic, from the World Health Organization. Trump threatened to cut funding to the U.N., waged a largely victorious campaign to sideline the International Criminal Court, and brought the World Trade Organization to a virtual standstill. Even more, he did not just walk away from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, in relation to Iran, but threatened its other signatories to impose sanctions on them if, on the basis of the agreement, they continued to trade with Iran.

Trump followed a transactional approach to foreign policy in which principles and allies mattered little, and where trade and money were prioritized over security considerations.

Trump followed a transactional approach to foreign policy in which principles and allies mattered little, and where trade and money were prioritized over security considerations. In 2019, he asked Japan to increase fourfold its annual contribution for the privilege of hosting 50,000 American troops in its territory, while requesting South Korea to pay 400 percent more for hosting American soldiers. This, amid China’s increasing assertiveness and North Korea’s continuous threats. In his relations with New Delhi, a fundamental U.S. ally within any containment strategy to China, he subordinated geostrategic considerations to trade. On the premise that India was limiting American manufacturers from access to its market, Trump threatened this proud nation with a trade war.[7]

Irritated because certain NATO member countries were not spending enough on their defence, Trump labelled some of Washington’s closest partners within the organization as “delinquents”. He also threatened to reduce the U.S.’ participation in NATO, calling it “obsolete”, while referring to Germany as a “captive of Russia”. At the same time, Trump abruptly cancelled a meeting with the Danish Prime Minister, because she was unwilling to discuss the sale of Greenland to the United States. This, notwithstanding the fact that this was something expressively forbidden by the 1975 Helsinki Final Act, represents the cornerstone of European stability. The European Union, in his view, was not a fundamental ally, but a competitor and an economic foe. Deliberately, Trump antagonized European governments, including that of London at the time, by cheering Brexit. Meanwhile, he imposed tariffs on steel and aluminium on many of its closest partners and humiliated Canada and Mexico by imposing upon them a tough renegotiation of NAFTA. One, whose ensuing accord did not bring significant changes. Moreover, he fractured the G7, a group integrated by Washington’s closest allies, leaving the United States standing alone on one side with the rest standing on the other.

In June 2018, Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, expressed his bewilderment at seeing that the rules-based international order was being challenged precisely by its main architect and guarantor– the United States. Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf summoned up all of this, by expressing that under Trump the U.S. had become a rogue superpower.

Unsurprisingly, thus, America’s closest allies reached the conclusion that they could no longer trust it. Several examples attested to this. In November 2017, Canberra’s White Paper on the security of Asia expressed uncertainty about America’s commitment to that continent. In April 2018, the United Kingdom, Germany and France issued an official statement expressing that they would forcefully defend their interests against the U.S.’ protectionism. On May 10, 2018, Angela Merkel stated in Aquisgran that the time in which Europe could trust America was over. On May 31, 2018, Justin Trudeau aired Canada’s affront at being considered a threat to the United States. In June 2018, Donald Tusk, President of the European Council, expressed his bewilderment at seeing that the rules-based international order was being challenged precisely by its main architect and guarantor– the United States. In November 2019, in an interview given to The Economist, Emmanuel Macron stated that the European countries could no longer rely on the United States, which had turned its back on them. Financial Times columnist Martin Wolf summoned up all of this, by expressing that under Trump the U.S. had become a rogue superpower.[8]

The return of liberal internationalism

Politically and geopolitically Biden rapidly went back to the old premises of liberal internationalism. Cooperative multilateralism and collective action were put back in place, and alliances became, once again, a fundamental part of America’s foreign policy.

As mentioned, George W. Bush followed a few years later by Donald Trump was more than what America’s allies could handle. Fortunately for that country, and for its allies, Trump failed to be re-elected in 2020, and Joe Biden came to power. True, the latter’s so-called foreign policy for the middle classes kept in place some of Trump’s international trade policies. However, politically and geopolitically he rapidly went back to the old premises of liberal internationalism. Cooperative multilateralism and collective action were put back in place, and alliances became, once again, a fundamental part of America’s foreign policy. Moreover, Biden forcefully addressed some of his country’s main economic deficiencies, which had become an important source of vulnerability in its rivalry with China. In sum, Biden strengthened the United States’ economy, its alliances, and its international standing.

Notwithstanding the fact that Biden had to fight inch by inch with a seemingly unconquerable opposition, while continuously negotiating with two reluctant senators from his own party, he was able to pass a group of transformational laws. Among them, are the Infrastructure Investment and Job Act, the CHIPS and Science Act and the Inflation Reduction Act. Together, these legislations allow for a government investment of a trillion dollars in the modernization of the country’s economy and its re-industrialization, including the consolidation of its technological leadership, the updating of its infrastructures and the reconversion of its energy matrix towards clean energy. Private investments derived from such laws would be gigantic, with the sole CHIPS Act having produced investment pledges of more than 100 billion dollars. This projects, vis-à-vis China’s competition, an image of strength and strategic purpose. Moreover, before foes and friends, these accomplishments prove that the U.S. can overcome its legislative gridlocks, in order to modernize its economy and its competitive standing.

Meanwhile, Washington’s alliances have significantly strengthened. In Europe, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Washington’s firm reaction to it had important consequences. While the former showed to its European allies that America’s leadership was still indispensable, the latter made clear that the U.S. had the determination and the capacity to exercise such leadership. Washington has indeed led in response to the invasion, in the articulation of the alliances and the revitalization of NATO, in sanctions on Russia, and in the organization of the help provided to Ukraine. It has also been Kyiv’s main source of support in military equipment and intelligence, deciding at each step of the road what kind of armament should be supplied to the Ukrainian forces. In short, before European allies that had doubted Washington’s commitments to its continent, and of the viability of NATO itself, America proved to be the indispensable superpower.

Meanwhile, American alliances in the Indo-Pacific have also been strengthened and expanded, with multiple initiatives emerging as a result. As the invasion of Ukraine made evident the return of geopolitics by the big door, increasing the fears of China’s threat to regional order, Washington has become for many the essential partner. America’s security umbrella has proved to be for them a fundamental tool in containing China’s increasing arrogance and disregard for international law and jurisprudence. Among the security mechanisms or initiatives created or reinforced under its stewardship are an energized Quad; the emergence of AUKUS; NATO’s approach to the Indo-Pacific region; the tripartite Camp David’s security agreement between Japan, South Korea and the U.S.; a revamped defence treaty with The Philippines; an increased military cooperation with Australia; and Hanoi’s growing strategic alignment with Washington. On the economic side, we find the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity and the freshly emerged Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment & India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor.

Enough would be enough

Although the Global South has proved to be particularly reluctant to fall back under the security leadership of the superpowers, Washington has undoubtedly become the indispensable partner for many in Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Thanks to Biden, the United States has repositioned itself on the cusp of a potent alliance system, regaining credibility and vitality. What would happen, thus, if he is defeated in the 2024 elections and Trump regains the White House? In 2007, Brzezinski believed, as mentioned, that although America had deeply eroded its international standing, a second chance was still possible. Actually, with Biden (and thanks in no small part to the Russian invasion and China’s pugnacity), the U.S. got an unexpected third chance. But definitively, enough would be enough. Moreover, during Trump’s first term in office, a professional civil service and an institutional contention wall (boosted by the so-called “adults in the room”), may have been able to keep at bay Trump’s worst excesses. According to The Economist, though, that wouldn’t be the case during a second term, where thousands of career public servants would be fired and substituted by MAGA followers. The deconstruction of the so-called “deep State” would be the aim to be attained, which would translate into getting rid of anyone who knows how to get the job done within the Federal Government. Hence, for America’s allies, Trump’s nightmarish first period would pale in relation to a second one. Trump followed four years later by Trump, no doubt about it, would shatter America’s trustiness, credibility, international standing, and its system of alliances. [9]

Notes:

[1] “Bracing for Trump 2.0”, Foreign Affairs, September 5, 2023

[2] The Economist, 19th February, 2005; Walt, Stephen M, Taming American Power, New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2005, p.72.

[3] Second Chance, New York: Basic Books, 2007, p. 191, 192, 206.

[4] Hass, Richard, “America and the Great Abdication”, The Atlantic, December 28, 2017.

[5] Campbell, Kurt, The Pivot, New York: Twelve, 2016, pp. 11-28.

[6] Steltzer, Irwin, Neoconservatism, London: Atlantic Books, 2004, pp. 3-28; Fukuyama, Francis, “After the Neoconservatives”, London: Profile Books, 2006, p. 41; Zakaria, Farid, “The Self-Destruction of American Power”, Foreign Affairs, July-August 2019.

[7] World Politics Review, “Trump works overtime to shake down alliances in Asia and appease North Korea”, October 14, 2019.

[8] White, Hugh, “Canberra voices fears”, The Strait Time, 25 November, 2017; Breuninger, Kevin, “Canada announces retaliatory tariffs”, CNBC, May 31, 2018; The Economist, “Emmanuel Macron warns Europe”, November 7th, 2019; Kishore Mahbubani, Has China Won? New York: Public Affairs, 2020, p. 56; Cooley, Alexander and Nexon, Daniel, Exit from Hegemony , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020, p. 70.

[9] The Economist, “Preparing the way: The alarming plans for Trump’s second term”, July 15th, 2023.

Feature Image Credit: livemint.com

Cartoon Credit: seltzercreativegroup.com

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Mission map for the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945. Scale is not consistent due to the curvature of the Earth. Angles and locations are approximate. Kokura was included as the original target for Aug. 9 but weather obscured visibility; Nagasaki was chosen instead. (Mr.98, Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

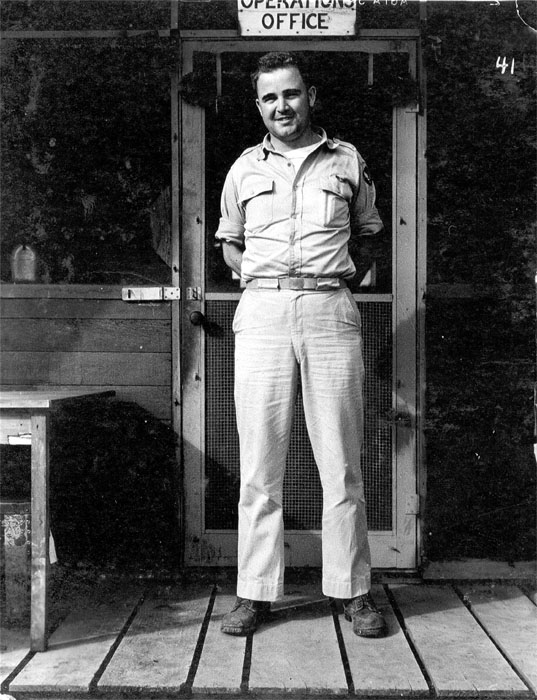

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)

Brigadier General Charles W. Sweeney, pilot of the aircraft that dropped the atomic bomb on Nagasaki. (Public domain, Wikimedia Commons)