Ben Norton reviews the interview given by the prominent French Scholar, Emmanuel Todd. The interview was in French and published in the major French newspaper ‘Le Figaro’. Emmanuel Todd argues the Ukraine proxy war is the start of WWIII, and is “existential” for both Russia and the US “imperial system”, which has restricted the sovereignty of Europe, making Brussels into Washington’s “protectorate”.

America is fragile. The resistance of the Russian economy is pushing the American imperial system toward the precipice. No one had expected that the Russian economy would hold up against the “economic power” of NATO. I believe that the Russians themselves did not anticipate it – Emmanuel Todd

A prominent French intellectual has written a book arguing that the United States is already waging World War Three against Russia and China.

He also warned that Europe has become a kind of imperial “protectorate”, which has little sovereignty and is essentially controlled by the US.

Emmanuel Todd is a widely respected anthropologist and historian in France.

In 2022, Todd published a book titled “The Third World War Has Started” (“La Troisième Guerre mondiale a commencé” in French). At the moment, it is only available in Japan.

But Todd outlined the main arguments he made in the book in a French-language interview with the major newspaper Le Figaro, conducted by the journalist Alexandre Devecchio.

According to Todd, the proxy war in Ukraine is “existential” not only for Russia, but also for the United States.

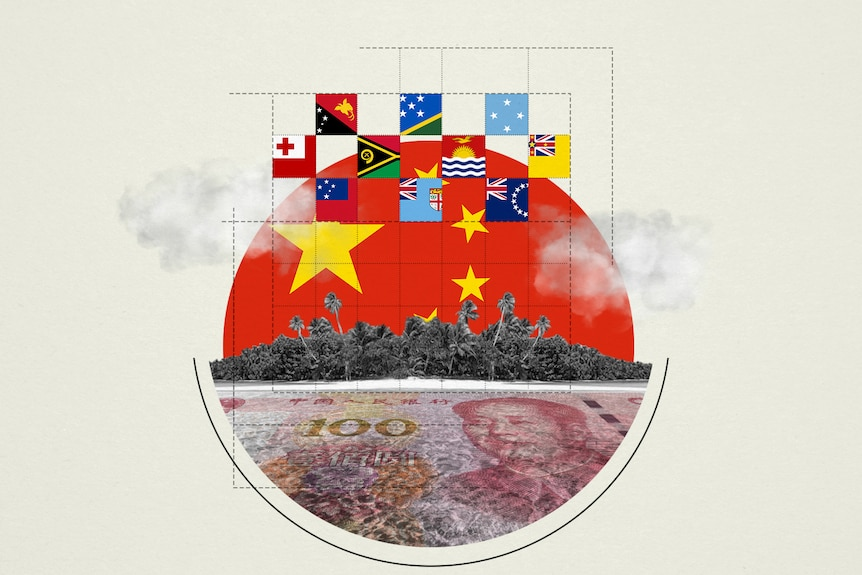

The US “imperial system” is weakening in much of the world, he observed, but this is leading Washington to “strengthen its hold on its initial protectorates”: Europe and Japan.

This means that “Germany and France had become minor partners in NATO”, Todd said, and NATO is really a “Washington-London-Warsaw-Kiev” bloc.

US and EU sanctions have failed to crush Russia, as Western capitals had hoped, he noted. This means that “the resistance of the Russian economy is pushing the American imperial system toward the precipice”, and “the American monetary and financial controls of the world would collapse”.

The French public intellectual pointed to UN votes concerning Russia, and cautioned that the West is out of touch with the rest of the world.

“Western newspapers are tragically funny. They don’t stop saying, ‘Russia is isolated, Russia is isolated’. But when we look at the votes of the United Nations, we see that 75% of the world does not follow the West, which then seems very small”, Todd observed.

He also criticized the GDP metrics used by Western neoclassical economists for downplaying the productive capacity of the Russian economy, while simultaneously exaggerating that of financialized neoliberal economies like in the United States.

In the Le Figaro interview, Todd argued (all emphasis added):

This is the reality, World War III has begun. It is true that it started ‘small’ and with two surprises. We went into this war with the idea that the Russian army was very powerful and that its economy was very weak.

It was thought that Ukraine was going to be crushed militarily and that Russia would be crushed economically by the West. But the reverse happened. Ukraine was not crushed militarily even if it lost 16% of its territory on that date; Russia was not crushed economically. As I speak to you, the ruble has gained 8% against the dollar and 18% against the euro since the day before the start of the war.

So there was a sort of misunderstanding. But it is obvious that the conflict, passing from a limited territorial war to a global economic confrontation, between the whole of the West on the one hand and Russia backed by China on the other hand, has become a war world. Even if military violence is low compared to that of previous world wars.

The newspaper asked Todd if he was exaggerating. He replied, “We still provide weapons. We kill Russians, even if we don’t expose ourselves. But it remains true that we Europeans are above all economically engaged. We also feel our true entry into war through the inflation and shortages”.

Todd understated his case. He didn’t mention the fact that, after the US sponsored the coup that overthrew Ukraine’s democratically elected government in 2014, setting off a civil war, the CIA and Pentagon immediately began training Ukrainian forces to fight Russia.

The New York Times has acknowledged that the CIA and special operations forces from numerous European countries are on the ground in Ukraine. And the CIA and a European NATO ally are even carrying out sabotage attacks inside Russian territory.

Nevertheless, in the interview, Todd continued:

Putin made a big mistake early on, which is of immense sociohistorical interest. Those who worked on Ukraine on the eve of the war considered the country not as a fledgling democracy, but as a society in decay and a ‘failed state’ in the making.

I think the Kremlin’s calculation was that this decaying society would crumble at the first shock, or even say ‘welcome Mom’ to holy Russia. But what we have discovered, on the contrary, is that a society in decomposition, if it is fed by external financial and military resources, can find in war a new type of balance, and even a horizon, a hope. The Russians could not have foreseen it. No one could.

Todd said he shares the view of Ukraine of US political scientist John Mearsheimer, a realist who has criticized Washington’s hawkish foreign policy.

Mearsheimer “told us that Ukraine, whose army had been taken over by NATO soldiers (American, British and Polish) since at least 2014, was therefore a de facto member of NATO, and that the Russians had announced that they would never tolerate a NATO member Ukraine,” Todd said.

For Russia, this is there a war that is “from their point of view defensive and preventative,” he conceded.

“Mearsheimer added that we would have no reason to rejoice in the eventual difficulties of the Russians because, since this is an existential question for them, the harder it was, the harder they would hit. The analysis seems to hold true.”

Germany and France had become minor partners in NATO and were not aware of what was going on in Ukraine on the military level. French and German naivety has been criticized because our governments did not believe in the possibility of a Russian invasion. True, but because they did not know that Americans, British and Poles could make Ukraine be able to wage a larger war. The fundamental axis of NATO now is Washington-London-Warsaw-Kiev.

However, Todd argued that Mearsheimer “does not go far enough” in his analysis. The US political scientist has overlooked how Washington has restricted the sovereignty of Berlin and Paris, Todd said:

Germany and France had become minor partners in NATO and were not aware of what was going on in Ukraine on the military level. French and German naivety has been criticized because our governments did not believe in the possibility of a Russian invasion. True, but because they did not know that Americans, British and Poles could make Ukraine be able to wage a larger war. The fundamental axis of NATO now is Washington-London-Warsaw-Kiev.

Mearsheimer, like a good American, overestimates his country. He considers that, if for the Russians the war in Ukraine is existential, for the Americans it is nothing but a power “game” among others. After Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan, one debacle more or less… What does it matter?

The basic axiom of American geopolitics is: ‘We can do whatever we want because we are sheltered, far away, between two oceans, nothing will ever happen to us’. Nothing would be existential for America. Insufficiency of analysis which today leads Biden to a series of reckless actions.

America is fragile. The resistance of the Russian economy is pushing the American imperial system toward the precipice. No one had expected that the Russian economy would hold up against the “economic power” of NATO. I believe that the Russians themselves did not anticipate it.

The French public intellectual went on in the interview to argue that, by resisting the full force of Western sanctions, Russia and China pose a threat to “the American monetary and financial controls of the world”.

This, in turn, challenges the US status as the issuer of the global reserve currency, which gives it the ability to maintain a “huge trade deficit”:

If the Russian economy resisted the sanctions indefinitely and managed to exhaust the European economy, while it itself remained backed by China, the American monetary and financial controls of the world would collapse, and with them the possibility for United States to fund its huge trade deficit for nothing.

This war has therefore become existential for the United States. No more than Russia, they cannot withdraw from the conflict, they cannot let go. This is why we are now in an endless war, in a confrontation whose outcome must be the collapse of one or the other.

Todd warned that, while the United States is weakening in much of the world, its “imperial system” is “strengthening its hold on its initial protectorates”: Europe and Japan.

He explained:

Everywhere we see the weakening of the United States, but not in Europe and Japan because one of the effects of the retraction of the imperial system is that the United States strengthens its hold on its initial protectorates.

If we read [Zbigniew] Brzezinski (The Grand Chessboard), we see that the American empire was formed at the end of the Second World War by the conquest of Germany and Japan, which are still protectorates today. As the American system shrinks, it weighs more and more heavily on the local elites of the protectorates (and I include all of Europe here).

The first to lose all national autonomy will be (or already are) the English and the Australians. The Internet has produced human interaction with the United States in the Anglosphere of such intensity that its academic, media and artistic elites are, so to speak, annexed. On the European continent we are somewhat protected by our national languages, but the fall in our autonomy is considerable, and rapid.

As an example of a moment in recent history when Europe was more independent, Todd pointed out, “Let us remember the war in Iraq, when Chirac, Schröder and Putin held joint press conferences against the war” – referring to the former leaders of France (Jacques Chirac) and Germany (Gerhard Schröder).

The interviewer at Le Figaro newspaper, Alexandre Devecchio, countered Todd asking, “Many observers point out that Russia has the GDP of Spain. Aren’t you overestimating its economic power and resilience?”

Todd criticized the overreliance on GDP as a metric, calling it a “fictional measure of production” that obscures the real productive forces in an economy:

War becomes a test of political economy, it is the great revealer. The GDP of Russia and Belarus represents 3.3% of Western GDP (the US, Anglosphere, Europe, Japan, South Korea), practically nothing. One can ask oneself how this insignificant GDP can cope and continue to produce missiles.

The reason is that GDP is a fictional measure of production. If we take away from the American GDP half of its overbilled health spending, then the “wealth produced” by the activity of its lawyers, by the most filled prisons in the world, then by an entire economy of ill-defined services, including the “production” of its 15 to 20 thousand economists with an average salary of 120,000 dollars, we realize that an important part of this GDP is water vapor.

War brings us back to the real economy, it allows us to understand what the real wealth of nations is, the capacity for production, and therefore the capacity for war.

Todd noted that Russia has shown “a real capacity to adapt”. He attributed this to the “very large role for the state” in the Russian economy, in contrast to the US neoliberal economic model:

If we come back to material variables, we see the Russian economy. In 2014, we put in place the first important sanctions against Russia, but then it increased its wheat production, which went from 40 to 90 million tons in 2020. Meanwhile, thanks to neoliberalism, American wheat production, between 1980 and 2020, went from 80 to 40 million tons.

…

Russia has therefore a real capacity to adapt. When we want to make fun of centralized economies, we emphasize their rigidity, and when we glorify capitalism, we praise its flexibility.

…

The Russian economy, for its part, has accepted the rules of operation of the market (it is even an obsession of Putin to preserve them), but with a very large role for the state, but it also derives its flexibility from training engineers, who allow the industrial and military adaptations.

This point is similar to what economist Michael Hudson has argued – that although Moscow’s economy is no longer socialist, like that of the Soviet Union was, the Russian Federation’s state-led industrial capitalism clashes with the financialized model of neoliberal capitalism that the United States has tried to impose on the world.

The Peninsula Foundation is happy to republish this article with the permission of the author, Ben Norton.

The article was published earlier in geopoliticaleconomy.com

Feature Image Credit: newstatesman.com

Portrait Sketch of Emmanuel Todd: Fabien Clairefond