Our ability to develop and prosper, both as a society and a nation, are wholly dependent on the smooth functioning of our democratic institutions and their ability to faithfully uphold the tenets laid down in our Constitution.

Our progress since Independence has not been without bumps along the road. Not only has the detritus of Partition haunted us, but we have also had to confront antagonistic neighbours intent on grabbing territory, creating divisions and curtailing our economic development and influence around the world. They have tried to do this by resorting to conventional operations, grey zone warfare, including using terrorist groups. In addition, we’ve had to overcome our internal troubles as well, what V.S. Naipaul referred to as a “million mutinies”, rebellions and insurgencies, for the most part, along our border regions. Undertaken by our disaffected citizens, in most cases with external support, aspiring to establish their own independent homelands because of ideological or religious motivations or out of a sense of frustration at being treated as second-class citizens within their own country.

The response of the State and Central Governments to these internal challenges has invariably been to initially attempt some sort of half-hearted political accommodation or initiative aimed at preserving the status quo and giving themselves political advantage. Once this fails, as it is bound to, the Central Armed Police Forces or the Army are brought in, depending on the levels of violence, to neutralise the insurgency and regain political and administrative control. This can take anywhere from a decade to three or more. The Mizoram Insurgency, for example, commenced in 1966 and was successfully terminated with the agreement being signed between opposing sides in 1986, while the Punjab Insurgency lasted from the mid-80s to the mid-90s, though there are efforts to restart it.

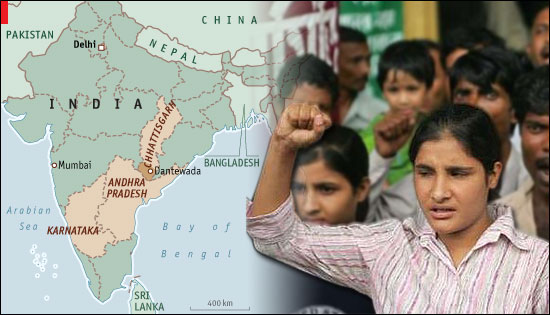

Unfettered exploitation of natural resources and minerals from those resource-rich regions by large corporations and their political acolytes has led to the displacement of tribals from their homelands and added to their economic woes. Given that the political, security and administrative establishments are wholly compromised and corrupt, the tribals have alleged that they have had little choice but to take up arms in an effort to break the nexus and get their rightful dues.

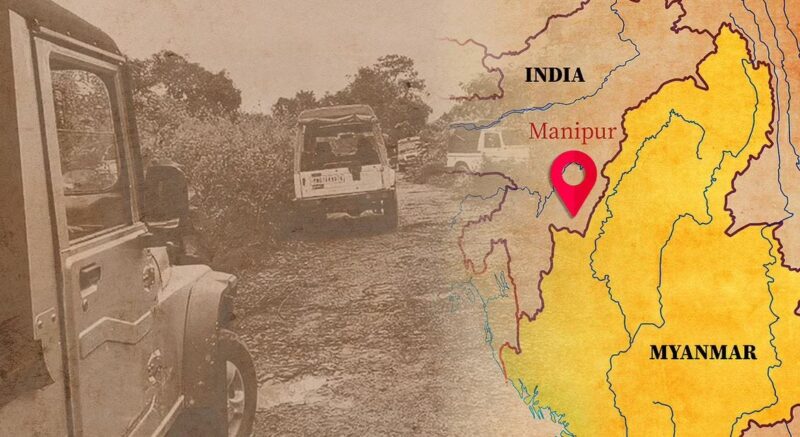

We’ve had similar problems in our North-eastern States of Assam, Nagaland, Manipur and Tripura, which continue to persist in fits and starts, aided, and abetted by China. We have also faced a long-running Maoist rebellion in our hinterland, organised and conducted by tribals from those regions. Unfettered exploitation of natural resources and minerals from those resource-rich regions by large corporations and their political acolytes has led to the displacement of tribals from their homelands and added to their economic woes. Given that the political, security and administrative establishments are wholly compromised and corrupt, the tribals have alleged that they have had little choice but to take up arms in an effort to break the nexus and get their rightful dues.

The issue we seem to have failed to comprehend is the transformation that has taken place in understanding what constitutes the basic elements of national security.

Fortunately, good sense prevailed within the political and security establishment, and the military, other than limited support in casualty evacuation and surveillance by the Air Force was completely kept out of ant-Maoist operations. The military’s job is not to protect marauding corporates but our sovereignty from the depredations of inimical elements, both internal and external. The dynamics of the Military’s involvement in countering the Maoist insurgency would have undoubtedly had serious repercussions within the military’s functioning, and over a period of time, would have adversely impacted our existing governance structures, much in the manner that some of our neighbours have been so affected. The issue we seem to have failed to comprehend is the transformation that has taken place in understanding what constitutes the basic elements of national security. Until the end of the Cold War and before the advent of globalisation, national security had purely military and economic connotations with the stress on territorial control. This was achieved by controlling the flow of information, goods and services and the movement of people through various means, including physical barriers. The advent of the Info-Tech revolution and the consequent move towards globalisation made it increasingly difficult for governments to control access to and the free flow of information, ideas, digital services, and finances.

As Professors, Wilson and Donan, note in their book, ‘Border Identities: Nation and State at the International Frontiers’ (UK, Cambridge: University Press, 1998), “International borders are becoming so porous that they no longer fulfil their historical role as barriers to the movement of goods, ideas and people and as markers of the extent of the power of the state.”

Perforce, governments the world over have been forced into the realisation, for many at great cost, that it has become impossible to lock up people or ideas and isolate them from the global discourse. Thus, in the context of the security of the state, more than just ensuring territorial integrity, it is the security of the people through sustainable human development that is non-negotiable. We are today at a stage where, while traditional physical threats continue to pose serious challenges, especially from China and Pakistan, it is the non-military threats that are more dominant. These arise, on one side, from the host of cross-border insurgencies that afflict us because of ethnic, ideological, economic or religious conflicts, and on the other side, because of policies that emanate from politics of exclusion and economic exploitation. In both cases endemic corruption due to the nexus between the political-bureaucracy-security establishment and criminal elements involved in the smuggling of drugs and weapons and human trafficking remains the common thread. As a result, we not only face the threat of violence but also have to confront the increasing spread of religious radicalization.

For example, in the Northeast, as my colleagues, Lt Gen J S Bajwa (Retd), Maj Gen N G George (Retd) and I, have pointed out in our paper, ‘Makeover of Rainbow Country: Border Security and connecting the Northeast’ (Manekshaw Paper No 62, Centre for Land Warfare Studies, 2016), “we are faced with a trans-border insurgency affecting our states that has metamorphosed into a serious law and order issue due to trans-national criminal syndicates having established linkages with armed gangs that are opposed to the existing political status-quo. This has also been accentuated with these groups being used by China and Pakistan for meeting their own nefarious designs…. Criminal syndicates have extended their reach to include complete control and dominance over all smuggling activities, be it of small arms, psychotropic drugs, livestock, or human trafficking. This economic clout has enabled them to subvert elements within the political parties, the bureaucracy, and the security establishment….”. Thus, it appears that the defining characteristic of on-going insurgencies is that they are nothing more than “businesses”, using all means at their disposal to make a profit. Thus, we see that has been that they have never crossed the threshold of violence or mass mobilisation that would lead to the next logical phase; from insurgency to civil war, where insurgent forces take on the military in conventional operations. These regions are further adversely impacted by poor governance, ineffective policing, agonisingly slow judicial processes, and unchecked criminal activity. The ability of the local populace to oppose the injustices heaped on them has been very subtly neutralised using the Security Forces and Police with wide ranging powers, including in some regions the use of AFSPA, to maintain the status quo. Our ability to develop and prosper, both as a society and a nation, are wholly dependent on the smooth functioning of our democratic institutions and their ability to faithfully uphold the tenets laid down in our Constitution. This is not feasible without sustained focus on providing high quality of universal education, emphasis on social justice and inclusion and an unvarying commitment to ensuring accountability and the rule of law. Focus on infrastructure development in border areas as well as ensuring free and fair elections, greater accountability and breaking the existing nexus between criminal groups and the local political and administrative establishment and unethical corporate houses. Clearly, all stakeholders have to accept that resorting to the use of force in order to ensure a stable security environment is an unviable option with very limited positives.

The ability of the local populace to oppose the injustices heaped on them has been very subtly neutralised using the Security Forces and Police with wide ranging powers, including in some regions the use of AFSPA, to maintain the status quo.

Finally, a word with regard to countering terrorist actions such as the one that targeted Mumbai on 26 November 2008. Much has changed since then with our major cites becoming far less vulnerable thanks to a quantum enhancement of the coastal surveillance infrastructure as well as better coordination, integration and demarcation of responsibilities amongst the stakeholders such as the Indian Navy, Coast Guard, local police and the intelligence agencies. In addition, the establishment of integrated National Security Guards (NSG) hubs in Mumbai and other metropolises ensures much speedier response as well as better coordination with local police and their Special Weapons and Tactics (SWAT) Teams. Efforts have also been directed to enhancing training of personnel and upgrading technical capabilities.

Unfortunately, politics has played a major spoilsport and two important initiatives planned in the aftermath of the Mumbai attack, the establishment of the National Counter Terrorism Centre (NCTC) and its intelligence data exchange architecture (NATGRID) have not fully fructified. There can be little doubt that these initiatives, if pushed through as visualised, would have been of immense utility in ensuring our ability to prevent and respond to terror threats in a timely and effective manner. To conclude, it would be fair to suggest that we face an extremely difficult and challenging internal security environment that is deeply entwined in, and impacted by, our external threat perceptions. Of necessity, we must adopt robust policies, with the requisite capabilities, to be able to respond appropriately so as to be perceived as a ‘hard state’ by our neighbours. This would give us the necessary space andenvironment to push through policies focussing on sustainable human development, which is the only feasible option to ameliorate our internal security challenges.

Feature Image Credit: the diplomat