Humanity is in the midst of a global upheaval, on a scale unseen in 500 years: namely, the relative decline of Europe and the United States, the rise of China and the Global South, and the resulting revolutionary transformation of the international landscape. Although the era of Western global dominance is often said to have lasted five centuries, precisely speaking this is an overstatement. In reality, Europe and the United States have occupied their positions as world hegemons for closer to 200 years, after reaching their initial stages of industrialisation. The first industrial revolution was a turning point in world history, significantly impacting the relationship between the West and the rest of the world. Today, the era of Western hegemony has run its course and a new world order is emerging, with China playing a major role in this development. This article explores how we arrived at the current global conjuncture examining the different stages in the relationship between China and the West.

Stage I: A Shifting Balance Between China and the West

The first encounter between China and Europe dates back to the era of naval exploration of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, during which the Chinese navigator and diplomat Zheng He (1371–1433) embarked on his Voyages Down the Western Seas (郑和下西洋, Zhèng Hé xià xīyáng) (1405–1433), followed by the Portuguese and Spanish naval expeditions to Asia. From then on, China has established direct contact with Europe through ocean passages.

During this period China was ruled by the Ming dynasty (1388–1644), which adopted a worldview guided by the concept of tianxia (天下, tiānxià, ‘all under heaven’). This belief system generally categorised humanity into two major civilisations: the Chinese who worshipped heaven, or the sky, and the West which, broadly, worshipped gods in a monotheistic sense. It is important to note that, in this era, the Chinese had a broad conception of the West, considering it to encompass all the regions which expanded northwestward from Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean Sea and then to the Atlantic coast, rather than the contemporary notion which is generally limited to of the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Europe. On the other hand, Chinese civilisation spread to the southeast, from the reaches of the Yellow River to the Yangtze River Basin onward to the coast. The two civilisations would meet at the confluence of the Indian and Pacific Oceans, from which point there has been a complete world history to speak of. At the same time, however, tianxia put forward a universalist conception of the world, in which China and the West were considered to share the same ‘world island’. Separated by the ‘Onion Mountains’ (the Pamir Mountains of Central Asia), each civilisation was thought to have its own history, though there was not yet a unified world history, and each maintained, based on their own knowledge, the tianxia order at their respective ends of the world island.

Although the Ming dynasty discontinued its sea voyages after Zheng He’s seventh mission in 1433, some islands in the South Seas (南洋, nányáng, roughly corresponding to contemporary Southeast Asia) became incorporated into the imperial Chinese tributary system (朝贡, cháogòng). This constituted a major change in the tianxia order, compared with the prior Han (202 BCE–CE 9, 25–220 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) dynasties in which tribute was mainly received from states of the Western Regions (西域, xīyù, roughly corresponding to contemporary Central Asia). More importantly, this southeastward expansion opened a road into the seas for China, as Chinese people of the southeast coast migrated to the South Seas, and with them goods such as silk, porcelain, and tea entered the maritime trade system. Compared with the prosperous Tang and Song (960–1279) periods, overseas trade expanded, with the Jiangnan (江南, jiāngnán, ‘south of the Yangtze River’) economy, which was largely centred on exports, being particularly dynamic; consequently, industrialisation accelerated and China, for the first time, became the ‘factory of the world’.

European nations did not have the upper hand in their trade with China, however, they offset their deficit with the silver that they mined in the newly conquered Americas. This silver flowed into China in large quantities and became a major trading currency, leading to the globalisation of silver. Meanwhile, the introduction of corn and sweet potato seeds, native to the Americas, to China contributed to the rapid growth of the nation’s population due to the suitability of these crops to harsh conditions.

However, China’s involvement in shaping a maritime-linked world order also brought about unexpected problems for the country; namely, an imbalance between its economy, which penetrated the maritime system, and its political and military institutions, which remained continental. This contradiction between the land and the sea produced significant tensions within China, eventually leading to the demise of the Ming dynasty. Border conflicts in the north and northeast required significant financial resources, however most of China’s wealth at that time came from maritime trade and was concentrated in the southeast. Consequently, education thrived in this coastal region, resulting in scholar-officials (士大夫, shìdàfū) from the southeast coming to dominate China’s political processes and prevent tax reforms to better distribute wealth – instead, the traditional tax system was strengthened, imposing larger burdens on the peasantry. These tensions would eventually come to a head; taxation weighed particularly heavily on northern peasants who mainly lived off farming, leading to their displacement and becoming migrants who eventually overthrew the Ming regime. At the same time, military resources in the north were insufficient, leading to the growing influence of Qing rebel forces in the northeast and their opportunistic advances to the south, culminating in the establishment of the Qing dynasty’s (1636–1912) rule over the entire country.

The Qing dynasty originated among the Manchu people of northeast China, who had agricultural and nomadic cultural roots. As Qing forces marched southwards and founded their empire, they made great efforts to establish control over the regions flanking China from the west and north, an arc extending from the Mongolian Plateau to the Tianshan Mountains and to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. For thousands of years, these northwest regions were a source of political instability, with successive dynasties trying and failing to unify the whole of China. By integrating these areas into the Chinese state, the Qing dynasty was thus able to achieve this historic political aim of unification. This domestic integration also had an impact on China’s international position, with Russia now becoming the country’s most important neighbour as the overland Silk Road was rerouted northwards, via the Mongolian steppe, through Russia to northern Europe.

By the mid-to-late eighteenth century, these two ‘arcs’ of development, on the land and sea respectively, held equal weight but differing significance for China: the land provided security, while the seas were the source of vitality. However, both the land and sea developments contained contradictory dynamics: the regions of the northwestern steppe were not very stable internally while relations with neighbouring Russia and the Islamic world remained stable, on the other hand, the southeastern seas were stable internally but introduced new challenges for China in the form of relations with Europe and the United States. These land-sea dynamics have historically presented China with unique trade-offs and, to this day, they remain a fundamental strategic issue.

In contrast, European countries benefited more from direct trade with China, and rose to a dominant position within the new global order. During the sixteenth century, under the increasingly decadent Roman Catholic Church, ethnic nationalism brewed up in Europe, culminating in Martin Luther’s Reformation in Germany. Subsequently, Europe entered an era of nation-state building known as the early modern period, characterised by the break-up of the authority of the Roman Catholic Church and the establishment of the sovereignty of secular monarchies, which overcame some of the hierarchies and divisions created by the feudal lords and made all subjects equal under the king’s law. The first country to achieve this was England, where Henry VIII banned the Church of England from paying annual tribute to the Papacy in 1533 and passed the Act of Supremacy the following year, establishing the king as the supreme head of the English Church which was made the state religion. This is why England is recognised as the first modern nation, while the constitutional changes were secondary.

The Roman Catholic Church, facing a ruling crisis, sought to open up new pastoral avenues, and began to preach outside of Europe through the voyages of ‘discovery’. Christianity gradually became a world religion, one of the most important developments in the last five centuries, with missionaries finally making their way to China, after many twists and turns, in the late sixteenth century.

The Christian missionaries had prepared to spread their message of truth to the Chinese, who they had expected to be ‘barbarians’. However, to their surprise, they discovered that China was a powerful civilisation with a sophisticated governance system and religious traditions. Although not believing in the personal gods of the missionaries, the Chinese people had a system of moral principles, a highly developed economy, and an established order. This inspired some missionaries to develop a serious appreciation for China, including translating Chinese classics and sending the texts back to Europe, where they would have a notable impact on the Enlightenment in Paris.

During the Enlightenment, Western philosophers developed ideas of humanism and rationalism, including notions that human beings are the subject and a ‘creator’ does not exist; humans should seek their own happiness instead of trying to ascend to the kingdom of God; humans can have sound moral beliefs and relations without relying on religion; the state can establish order without relying on religion; direct rule by the king over all subjects is the best political system, and so on. It is important to note, however, that these Enlightenment ideals, which are said to have formed the basis for Western modernity, had been common knowledge in China for thousands of years. As such, the flow of Chinese ideas and teachings to the West through Christian missionaries can be considered an important, if not the only, influence in the development of Western modernisation. Of course, Western countries have been the main drivers of global modernisation over the last two centuries, but the modernity that it advocates has long been embedded in other cultures, including China. It is necessary to recognise and affirm this fact to understand the evolution of the world today.

In short, during the first stage of world history, which spanned more than 300 years from the early-to-mid fifteenth century to the mid-to-late eighteenth century, an integrated world system began to form, with both China and the West adjusting, changing, and benefiting in their interactions. From the Chinese perspective, this world order was largely fair.

Stage II: Reversals of Fortunes Between China and the West

In the mid-to-late eighteenth century, Western countries utilised their higher levels of industrialisation to secure decisive military superiority, which they abused to conquer and colonise nearly the entire Global South. This brought the world closer together than ever before, but in a union that was unjust and, therefore, unsustainable.

Among the Western countries, England was the first to achieve an advanced stage of industrialisation, for which there was a special reason: colonisation. The British Empire appropriated massive amounts of wealth from its colonies, which also served as captive markets for British manufactures. This wealth and market demand, along with England’s relatively small population, drove scientific and technological development, and ultimately industrialisation based on the mining of fossil fuels (namely, coal), and the production of steel and machinery. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, England would become the wealthiest and most powerful country in the world, with its wealth spreading to Western Europe and its colonial settlements such as the United States and Australia. The thriving European powers violently conquered and colonised the outside world through military force including most of Africa, Asia, and the Americas, eventually reaching China’s doorstep in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. In the preceding centuries of peaceful trading with China, the Western powers accumulated a large trade deficit, which they now sought to balance through the opium trade. However, due to the severe social consequences of this drug trade, China outlawed the importation of opium in 1800; in response, the Western powers launched two wars against China – the First Opium War (1839–1842) and the Second Opium War (1856–1860) – to violently open the country’s markets up. After China was defeated, various Western countries, including England, France, Germany, and the United States, forced China to sign unequal treaties granting these nations trade concessions and territories, including Hong Kong. As a result, the tianxia order began to crumble and China entered a period referred to as the ‘century of humiliation’ (百年国耻, bǎinián guóchǐ).

China’s setback was rooted in the long-standing imbalance between its marine-oriented economy and continental military-political system. First, China’s market relied heavily on foreign trade, but the Qing government failed to develop a sovereign monetary policy, resulting in the trade flow being constantly controlled by foreign powers. Silver from abroad became China’s de facto currency and, with the government unable to exercise effective supervision, the country lost monetary sovereignty and was vulnerable to the fluctuations of silver supplies, destabilising the economy. Second, China’s natural resources were over-exploited to produce large amounts of exports; as a result, the country’s ecological environment was severely damaged. Constrained by both market and resource limitations, China’s endogenous growth hit a chokepoint, as productivity plateaued, employment declined, and surplus populations became displaced, leading to a series of major rebellions in the early-to-mid nineteenth century. It was in this context that the West showed up at China’s doorstep.

Under the pressure of both domestic problems and external aggression, China embarked on the path of ‘learning from the outside world to defend against foreign intervention’ (师夷长技以制夷, shī yí zhǎng jì yǐ zhì yí), which has been fundamental theme of Chinese history over the past century or so. This formulation, despite having been ridiculed by many since the 1980s following the initiation of China’s economic reforms, epitomises the country’s strategy. On the one hand, China has closely studied the key drivers of Western power, namely industrial production, technological development, economic organisation, and military capability, as well as methods for social mobilisation based on the nation-state. On the other hand, China has sought to learn from other countries for the purpose of advancing its development, securing its independence, and building upon its own heritage.

Until the mid-twentieth century, however, this path did not yield significant changes for China, fundamentally due to its inadequate state capacity, which deteriorated even further after the Qing dynasty fell in 1911. In fact, several initiatives undertaken in the late Qing period to strengthen the state, generated new problems in turn; for example, the ‘New Army’ (新军, xīnjūn) which was established in the late-nineteenth century in an effort to modernise China’s military would turn into a secessionist force. Meanwhile, theories of development advocated by scholar-officials in this period, such as the concept of ‘national salvation through industry’ (实业救国, shíyè jiùguó), were impossible to implement due to the state’s inability to provide institutional support. As such, trade remained China’s fastest growing economic sector, which, despite bringing short-term economic benefits, resulted in China becoming further subordinated to the West.

However, by the time of the Second World War, which was preceded by China’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1937–1945), the country’s international position began to improve, while the West experienced a relative decline. The Second World War and anti-colonial struggles for national liberation dealt a crushing blow to the old imperialist order, as the Western powers were forced to retreat, initiating a decline as they were no longer able to reap colonial dividends. Countries across Asia, Africa, and Latin America, including China, won their independence; meanwhile, the Soviet Union, stretching across Eurasia, emerged as a significant rival to the West. Amid these global convulsions, China’s weight on the international stage dramatically increased and it became an important force.

In this global context, China began its journey toward national rejuvenation, with two main priorities. The first priority was political; emulating the Soviet Union, China’s Nationalist and the Communist parties established a strong state, which had been the cornerstone of Western economic development, while the lack of state organisation and mobilisation capacity was the greatest weakness of the Qing dynasty in the face of Western powers. The second priority was industrialisation, which advanced in a step-by-step manner in three phrases.

The first breakthrough in industrialisation took place after the Chinese Revolution in 1949 and was made possible by the help of the Soviet Union, which exported a complete basic industrial system to China. Although this system had serious limitations, which came to a head by the 1970s and 1980s, it allowed China to develop a comprehensive understanding of the systematic nature of industry, especially the underlying structure of industrialisation, that is, heavy industry.

The second breakthrough in industrialisation came after China established diplomatic relations with the United States in the 1970s and began to import technologies from the US and European countries. During this phase, China focused on the development of its southeast coast, a region which had a longstanding history of rural commerce and industry. With the support of machinery and knowledge gained during the first round of industrialisation, the consumer goods sector in the southeast coastal areas was able to develop rapidly at the township level, the level of government which had the most flexibility. By absorbing a large amount of workers, the labour-intensive industrial system significantly improved livelihood for the people.

The third breakthrough in industrialisation, beginning at the turn of the century, was driven by the traditional emphasis for a strong state and a desire to continue the revolution, saw the government devote its capacity to building infrastructure and steering industrial development. As a result, China experienced continuous growth in industrial output and kept moving upwards along the industrial chain, creating the largest and most comprehensive manufacturing sector in the world. The global economic landscape thus changed dramatically.

Today, China is in the midst of its fourth breakthrough in industrialisation, which revolves around the application of information technology to industry. In the current period, the United States is worried about being overtaken by China, which has prompted a fundamental change in bilateral relations and ushered in an era of global change.

In short, at the heart of the second stage of world history were the shifting dynamics between China and the West. For more than 100 years since the early nineteenth century, the Western powers were on the upswing while China experienced a downturn; since the Second World War, however, the trends have reversed, with China on the rise and the West declining. Now it appears that the critical point in this relationship is approaching, where the two sides will reach equivalent positions, exhausting the limits of the old world order.

Stage III: The Decline of the US-Led Order

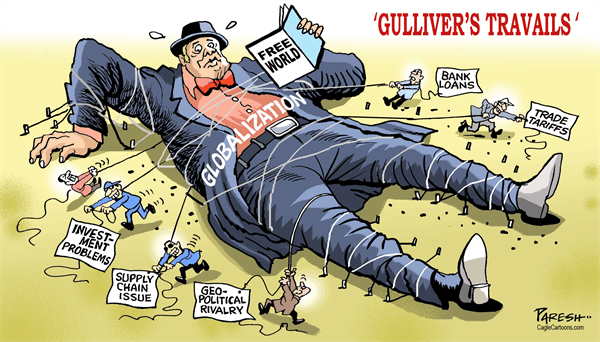

In the wake of China’s rise, the old, Western-dominated world order has been overwhelmed, however, the real trigger for its collapse is the instability resulting from the fact that the United States has been unable to secure the unipolar global dominance which it pursued after the end of the Cold War.

Historically, the Roman empire could not reach India, let alone venture beyond the Onion Mountains; in the other direction, the Han and Tang dynasties could have hardly maintained their power even if they had managed to cross this range. The structural equilibrium for the world is for nations to stay in balance, rather than be ruled by a single centre.

Even the immense technological advances in transportation and warfare have been unable to change this iron law. Prior to the Second World War, the Western powers had penetrated nearly all corners of the world; despite their competing interests and the force needed to maintain their colonies, this system of rule was, in a way, more stable than the current order by distributing power more broadly across the several countries. Meanwhile, in the postwar period, the Soviet Union and the West formed opposing Cold War blocs, with each camp having its own scope of influence and balanced, to an extent, by the other.

In contrast, following the end of the Cold War, the United States became the sole superpower, dominating the entire world. The United States, as the most recently established Western country, the last ‘New World’ to be ‘discovered’ by the Europeans, and the most populous of these powers, was destined to be the final chapter in the West’s efforts to dominate the world. The United States confidently announced that their victory over the Soviet Union constituted ‘the end of history’. However, ambition cannot bypass the hard constraint of reality. Under the sole domination of the United States, the world order immediately became unstable and fragmented; the so-called Pax Americana was too short-lived to be written into the pages of history. After the brief ‘end of history’ euphoria under the Clinton and Bush administrations, the Obama era saw the United States initiate a ‘strategic contraction’, seeking to unload its burdens of global rule one after another.

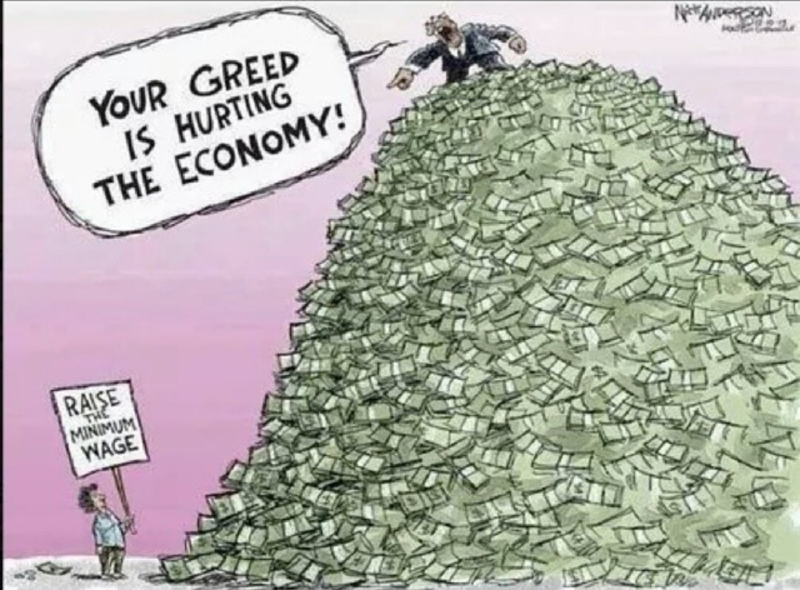

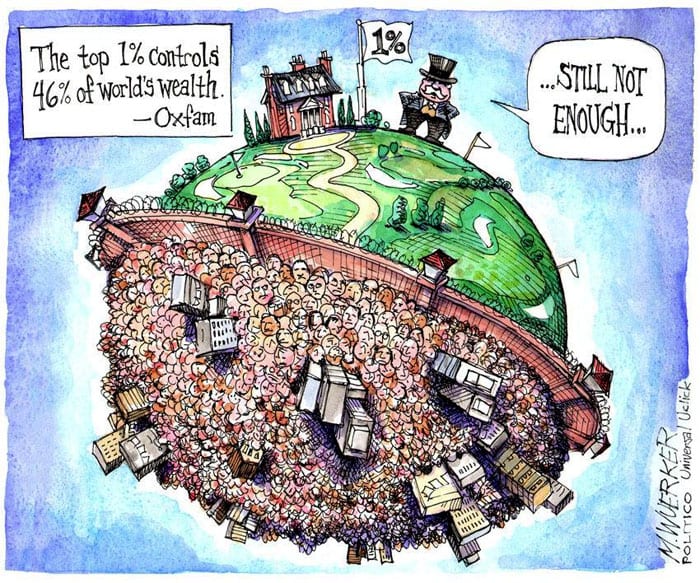

In addition to external costs, Washington’s fleeting pursuit of global hegemony also induced internal strains. Although the United States reaped many dividends from its imperial rule by developing a financial system in which capital could be globally allocated, this came with a cost; as a Chinese saying goes, ‘a blessing might be a misfortune in disguise’ (福兮祸所依, fú xī huò suǒ yī). The boom of the US financial sector, along with the volatile speculation that feeds off it, has caused the country to become deindustrialised, with the livelihoods of the working and middle classes bearing the brunt. Due to the self-protective measures of emerging countries such as China, it was impossible for this financial system to fully extract sufficient external gains to cover the domestic losses suffered by the popular classes due to deindustrialisation. Consequently, the US has developed extreme levels of income inequality, and become sharply polarised, with increasing division and antagonism between different classes and social groups.

Deindustrialisation is at the root of the US crisis. Western superpowers were able to tyrannise the world during the nineteenth century, including their bullying of China, mainly due to their industrial superiority, which allowed them produce the most powerful ships and cannons; deindustrialisation causes the supply of those ‘ships and cannons’ to become inadequate. Even the US military-industrial system has become fragmentary and excessively costly due to the decline of supporting industries. The US elite realises the gravity of this problem, but successive administrations have struggled to address the issue; Obama called for reindustrialisation but made no progress due to the deep impasse between Republicans and Democrats, a dynamic that inhibits effective government action, which Francis Fukuyama termed the ‘vetocracy’; Trump followed this up with the timely slogan ‘Make America Great Again’, promising to make the US the world’s strongest industrial power once more; and this intention can also be seen in the incumbent Biden administration’s push for the enactment of the CHIPS and Science Act and other initiatives aimed at boosting domestic industrial development. However, as long as US finance capital can continue to take advantage of the global system to obtain high profits abroad, it cannot possibly return to domestic US industry and infrastructure. The United States would have to break the power of the financial magnates in order to revive its industry, but how could this even be possible?

In contrast to the deindustrialisation which has taken place in the United States, China is steadily advancing through its fourth breakthrough of industrialisation and rising towards the top of global manufacturing, relying on the solid foundation of a complete industrial chain. Fearing that they will be surpassed in terms of ‘hard power’, the US elite has declared China to be a ‘competitor’ and the nature of relations between the two countries has fundamentally changed.

The US elite have long referred to their country as the ‘City upon a Hill’, a Christian notion by which it is meant that the United States holds an exceptional status in the world and is a ‘beacon’ for other nations to follow. This deep-seated belief of superiority means that Washington cannot accept the ascendance of other nations or civilisations, such as China, which has been following its own path for thousands of years. China’s economic rise and, consequently, its growing influence in reshaping the US-led global order is nothing more than the world returning to a more balanced state; however, this is sacrilegious to Washington, comparable to the rejection of religious conversion for missionaries. It is clear that the US elite have exhausted their goodwill for China, are united in pursuing a hostile strategy against it, and will use all means to disrupt China’s development and influence on the world stage. Washington’s aggressive approach has, in turn, hardened the resolve of China to extricate itself from the confines of the US-led global system. Pax Americana will only allow China to develop in a manner which is subordinated to the rule of the United States, and so China has no choice but to take a new path and work to establish a new international order. This struggle between the United States and China is certain to dominate world headlines for the foreseeable future.

Nevertheless, there are several factors which decrease the likelihood that the struggle will develop in a catastrophic manner. First, the two countries are geographically separated by the Pacific ocean; and, second, although the United States is a maritime nation adept at offshore balancing, it is much less capable of launching land-based incursions, particularly against a country such as China which is a composite land-sea power with enormous strategic depth. As a result, US efforts to launch a full-scale war against China would be nonviable; even if Washington instigated a naval war in the Western Pacific, the odds would not be in its favour. On top of these two considerations, the United States is, in essence, a ‘commercial republic’ (the initial definition given for the country by one of its Founding Fathers, Alexander Hamilton), meaning that its actions are fundamentally based on cost-benefit calculations; China, on the contrary, is highly experienced in dealing with aggressive external forces.Altogether, these factors all but guarantee that a full-frontal war between the two countries can be entirely avoided.

In this regard, the shifting positions of China and the United States vary greatly from similar dynamics in the past, such as the evolving hegemony on the European continent in recent centuries. In the latter context, the narrow confines of Europe cannot allow for multiple major powers, whereas the vast Pacific Ocean certainly can. This situation constitutes the bottom line of the relationship between the two countries. Therefore, while China and the United States will compete on all fronts, as long as China continues to increase its economic and military strength and clearly demonstrates its willingness to use that power, the United States will retreat in the same rational manner as its former suzerain, Britain, did. Once the United States withdraws from East Asia and the Western Pacific, a new world order will begin to take shape.

Over the past few years, China’s efforts in this respect have paid off, causing some within the United States to recognise China’s power and determination, and adjust their strategy accordingly, pressuring allied countries to bear greater costs to uphold the Western-led order. Despite the posturing of the Western countries, there is, in fact, no such ‘alliance of democracies’; the US has always based its alliance system on common interests, of which the most important is to work together, not to advance any high-minded ideal, but to bleed other countries dry. Once these countries can no longer secure external profits together, they will have to compete with each other and their alliance system will promptly break up. In such a situation, the Western countries would return to a state similar to the period before the Second World War; fighting each other for survival rather than to carve the world into colonies. This battle of nations, although not necessarily through hot war, could cause the Western countries to backslide to their early modern state.

The willingness of the United States to do anything in its pursuit of profit, has led to the rapid crumbling of its value system. Since former President Woodrow Wilson led the country to its position as the leader of the world system, values have been at the core of the US appeal. At that time, Wilson held sway with many Chinese intellectuals, though disillusion soon followed; meanwhile, today, the myth of the ‘American dream’ and universal values of the United States remains charismatic to a considerable proportion of Chinese elites, however, the experience of the Trump presidency has torn the mask off these purported values. The United States has openly returned to the vulgarity and brutality of colonial conquest and westward expansion.

In addition, the current generation of Western elites suffers from a deficit in its capacity for strategic thinking. Many of the leading strategists and tacticians of the Cold War have now died, and amid hubris and dominance of the two decade ‘end of history’ era, the United States and European countries did not really produce a new generation of sharp intellectual figures. Consequently, in the face of their current dilemmas, the best that this generation of elites can offer is nothing more than repurposing old solutions and returning to the vulgarity of the colonial period.

This kind of vulgarity may be shocking to some, however, it has deep roots in US history: from the Puritan colonists’ genocide against indigenous peoples in order to build their so-called ‘City upon a Hill’; to many of its founding fathers having been slave owners, who enshrined slavery in the Constitution; to the Federalist Papers which designed a complex system of separation of powers to guarantee freedom, but coldly discussed war and trade between countries; and to the country’s obsession with the right to bear arms, giving each person the right to kill in the name of freedom. Thus, we can see that Trump did not bring vulgarity to the United States, but only revealed the hidden tradition of the ‘commercial republic’ (it is worth noting that, in the Western tradition, merchants also tended to be plunderers and pirates).

Today, the United States has nearly completed this transformation of its identity: from a republic of values to a republic of commerce. This version of the country does not possess the united will to resume its position as leader of the world order, as evidenced by the strong and continued influence of the ‘America First’ rhetoric. The rising support among certain sections of the US population for such political vulgarity will encourage more politicians to follow this example.

The world order continues to be led by a number of powerful states, but is in the midst of great instability as efforts to strengthen the European Union have failed, Russia is likely to continue to decline, China is growing, Japan and South Korea lack real autonomy, and the United States, due to financial pressures, is rapidly shedding its responsibilities to support the network of post-war global multilateral institutions and alliances and instead seeks to build bilateral systems to maximise its specific interests. Put simply, the world order is falling apart; presently, the relevant questions are related to how rapid this breakdown will be, what an alternative new order should look like, and whether this new order can emerge and take effect in time to avoid widespread serious global instability.

China’s Role in Reshaping the World Order

A new international order has begun to emerge amid the disintegration of the old system. The main generative force in this dynamic is China, which is already the second-largest economy in the world and is a civilisation that is distinct from the West.

China is one of the largest countries in the world and its long history has endowed it with experiences that are relevant to matters of global governance. With its immense size and diversity, China contains a world order within itself and has historically played a leading role in establishing a tianxia system that stretched over land and sea, from Central Asia to the South Seas. Alongside its rich history, China has also transformed itself into a modern country over the past century, having learned from Western experiences and its own tradition of modernity. By sharing the wisdom of its ancient history and the lessons of its modern development, China can play a constructive role in global efforts to address imbalances in the world order and build a new system in three major ways.

1. The restoration of balanced global development. The classical order on the ‘world island’ (世界岛, shì jiè daǒ, roughly corresponding to Eurasia) leaned toward the continental nations, while the modern world order has been largely dominated by Western maritime powers. As a result, the world island became fractured, with the former centre of civilisation becoming a site of chaos and unending wars. Pax Americana was unable to establish a stable form of rule over the world island, as the United States was separated from this region by the sea and was unable to form constructive relations with non-Western countries. Therefore, the United States was only able to maintain a maritime order, rather than a world order. It relied on brutal military interventions into the centre of the world island, hastily retreating after wreaking havoc and leaving the region in a perpetual state of rupture.

Conversely, China’s approach to the construction of a new international order is that of ‘listening to both sides and choosing the middle course’ (执两用中, zhí liǎng yòng zhōng). Historically, China successfully balanced the land and sea; during the Han and Tang dynasties, for instance, China accumulated experience in interacting with land-based civilisations, meanwhile, since the Song and Ming dynasties, China has been deeply involved in the maritime trade system. It is based on this historical experience that China has proposed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), of which the most important aspect is the incorporation of the world island and the oceans, accommodating both the ancient and modern orders. The BRI offers a proposal to develop an integrated and balanced world system, with the ‘Belt’ aiming to restore order on the world island, while the ‘Road’ is oriented towards the order on the seas. Alongside this initiative, China has built corresponding institutions, such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).

2. Moving beyond capitalism and promoting people-centred development. The system on which Western power and prosperity has been built is capitalism, rooted in European legacies of the merchant-marauder duality and colonial conquest, driven by the pursuit of monetary profits, managing capital with a monstrously developed financial system, and hinging on trade. Under capitalism, the Western powers have viewed countries of the Global South as ‘others’, treating them as hunting grounds for cheap resources or markets. Although the Western powers have been able to occupy and spread capitalism to much of the world, they have not been able to widely cultivate prosperity, too often tending towards malicious opportunism; for those countries that do not profit from colonialism, but suffer from its brutal oppression, the system is nonviable. As a result, since the Western powers took charge of the world in the nineteenth century, the vast majority of non-Western countries have been unable to attain industrial or modern development, a track record which disproves the purported universality of capitalism.

The ancient Chinese sages advocated for a socioeconomic model that Dr Sun Yat-sen, a leader in the 1911 revolution to overthrow of the Qing dynasty and the first president of the Republic of China, called the ‘Principles of People’s Livelihood’ (民生主义, mínshēng zhǔyì) which can be rephrased as ‘the philosophy of benefiting the people’ (厚生主义, Hòushēng zhǔyì). This philosophy, which values the production, utilisation, and distribution of material to allow people to live better and in a sustainable manner, dates back over 2000 years, appearing as early as the Book of Documents (尚书, shàngshū), an ancient Confucian text. Guided by this philosophy, a policy of ‘promoting the fundamental and suppressing the incidental’ (崇本抑末, chóngběn yìmò) was adopted in ancient China to orient commercial and financial activities towards production and people’s livelihood. Today, China has rejuvenated this model and begun to share it with other countries through the BRI, which has taken the approach of teaching others ‘how to fish’, emphasising the improvement of infrastructure and advancement of industrialisation.

China, which is now the world’s factory and continues to upgrade its industries, is also driving a reconfiguration of the world’s division of labour: upstream, accepting components produced by cutting-edge manufacturing in Western countries; downstream, transferring productive and manufacturing capacity to underdeveloped countries, particularly in Africa. As the world’s largest consumer market, China should access energy from different parts of the world in a fair and even manner, and promote global policies which emphasise production (‘the fundamental’) and minimise financial speculation (‘the incidental’).

3. Towards a world of unity and diversity. When the European powers established the current world order, they generally pursued ‘homogenisation’, inclined to use violence to impose their system on other countries and inevitably creating enemies. The United States, influenced by Christian Puritanism, tends to believe in the uniformity of values, imposing its purported ‘universal values’ on the world, and denouncing any nation that differs from its conceptions as ‘evil’ and an enemy. During ‘the end of history’ period, this tendency was exemplified by the so-called War on Terror which launched invasions and missiles throughout the Middle East. Despite this preoccupation with homogenisation, the US-led order is being unravelled by rampant polarisation, broken apart by intensifying cultural and political divisions.

China, on the other hand, tells a different story. For millennia, based on the principle of ‘multiple gods united in one heaven’ or ‘one culture and multiple deisms’, various religious and ethnic groups have been integrated within China through the worship of heaven or the culture, thus developing the nation and the tianxia system of unity and diversity. Universal order or harmony can neither be attained through violent conquest nor through the preaching and imposition of values to change ‘the other’ into ‘self’, but rather by recognising the autonomy of ‘the other’; as emphasised in The Analects of Confucius (论语·季氏, lúnyǔ·jìshì), ‘…all the influences of civil culture and virtue are to be cultivated to attract them to be so; and when they have been so attracted, they must be made contented and tranquil’ (修文德以来之,既来之,则安之, xiūwén dé yǐlái zhī, jì lái zhī, zé ānzhī). By and large, it is along this path of harmony in diversity that China today conducts international relations.

China should understand the building of a new international order through the lens of revitalising the tianxia order, and its approach should be guided by the sages’ way of ‘harmonising all nations’ (协和万邦, xiéhé wànbāng) to pacify the tianxia. The process of constructing a new international order, or a revitalised tianxia order, should adhere to the following considerations:

1. A tianxia order will not be built at once but progressively. A Chinese idiom can be used to describe the China-led process of forming a new global system: ‘Although Zhou was an old country, the (favouring) appointment alighted on it recently’ (周虽旧邦,其命维新, zhōu suī jiù bāng, qí mìng wéixīn). Zhou was an old kingdom that was governed by moral edification; its influence gradually expanded, first to neighbouring states and then beyond, until two-thirds of the tianxia paid allegiance to the kingdom and the existing Yin dynasty (c. 1600–1045 BCE) was replaced by the Zhou dynasty (c. 1045– 256 BCE). In approaching the construction of a new international order and revitalising the concept of tianxia, China should follow this progressive approach to avoiding a collision with the existing hegemonic system. The concept of tianxia refers to a historical process without end.

2. Virtue and propriety are the first priority in maintaining the emerging tianxia system. A tianxia system aims to ‘harmonise all nations’, not to establish closed alliances or demand homogeneity. China should promote morality, decency, and shared economic prosperity in relations between nations and international law. What distinguishes this approach from the existing system of international law is that, in addition to clarifying the rights and obligations of each party, it also emphasises building mutual affection and rapport between nations.

3. A tianxia order will not seek to monopolise the entire world. The world is too large to be effectively governed by any country alone. The sages understood this and so their tianxia order never attempted to expand all over the known world at the time, nor did later generations; for instance, Zheng He came across many nations during his voyages to the Western Seas, but the Ming dynasty did not colonise and conquer them, nor did he include them all in the tributary system, but instead allowed them to make their own choices. Today, China does not seek to impose any system onto other countries; with such moderation, the struggle for hegemony can be avoided.

4. A new international order will consist of several regional systems. Instead of a world system governed by one dominant country or a small group of powers, a new global order will likely be made up of several regional systems. Across the world, countries with common geographies, cultures, belief systems, and interests have already begun to form their own regional organisations, such as in Africa, Asia, Latin America, the Middle East, and the Atlantic states; China should focus on the Western Pacific and Eurasia.

The concept of regional systems shares some similarities with Samuel Huntington’s division of civilisations, however, importantly, it does not necessitate any clash between them. As a large country and land-sea power, China will likely overlap with multiple regional systems, including both maritime- and land-based regional systems. China, which literally means ‘the country of the middle’, should serve as a harmoniser between different regional systems and act to mitigate conflict and confrontation; in this way, a new international order of both unity and diversity can emerge.

A new architecture of global governance will be built gradually, with layers nested upon each other from the inside out. To this end, China’s efforts should begin in the innermost layer to which it belongs, East Asia. Traditionally, China, the Korean peninsula, Vietnam, Japan, and other countries in this region formed a Confucian cultural sphere; however, after the Second World War, despite these nations successfully modernising, relations between them have deteriorated due to the pressures of foreign powers, such as the United States and Soviet Union. China’s efforts to reorganise the world order must start from here, by revitalising this shared heritage, developing coordinated regional policies based on the ‘Principles of People’s Livelihood’, and demonstrating improved standards of prosperity and civility for the world. As the achievements and strength of such regional efforts grow, the power of the United States and its world order will inevitably fade out, and the process of global transformation will rapidly accelerate.

After the inner layer of East Asia, the next-most nested layer, or middle layer, that China should focus on is the heart of the world island, Eurasia. Central to these regional efforts is the SCO, in which China, Russia, India, and Pakistan are already member states, Iran and Afghanistan are observer states, and Turkey and Germany can be invited. Due to its economic decline and weakening global influence, Russia is likely to increase its focus on its neighbouring regions, namely Central Asia, and to participate more actively in the SCO, including assisting in efforts to promote harmonious relations and development in the region and minimising conflict. The stability of Eurasia is key, not only to the security and prosperity of China, particularly its western regions, but to overall global peace.

Finally, the outermost layer for China is the institutionalised BRI, which connects nations and regions across the world. Proposed by President Xi Jinping in 2013, to date China has signed more than 200 BRI cooperation agreements with 149 countries and 32 international organisations.

Concluding Remarks

The evolution and future direction of the world order cannot be understood without examining the shifting relationship between China and the West over the past five centuries. In the early modern era, the Western powers were inspired by China in their pursuit of modernisation; in the past century, China has learned from the West. The re-emergence of China has shaken the foundations of the old Western-dominated world order and is a driving force in the formation of a new international system. Amid the momentous changes in the global landscape, it is necessary to recognise the strengths and limits of Western modernity, ideologies, and institutions, while also appreciating the Chinese tradition of modernity and its developments in the current era. For China, this requires a restructuring of its knowledge system, guided by a new vision which is inspired by classical Chinese wisdom: ‘Chinese learning as substance, Western learning for application’ (中学为体,西学为用, Zhōngxué wèi tǐ, xīxué wèi yòng).

Bibliography

Hamilton, Alexander, John Jay, and James Madison. The Federalist Papers [联邦党人文集]. Translated by Cheng Fengru, Han Zai, and Xun Shu. The Commercial Press, 1995.

Yao, Zhongqiu. The Way of Yao and Shun: The Birth of Chinese Civilisation [尧舜之道:中国文明的诞生]. Hainan Publishing House, 2016.

Zhu, Qianzhi. The Influence of Chinese Philosophy on Europe [中国哲学对欧洲的影响]. Hebei People’s Publishing House, 1999.

Author’s Notes

1. During the early fifteenth century, the Ming dynasty (1388–1644) sponsored a series of seven ocean voyages led by the Chinese navigator and diplomat Zheng He (1371–1433). Over a thirty-year period, these naval missions travelled from China to Southeast Asia, India, the Horn of Africa, and the Middle East. ↑

2. Tianxia is an ancient Chinese worldview which dates back over four thousand years and roughly translates to ‘all under heaven’, or the Earth and living beings under the sky. Incorporating moral, cultural, political, and geographical elements, tianxia has been a central concept in Chinese philosophy, civilisation, and governance. According to this belief system, achieving harmony and universal peace for tianxia, where all peoples and states share the Earth in common (天下为公 tiānxià wèi gōng), is the highest ideal. ↑

3. See Yao Zhongqiu, The Way of Yao and Shun: The Birth of Chinese Civilisation [尧舜之道:中国文明的诞生] (Hainan Publishing House, 2016), 64–74. ↑

4. Scholar-officials were intellectuals appointed to political and government posts by the emperor of China. This highly educated group formed a distinct social class which dominated government administration within imperial China. ↑

5. For further reading on this topic, see Zhu Qianzhi, The Influence of Chinese Philosophy on Europe [中国哲学对欧洲的影响] (Hebei People’s Publishing House, 1999). ↑

6. Alexander Hamilton, John Jay, and James Madison, The Federalist Papers [联邦党人文集], trans. Cheng Fengru, Han Zai, and Xun Shu (The Commercial Press, 1995). ↑

This article was published earlier in Dongsheng and is republished under the Creative Commons license CC 4.0

Feature Image: Detail from Catalan Atlas (circa 1375) depicting Marco Polo’s caravan on the Silk Road. Abraham Cresques / Wikimedia Commons.