India was the world’s leading cotton and textile producer for millenniums. In the 1990s the traditional ‘desi’ variety of cotton was upstaged by imported hybrid cotton varities in the hopes of increased production and profits. They soon became vulnerable to pests and resulted in increased use of fertilisers and pesticides, thus increasing the production costs. The failure of hubrid cotton led to the introduction of Bt cotton in 2002 as India’s first genetically modified crop. GM crops have been strongly opposed by increasing believers of traditional agriculture and scientists, possibly for very good reasons. India’s cotton production has quadrupled by 2010 and proponents of GM crops have attributed this to Bt cotton. This has been hotly contested. The recent assertion in favour of Bt cotton by Dr Ramesh Chander of Niti Aayog, early this year, has come under scathing criticism in an article by Professor Andrew Paul Gutierrez, Dr. Hans R.Herren, and Dr. Peter E.Kenmore as also by Sujatha Byravan. The claims by the advocates of GM crops and Bt cotton were questioned in a well-researched article early this year by scientists K R Kranthi and G D Stone. This article counters their arguements.

– TPF

This article was originally posted on the non-profit GeneticLiteracyProject.org website.

Authors: Cameron English, Jon Entine, and Matin Qaim

Was the introduction of transgenic (GMO) cotton seeds to India in 2002 the beginning of the renaissance of the country’s then struggling cotton industry? Or was it a non-event, hyped by biotechnology advocates, especially agro-businesses, to bolster the case for a technology struggling for public acceptance?

After years of farmers losing crops to tobacco budworms, cotton bollworms and pink bollworms, costing billions of dollars a year in losses, Monsanto developed insect-resistant Bt cotton in the early 1990s. The engineered crop has become widespread since its commercial release in China and the United States in 1996, followed by its introduction to India in 2002.

Within just a few years, India’s troubled cotton industry had done a 180, emerging as one of the world’s largest producers of GMO cotton, as exports boomed, helping to fuel India’s rapid rise as an emerging nation. But not everyone accepts this version of events. Agricultural biotechnology critics maintain that the success of Bt cotton was more smoke and mirrors than science, a story deceptively promoted by the beleaguered agricultural biotechnology industry and its supporters

Competing research conclusions

The Bt cotton debate was reignited this year following the publication of contrasting scholarly analyses, one challenging the success narrative and several others defending it. The latest volley of criticism was launched in March when Indian entomologist K. R. Kranthi and Washington University anthropologist Glenn Davis Stone wrote a scathing analysis of Bt cotton success claims in Nature Plants, an article widely disseminated by the global media. Reviewing 20 years of data, the authors claimed that the dramatic success of India’s first (and only) GMO crop was largely hype, and may have even been a failure. According to Stone in a press release put out by Washington University in St. Louis:

Yields in all crops [in India] jumped in 2003, but the increase was especially large in cotton,” Stone said. “But Bt cotton had virtually no effect on the rise in cotton yields because it accounted for less than 5% of India’s cotton crop at the time.

Now farmers in India are spending more on seeds, more on fertilizer and more on insecticides …. Our conclusion is that Bt cotton’s primary impact on agriculture will be its role in making farming more capital-intensive — rather than any enduring agronomic benefits.

That led to a rebuke by long-time scholars in the field. In early May, four scientists at the South East Asia Biotechnology Center in New Dehli weighed in with their own take down in the open access Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Publication bioRxiv, concluding:

This study [Kranthi and Stone] conspicuously ignores positive shifts that occurred with Bt adoption at reduced real cost of production in all states resulting in large welfare benefits netting out increased cost of cultivation. [The fallacy] associated with increasing yield trends even before [the] introduction of Bt cotton as claimed by Kranthi and Stone does not stand [up to] scrutiny of increasing yield trends from 2002-03 to 2009-10, with some years showing significant yield dips due to drought [only] to bounce back …. in 2017-18. The ignorance of drought impact tends to attribute the yield reduction entirely [to] the failure of Bt technology.

In June, GLP published a detailed critique by plant geneticist Deepak Pental, who wrote:

The article’s authors claim to have carried out ‘a new analysis of unprecedented scope, time depth and detail’ on cotton cultivation in India to find the real reasons behind the doubling of yields between 2000 and 2006, followed by yield stagnation. While the avowed goal of the analysis is to set the record right on the contribution of the Bt trait to cotton cultivation in India, the real purpose of the report is to cast doubts on the utility of GE technologies.

Most recently, a number of scientists who have crunched the data responded sharply to the Stone-Kranthi hypothesis in letters published in Nature Plants. One of the most prominent is Ian Plewis, an emeritus professor at the University of Manchester in England, who has written extensively on debunked claims that the introduction of Bt cotton led to a surge in farmer suicides in India. Last year, he analyzed much of the same data cited by Stone and Kranthi in a paper in the Review of Agrarian Studies, arriving at a much more nuanced conclusion.

The conclusions from these analyses are mixed. The more expensive Bt hybrid seeds have lowered insecticide costs in all three States, but only in Rajasthan did yields increase. An important message of this paper is that conclusions about the effectiveness of Bt cotton are more nuanced than many researchers and commentators recognise. The paper does not refute the assertions about the success of Bt cotton, but it does show that the benefits are not evenly distributed across India.

In a letter to the journal, Plewis challenged Kranthi’s and Stone’s methodology.

Kranthi and Stone do not present state-wide analyses of insecticide use, relying instead on unpublished market research data for India as a whole. Their assertion that farmers are spending more on insecticide than they were before the introduction of Bt is not supported by my analyses which are based on publicly available data and show that the technology reduced the proportion of farmers’ costs going to insecticides in all three states.

Kranthi and Stone make some important points but their approach prevents them from reaching soundly based assessments of the long-term impacts of Bt cotton on Indian farmers in different states.

Other critics were equally challenging of their data. In a letter originally published in Nature Plants, agricultural economist Matin Qaim, who has been writing about the impacts of Bt cotton in India since its introduction, jumped into the fray:

Kranthi and Stone’s attempt to analyze long-term effects of Bt cotton is laudable, as the effects of the technology can change over time due to evolving pest populations and other dynamics. However, their claim that Bt contributed little to the yield increases observed in India between 2002 and 2008 is unconvincing ….

Strong arguments on both sides. What do the facts say? Let’s separate the cotton from the sharp ends of the boll.

What is Bt cotton?

Bt seeds produce over 200 different Bt toxins, each harmful to different insects. Bt cotton is an insect-resistant transgenic crop (GMO) designed to combat many destructive insects, most notably the bollworm. It was created by genetically altering the cotton genome to express a natural, non-pathogenic microbial protein from the bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis that is found in the soil. Bt in its natural and transgenic forms has been extensively evaluated and found to be safe to all higher animals tested. Bt has been used as an insecticide in organic farming since the middle of the 20th century.

Traditionally, pesticides have been used to combat the cotton bollworm. However, in developing nations like India, the expense of using large amounts of pesticide is often too high for marginal farmers. Bt cotton was developed with the intention of reducing the amount of pesticide needed for cotton cultivation, thereby reducing production costs for farmers, environmental impact, and the pesticide exposure of applicators, often women and children.

Numerous independent studies have attributed anywhere from 14-30% of the cotton yield increase in India to the cultivation of Bt seeds. Five years after the introduction of Bt cotton, a professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University and visiting fellow at Centre de Sciences Humaines, New Delhi would write in the Wall Street Journal about India’s recently flagging cotton production: “By 2007-08, India became the largest producer of cotton with the largest acreage under Bt cotton in the world, pushing China into second place.” Many scientists and news organizations cited the surge in production of Indian cotton as one of the clearest GMO success stories.

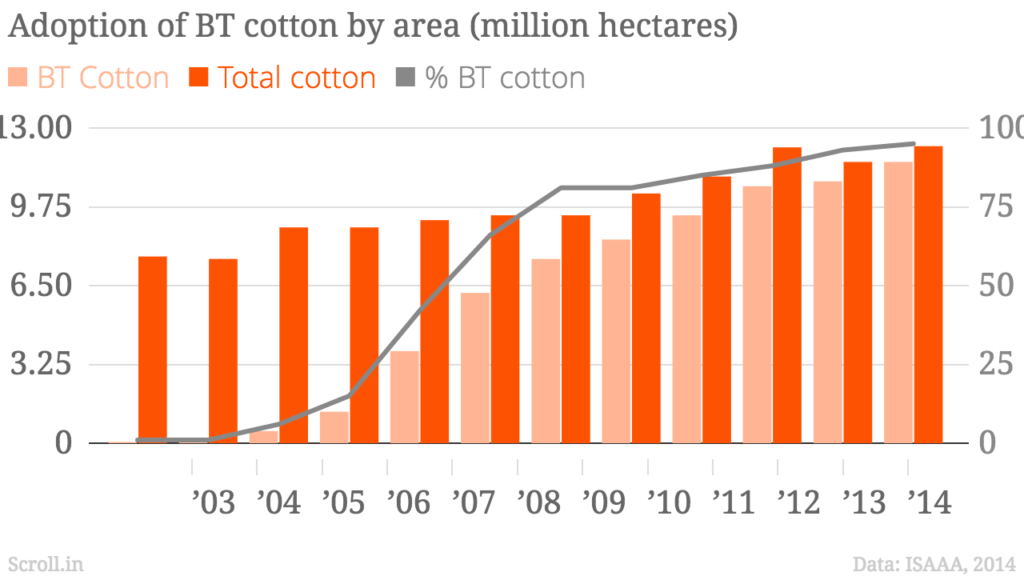

After its introduction, within a decade, Bt cotton accounted for more than 95% of all cotton cultivation in India, as yields increased.

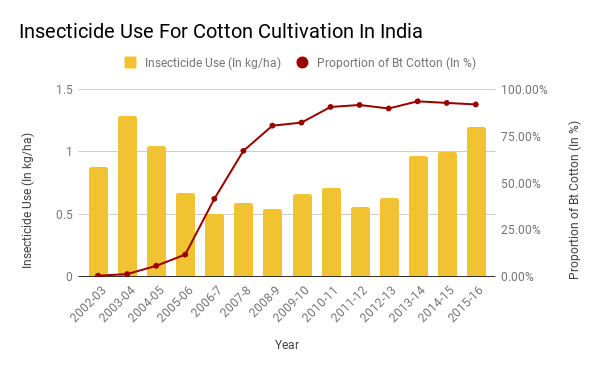

During that same period marking a 55% rise in yields, overall use of insecticides remained below absolute levels from 2003, while per- hectare usage dropped precipitously.

Stone’s critique and pink bollworm resistance

Despite its initial success, Bt cotton seed is more costly than non-transgenic (but lower yielding) varieties, making it a target for some critics who are skeptical of crop biotechnology. One of those longtime skeptics is Washington University professor Stone. Stone is part of a cohort of scholars and activists, including Indian-philosopher Vandana Shiva, which fervently believes that the Indian Green Revolution that dramatically reduced hunger and is credited with saving more than a billion lives was a failure.

As far back as 2012, Stone challenged a plethora of studies generally supporting the view behind the success of India’s Bt cotton crops and the resurrection of the nation’s once-threatened cotton industry. Stone looked at the data from a cultural anthropology perspective and saw more hype than substance. Writing in his influential paper in 2012, “Constructing Facts: Bt Cotton Narratives in India,” Stone maintained, “We simply cannot say how Bt seed has affected cotton production in India.” The “triumph narrative” of Bt cotton in India, he claimed, “flows mainly from economists and the biotech industry (and its academic allies)” in “industry-journal authentication systems” (peer-reviewed journals), which “serve the interests of their constituent parties.” The arrangement is a “cosy alliance between GM manufacturers and ostensibly independent researchers,” he added.

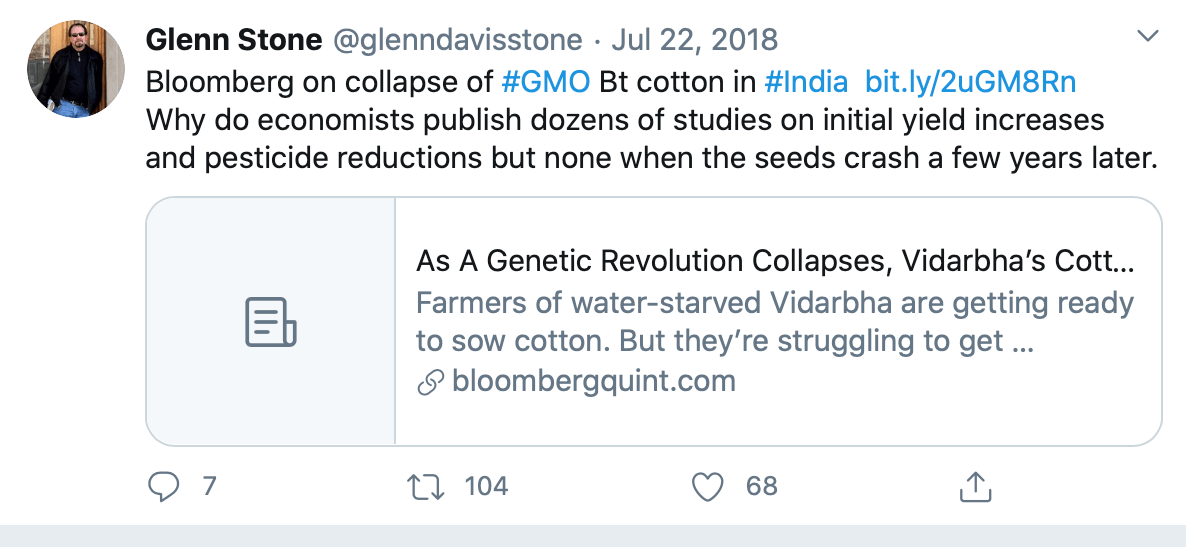

Problems emerged in 2017, as the pink bollworm ravaged cotton crops in India, suggesting the pest had developed resistance. A January 2018 study released by Central Institute of Cotton Research (CICR) showed how the proportion of pink bollworm on green bolls of Bt cotton plants in Maharashtra, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh rose from 5.71 percent in 2010 to 73.82 percent in 2017. GMO-skeptic Stone tweeted a link to a scathing article in Bloomberg, sarcastically asking why GMO supporters seemed to be ignoring the Bt’s failure in India.

As reporter Mark Lynas noted in an analysis for the Cornell Alliance for Science, the debate is nuanced than either pro or anti factions often maintain. The Bloomberg report did notice that similar problems have not turned up in Australia and China, where Bt cotton is grown, suggesting the resistance may be unique to conditions in India. Lynas interviewed Ronald Herring, author of numerous peer-reviewed papers on the impacts of Bt cotton in India. He acknowledged the reality of the problem, but suggested the issue was murky. The problem could be linked to a variety of issues, including the use of counterfeit Bt seeds, which are rampant in India, or the fact that many financially-pressed Indian farmers abandoned the recommended rotations of a second crop, which can be less profitable than the cash-crop cotton.

Bt cotton has had an up and down history in India. From 2002 to 2009, cotton production, productivity and acreage grew steadily. Soon, the pink bollworm began developing resistance. Studies between 2013 and 2015 of Indian Council of Agricultural Research and CICR concluded that pink bollworm had developed resistance to Bollgard-II. Insecticide use shot up to levels not seen in a decade.

Vijay Paranjape, the associate director of the USAID-funded Bt brinjal project in Bangladesh, and an expert in Bt cotton in India, told Lynas that the problem was largely focused in one region, Vidarbha. “[T]here is some pattern to it that could be due to [poor] agronomic practices being followed,” in that area. In other words, the facts are complicated.

Another Bt expert, Srinivasan Ramasamy, then a visiting scientist at Cornell University, told Lynas: “I don’t agree that Bt cotton has failed in India.” Ramasamy, he said, pointed out that Bt cotton “was developed against three different bollworms — Helicoverpa armigera, Earias spp. and Pectinophora gossypiella” (the latter is pink bollworm).

Bt cotton effectively reduced these bollworms, except the pink bollworm, that too in Maharashtra only. If the other two species remained as a major threat, the pesticide use might have been several-folds higher than the current use. Hence, Bt cotton has contributed to pesticide reduction.

Stone’s disputations and Qaim’s response

This nuanced history of course is often not reflected in the commentaries, or even academic studies, by supporters of GMO crops. Setbacks are often portrayed by hardened critics as absolute failures.

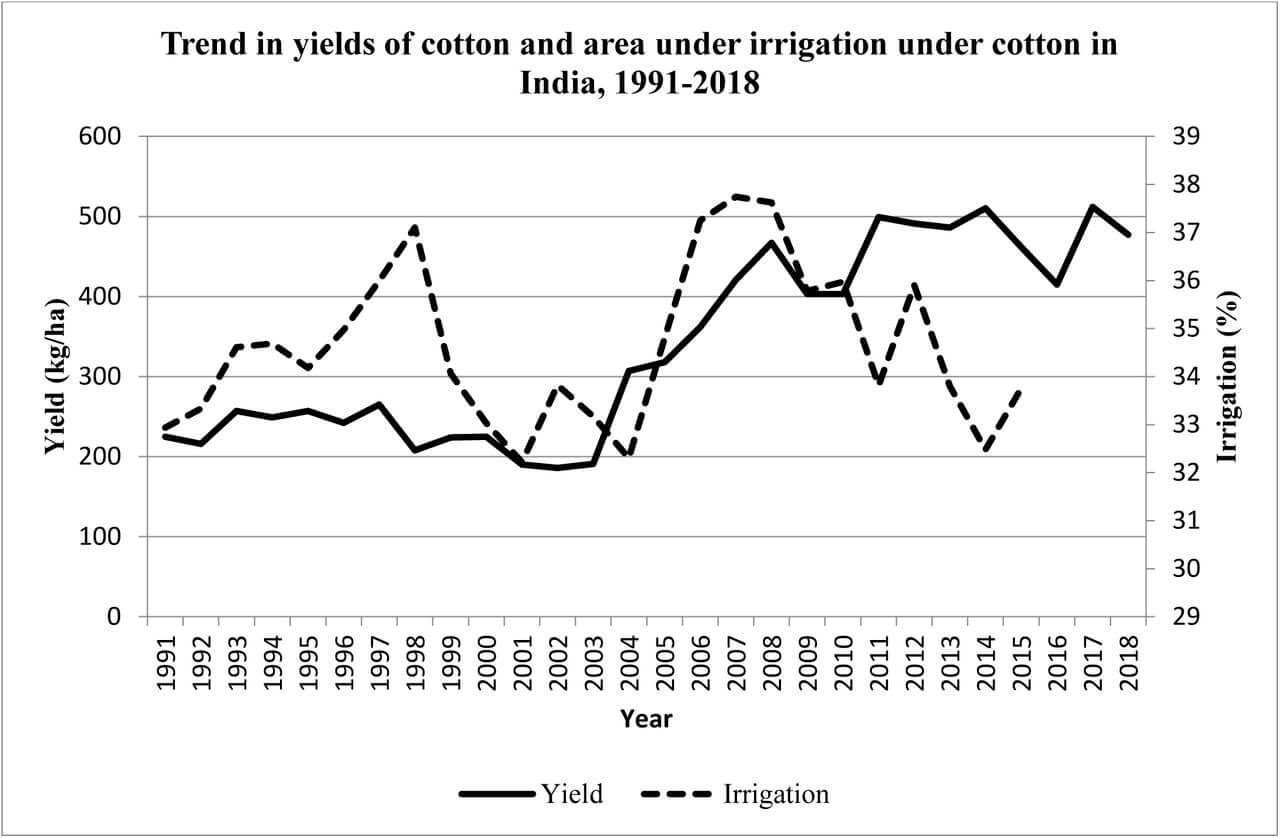

Jump to 2020, and Stone, joined by K. R. Kranthi, the former director of India’s Central Institute for Cotton Research and now the head of a technical division at the Washington-based International Cotton Advisory Committee, reemerged as a sharp critic of Bt cotton—though the success narrative appears even stronger now. Since 2012, water usage has dropped sharply in Indian while Bt cotton yields have continued to climb, and are at or near historic highs, up more than 150% since the early 2000s.

Despite these numbers, Kranthi and Stone argued that “the largest production gains came prior to widespread [Bt] seed adoption and must be viewed in line with changes in fertilization practices and other pest population dynamics.” They also cited the pink bollworm’s evolved resistance to Bt insecticide and the threat posed by other pests that are impervious to the insecticidal power of Bt cotton.

Qaim found these arguments lacking, however. Building on previous scholarship, the agricultural economist explains that, when other relevant factors are accounted for, Bt cotton did indeed boost crop yields in India. Here are his conclusions:

The agronomic and socioeconomic effects of insect-resistant Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) cotton in India have long been debated. In their recent Perspective article, Kranthi and Stone [1] used 20 years of data to analyze associations between the adoption of Bt cotton, crop yields and insecticide use, claiming that Bt technology had little yield effects and did not produce any enduring benefits.

Here, I argue that the methods used by Kranthi and Stone are not suitable to make statements about causal effects, so their conclusions are misleading. As earlier studies showed [2–7], Bt cotton has contributed to sizeable yield gains and important benefits for cotton farmers and the environment. Kranthi and Stone’s attempt to analyze long-term effects of Bt cotton is laudable, as the effects of the technology can change over time due to evolving pest populations and other dynamics.

However, their claim that Bt contributed little to the yield increases observed in India between 2002 and 2008 is unconvincing, as this part of their analysis looks at the same time period that was also analyzed previously by other authors with more precise microlevel data and better methodologies [7,8]. Kranthi and Stone use simple graphical analysis to compare time trends for Bt adoption, fertilizer use and yield at national and state levels.

Comparing the graphs, they find a stronger correspondence between the fertilizer and yield trends than between the Bt adoption and yield trends. Thus, they conclude that the observed yield increases were primarily due to the higher use of fertilizer and other inputs, and not to Bt technology. The problem is that such a simple graphical comparison of time trends is inappropriate to analyze causal effects. Crop yields may increase because of more fertilizer or because of better pest control through the adoption of insect-resistant Bt varieties. It is also possible that some farmers decided to use more fertilizer because of Bt adoption. Many other factors, such as changes in irrigation, other inputs and technologies, agronomic practices, training of farmers or simple weather fluctuations may also affect cotton yields and broader socioeconomic benefits.

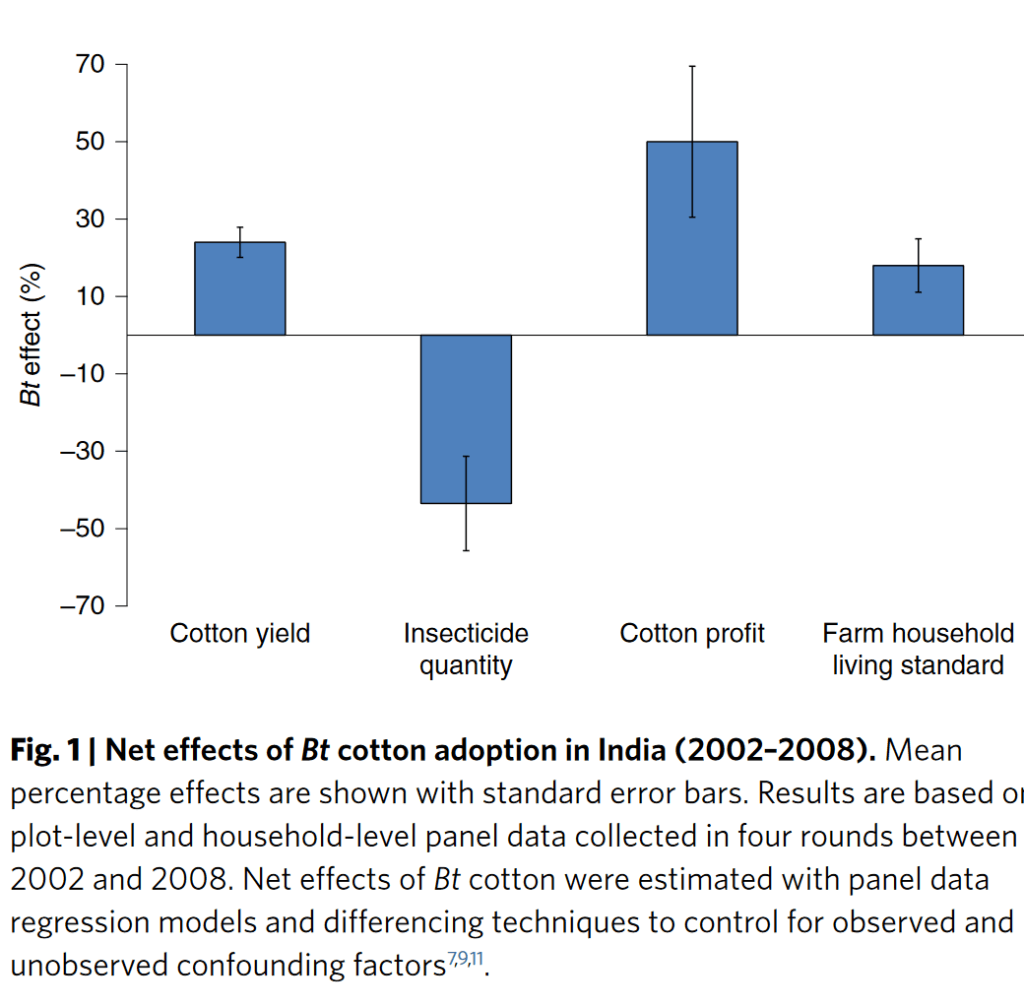

In principle, Kranthi and Stone acknowledge these complexities but they do nothing to control for any of the confounding factors. Previous studies used microlevel data and more sophisticated statistical techniques to control for confounding factors and possible bias, hence leading to more reliable effect estimates. Kathage and Qaim [7] used panel data collected between 2002 and 2008 from over 500 randomly selected cotton farms in four states of India. They used statistical differencing techniques and controlled for the use of fertilizer, irrigation, pesticides, agronomic practices and many other factors, including location and time trends, to deal with selection bias and cultivation bias.

Results showed that—after controlling for all other factors—Bt adoption had increased cotton yields by 24%, farmers’ profits by 50% and farm household living standards by 18%, with no indication that the benefits were fading during the 2002–2008 period. The same data also revealed that chemical insecticide quantities declined by more than 40% through Bt adop-tion, with the largest reductions in the most toxic active ingredients previously sprayed to control the American bollworm [9–11].

There are not many other examples from India or elsewhere where a single technology has caused agronomic, economic and environmental benefits in a similar magnitude.Against this background, Kranthi and Stone’s statement that “the surge in yields has been uncritically attributed to Bt seed” is not correct. Of course, there are other factors that contributed to the observed doubling of yields between 2002 and 2008 but the 24% estimate by Kathage and Qaim is the net effect of Bt technology after controlling for other factors [7]. Using longer-term data but inap-propriate methodologies to challenge earlier results, as Kranthi and Stone do in their article, is not convincing. Bt cotton has increased yields through better pest control and has benefited adopting farm-ers in India and several other developing countries [12–14].

References

1. Kranthi, K. R. & Stone, G. D. Long-term impacts of Bt cotton in India. Nat. Plants6, 188–196 (2020).

2. Datta, S. et al. India needs genetic modification technology in agriculture. Curr. Sci.117, 390–394 (2019).

3. Qaim, M. The economics of genetically modified crops. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ.1, 665–693 (2009). Bt cotton, yields and farmers’ benefitsMatin Qaim ✉arising from K. R. Kranthi and G. D. Stone Nature Plants https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-020-0615-5 (2020)–70–50–30–1010305070Cotton yieldInsecticidequantityCotton profitFarm householdliving standardBt effect (%)Fig. 1 |Net effects of Bt cotton adoption in India (2002–2008). Mean percentage effects are shown with standard error bars. Results are based on plot-level and household-level panel data collected in four rounds between 2002 and 2008. Net effects of Bt cotton were estimated with panel data regression models and differencing techniques to control for observed and unobserved confounding factors 7,9,11 Nature Plants| www.nature.com/natureplants matters arisingNature PlaNts

4. Crost, B., Shankar, B., Bennett, R. & Morse, S. Bias from farmer self-selection in genetically modified crop productivity estimates: evidence from Indian data. J. Agric. Econ.58, 24–36 (2007).

5. Qaim, M., Subramanian, A., Naik, G. & Zilberman, D. Adoption of Bt cotton and impact variability: insights from India. Rev. Agric. Econ.28, 48–58 (2006).

6. Subramanian, A. & Qaim, M. The impact of Bt cotton on poor households in rural India. J. Dev. Stud.46, 295–311 (2010).

7. Kathage, J. & Qaim, M. Economic impacts and impact dynamics of Bt(Bacillus thuringiensis) cotton in India. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA109, 11652–11656 (2012).

8. Krishna, V., Qaim, M. & Zilberman, D. Transgenic crops, production risk and agrobiodiversity. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ.43, 137–164 (2016).

9. Krishna, V. V. & Qaim, M. Bt cotton and sustainability of pesticide reductions in India. Agric. Syst.107, 47–55 (2012).

10. Veettil, P. C., Krishna, V. V. & Qaim, M. Ecosystem impacts of pesticide reductions through Bt cotton adoption. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ.61, 115–134 (2017).

11. Kouser, S. & Qaim, M. Impact of Bt cotton on pesticide poisoning in smallholder agriculture: a panel data analysis. Ecol. Econ.70, 2105–2113 (2011).

12. Ali, A. & Abdulai, A. The adoption of genetically modified cotton and poverty reduction in Pakistan. J. Agric. Econ.61, 175–192 (2010).

13. Qiao, F. Fifteen years of Bt cotton in China: the economic impact and its dynamics. Wo r l d D e v.70, 177–185 (2015).

14. Qaim, M. Role of new plant breeding technologies for food security and sustainable agricultural development. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy42, 129–150 (2020)

Matin Qaim is a professor in the Department of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development at the University of Goettingen in Germany. Visit his website. Follow Matin on Twitter @MatinQaim

The letter was originally published in Nature Plants and has been republished here with permission. Nature Plants can be found on Twitter @NaturePlants

Cameron English is a Science writer and the Managing Editor at Genetic Literacy Project.

Jon Entine is a renowned journalist, author, though-leader and the Founder and Executive Director of the Genetic Literacy Project.

This article is republished from the Genetic Literacy project under the Creative Commons 4.0

Image Credit: GLP and India Times