“The history of money is entering a new chapter”. The RBI needs to heed this caution and not be defensive.

Cryptocurrency will be discouraged by the government was the message from the FM during the budget discussion in parliament. There will be heavy taxation and no relief in capital gains for past losses. But, India has to contend with growing use of cryptos in these uncertain times. Russian kleptocrats are reportedly using cryptos to evade sanctions. Ukraine which has been a center for cryptos trading due to its lax rules is now using them to get funds.

President Joe Biden recently signed an executive order requiring government agencies to assess use of digital currency and cryptos due to their growing importance. The Indian authorities have also been trying to bring legislation to deal with the issue since October 2021. Would the US clarifying its position help India also decide on cryptos?

The SC has asked the government to clarify its position on the legality of cryptos. The FM in the Budget 2022-23 proposed taxing the capital gains and crypto transactions but did not declare them illegal. The RBI Governor was more expansive in February when he highlighted three things. First, “Private cryptocurrencies are a big threat to our financial and macroeconomic stability”. Second, investors are “investing at their own risk” and finally, “these cryptocurrencies have no underlying (asset)… not even a tulip”. Subsequently, a RBI Deputy Governor called cryptos worse than a Ponzi scheme and suggested that they not be “legitimized”. It is only recently that the RBI has announced that it will float Central Bank Digital Currency (CBDC)

Difficult to Declare Cryptos Illegal

The governor calling cryptos as cryptocurrency has unintentionally identified them as a currency. His statements indicate RBI’s worry about its place in the economy’s financial system as cryptos proliferate and become more widely used. This threat emerges from the decentralized character of cryptos based on the Blockchain technology which the Central Banks cannot regulate and which enables enterprising private entities (like, Satoshi Nakamoto initiated Bitcoins in 2009) to float cryptos which can function as assets and money.

The total valuation of cryptos recently was upward of $2 trillion – more than the value of gold held globally. Undoubtedly, this impacts the financial systems and sovereignty of nations. So, the RBI rather than be defensive needs to think through how to deal with cryptos.

Cryptos which operate via the net can be banned only if all nations come together. Even then, tax havens may allow cryptos to function defying the global agreement. They have been facilitating flight of capital and illegality in spite of pressures from powerful nations.

The genie is out of the bottle. The total valuation of cryptos recently was upward of $2 trillion – more than the value of gold held globally. Undoubtedly, this impacts the financial systems and sovereignty of nations. So, the RBI rather than be defensive needs to think through how to deal with cryptos.

Cryptos as Currency

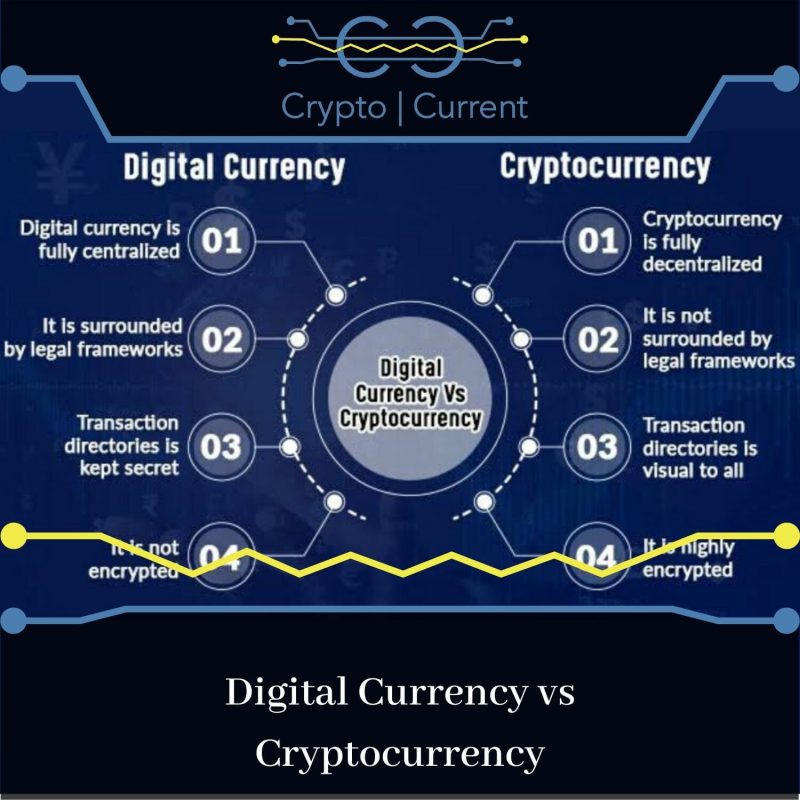

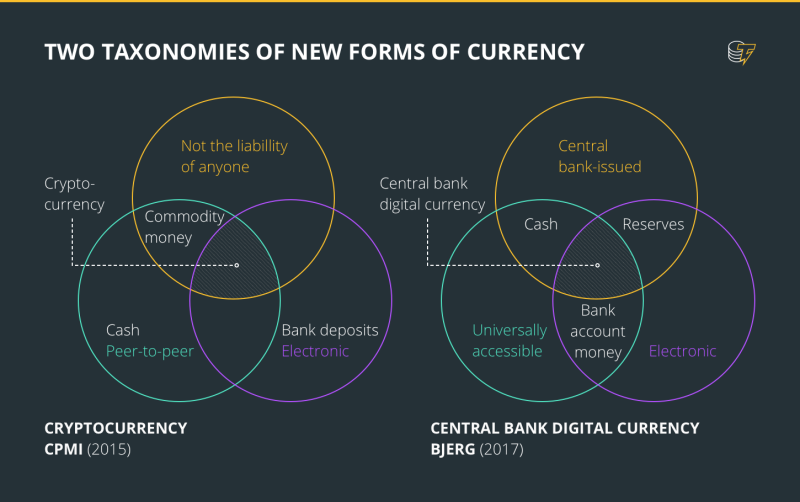

Source: Crypto-current.co

Will a CBDC help tackle the emerging problem? Indeed not, since it can only be a fiat currency and not a crypto. However, cryptos can function as money. This difference needs to be understood.

A currency is a token used in market transactions. Historically, not only paper money but cows and copper coins have been used as tokens since they are useful in themselves. But paper currency is useless till the government declares it to be a fiat currency. Everyone by consensus then accepts it at the value printed on it.

So, paper currency with little use value derives its value from state backing and not any underlying commodity. Cryptos are a string of numbers in a computer programme and are even more worthless. And, without state backing. So, how do they become acceptable as tokens for exchange?

Their acceptability to the rich enables them to act as money. Paintings with little use value have high valuations because the collectivity of the rich agrees to it. Cryptos are like that.

Bitcoin, the most prominent crypto, has been designed to become expensive. Its total number is limited to 21 million and progressively it requires more and more of computer power and energy to produce (called mining like, for gold). As the cost of producing the Bitcoin has risen, its price has increased. This has led to speculative investment which drives the price higher, attracting more people to join. So, since 2009, in spite of wildly fluctuating prices, they have yielded high returns making speculation successful.

Unlike the Tulip Mania

The statement that cryptos have no underlying asset, not even a tulip refers to the time when tulip prices rose dramatically before they collapsed. But, tulips could not be used as tokens, while cryptos can be used via the internet. Also, the supply of tulips could expand rapidly as its price went up but the number of Bitcoins is limited.

So, cryptos acquire value and become an asset which can be transacted via the net. This enables them to function as money. True, transactions using Bitcoins are difficult due to their underlying protocol, but other simpler cryptos are available.

The different degrees of difficulties underlying cryptos arises from the problem of `double spending’. Fiat currency whether in physical or electronic form has the property that once it is spent, it cannot be spent again, except fraudulently, because it is no more with the spender. But, a software on a computer can be repeatedly used.

Blockchain and encryption solved the problem by devising protocols like, the `proof of work’ and `proof of stake’. They enable the use of cryptos for transactions. The former protocol is difficult. The latter is simpler but prone to hacking and fraud. Today, thousands of different kinds of cryptos exist – Bitcoin like cryptos, Alt coins and Stable coins. Some of them may be fraudulent and people have lost money.

CBDC, Unlike Cryptos

Source: cointelegraph.com

Blockchain enables decentralization. That is, everyone on the crypto platform has a say. But, the Central Banks would not want that. Further, they would want a fiat currency to be exclusively issued and controlled by them. But the protocols mentioned above theoretically enable everyone to `mine’ and create currency. So, for CBDC to be in central control, solve the `double spending’ problem and be a crypto (not just a digital version of currency) seems impossible.

A centralized CBDC will require RBI to validate each transaction – something it does not do presently. Once a currency note is issued, RBI does not keep track of its use in transactions. Keeping track will be horrendously complex which could make the crypto like CBDC unusable unless new secure protocols are designed. No wonder, according to IMF MD, “… around 100 countries are exploring CBDCs at one level or another. Some researching, some testing, and a few already distributing CBDC to the public. … the IMF is deeply involved in it ..”

Conclusion

Issuing CBDCs will not only be complicated but presently cannot be a substitute for cryptos which will eventually be used as money. This will impact the functioning of the Central Banks and commercial banks. Further, it is now too late to ban cryptos unless there is global coordination which seems unlikely. The rich who benefit from cryptos will oppose banning them. Can the US work out a solution? The IMF MD has said, “The history of money is entering a new chapter”. The RBI needs to heed this caution and not be defensive.

Slightly shortened version of this article was published earlier in The Hindu.

Feature Image Credit: doralfamilyjournal.com