Led by the Department of Industrial Policy & Promotion, Ministry of Commerce, the Make in India policy (“MII”) extends to 25 focused sectors. Among these is the defence sector, where the nature of the sector renders MII extremely important and relevant. This is outlined by India’s status as the second-largest standing army and third-largest military spender in the world.[1] Yet, it remains the second-largest arms importer and its exports merely amount to 0.2% of the global pie.[2] China is the fifth-largest arms exporter at 5.5% of the global share.[3] However, this is likely to fall in the post-pandemic world, where China’s credibility has been severely tainted.[4] This represents an opportunity for Indian defence manufacturers to attract present and future foreign investment.

Against this background, MII was enacted with two objectives: (1) to increase domestic manufacturing of defence equipment; and (2) address the national security interest of self-sufficiency over key technologi. There are two ways in which technology up-gradation can happen: (1) indigenous efforts; and (2) transfer of technology, through international agreements. In this article, I flag the main challenges to argue that India has significantly underperformed in both. Subsequently, I propose macro-policy changes to address identified challenges.

Evaluating technological upgradation in the Defence sector in india

- Evaluating ‘Indigenous Efforts’

Indigenous efforts are confronted with three main challenges:

- Inadequate Investment for Research & Development (R&D)

Only 5.7% of the defence budget is allocated to R&D,[5] despite successive parliamentary committees recommending at least 10% to meet minimum requirements.[6] The average allocation among global rivals like USA, UK, France, and China is well above 15%.[7] Even private-sector players in India, like Tata, L&T, and Mahindra and Mahindra, invest less than 1% of their turnover in R&D, as against the average of 10% in the aforementioned countries.[8] The producer lacks the basic R&D required even for making marginal improvements in performance to the product, or altering it based on user-specifications.[9] The effect of this is that the resulting product is obsolete in an already disruptive market. Thus, a buyer, even if domestic, is unwilling to accept such an obsolete product at higher prices merely for the sake of indigenous production.

- Shortage of Skilled Workforce

A skilled workforce is the key to achieving self-sufficiency in defence manufacturing because of the highly specialized nature of this sector and the workforces’ vision and skills determine the efficacy of the produced/procured domestic technology. This shortage exists at both the research and procurement level.

At the research level, there is a severe shortage of skilled human resources, in terms of quantity and quality, at R&D organizations like DRDO.[10] With more than 3,500 engineering colleges producing about 1.5 million engineering graduates annually, India has an unparalleled talent availability.[11] However, only 17.5% of these graduates are employable because colleges lack proper infrastructure and faculty,[12] along with current curriculum ignoring industry skills, defined career paths, and evolving technologies.[13] Thus, organizations are compelled to spend significantly in making fresh talent “employable”.

While India has a decent pool of highly qualified low-cost engineers and scientists,[14] they are unwilling to work in the public sector due to limited opportunities and low growth potential,[15] where most defence R&D is undertaken. As the departure of 132 scientists in the last five years from DRDO shows,[16] even those employed mostly do not continue long-term due to better opportunities elsewhere.[17] The contribution of most of these scientists has been limited to the production of academic articles,[18] which hasn’t seen any significant and meaningful absorption in the policy. Therefore, the policy has been unable to capture the huge latent employment potential in this sector.[19]

This position must be contrasted against global competitors like the US and China, where the highly skilled and employable workforce is significantly and routinely absorbed into the most impactful R&D organization, whether private or public.[20] Moreover, unlike other leading countries, India lacks any training and education infrastructure specialized for R&D personnel in the defence sector. These countries have developed specialist defence schools that have managed to produce large pools of exclusive talent. France itself has managed to produce 134,000 specialist employees.[21]

At the procurement level, the asset acquisition process is not tasked to a dedicated cadre of the workforce.[22] Further, there are no educational or training programs for employees involved in this process.[23] Thus, there is the loss in terms of the benefits of specialization, especially in a sector where progress is characterized by specialization.

- Limited Involvement of the Private Sector

There is a significant lack of incentive for greater private sector involvement. The private sector is commercially motivated to establish its manufacturing base only when it has a good chance, or preferably guarantee, of getting frequent and sizeable orders.[24] However, the current manufacturing and procurement process has ignored this motivation but is also completely converse to it.

As the BJP government’s Rafale fiasco indicates, the procurement processes lack transparency, and frequently fraught with allegations and counter-allegations.[25] This disincentivizes both domestic and global private sector players from conducting business.

Despite unprecedented inclusion of the private sector, it is widely believed in the private sector that the government is biased towards public sector undertakings, denying a level-playing field for the private sector and even denying opportunities to bid.[26]

The government’s Strategic Partnership Model, aimed at inviting world-class defence giants to collaborate with Indian entities, has unduly restricted autonomy. Under this program, the government chooses the Indian partner for the foreign OEM, without consulting them.[27] Global defence giants, like Airbus, Lockheed Martin, ThyssenKrupp, and Dassault, have shown interest in contracting with the Indian private sector.[28] However, it is a combination of these factors that this interest has largely failed to materialise into successfully concluded deals.

Even where, despite these disincentives, the private sector has been involved, this has been in non-critical and less required areas. Most of India’s defence imports are in the category of major platforms such as fighter aircraft, helicopters, naval guns, and anti-submarine missiles.[29] However, the private sector initiatives are predominantly in the category of ammunitions (including rockets and bombs), and surveillance and tracking systems.[30]

- Evaluating ‘Transfer of Technology’

There has been no transfer of technology (“ToT”) in the critical defence procurement process. All major contracts under MII have been “off the shelf”, and without any crucial ToT.[31] As per the CAG Report, between 2007 and 2018, the government concluded 46 offset contracts but failed to implement the ToT agreements in any of them.[32]

The failure here can be attributed to successive governments unduly hoping that India’s status as a large arms importer would necessarily make international players compliant as regards sharing their intellectual property (“IP”). While foreign companies have shown interest in contracting with Indian players, the large purchase orders have been inadequate to incentivize foreign players to share their IP.[33]

The government has also been overly ambitious of ToT as a means of technology upgradation. Even implementing the negotiated ToT is not the end because the more challenging issues of absorption of this technology and ownership of IP remain.[34] Moreover, the ToT route provides India only with the ‘know-how’, without any insight into the ‘know-why’.[35] As India’s acquisition of the Sukhoi Su-30 has shown, the public sector is critically dependent on the OEMs, here the Russians, for even minor systemic upgradations.

Way Forward

The government must increase allocation to defence R&D to at least 10% and must incentivize greater contributions from the private sector. Existing capabilities and services at training and diploma centres must be upgraded through public-private partnerships. There must be a separate and devoted institutional structure for all procurement-related functions. The procurement policy must also aim at buying talent, besides technology, to bridge technology gaps. The education curriculum at engineering universities needs to be modernized, with a focus on employability. Specialist defence schools must also be established. However, it is most important that the public sector aims at retaining its talent through unique and lucrative incentive structures.

To incentivize the private sector through minimum order guarantees, the government must utilize ‘public procurement of innovation’. Under this policy tool, the government uses its exchequer to artificially generate demand for an emerging innovative solution, unavailable on a commercial scale.[36] The private sector can further be incentivized by streaming the procurement and dispute resolution process. As for procurement, a fast-track procedure with single-window clearances can be adopted.[37] As for dispute resolution a permanent arbitration tribunal must be established to expeditiously settle disputes with finality.[38]

Conclusion

Firstly, the indigenous efforts at technology up-gradation have failed due to limited R&D output, shortage of skilled workforce, and limited private sector involvement. The R&D budgetary allocation is way below the recommended and global standard. The shortage of skilled workforce is both at the research and procurement due to a lack of education and training infrastructure specific to the defence sector, low employability among most graduates, and unwillingness to work in the public sector among highly qualified graduates. The private sector has been disincentivized due to a lack of order guarantees, the unrealistic and retroactive manner of the procurement process, the constant allegations and counter-allegations, and the continued bias towards the public sector. Moreover, the private sector has been involved in non-critical and less required areas.

Secondly, while the government has concluded ToT agreements, it has been inefficient in enforcing them. Moreover, even if this were to succeed, it has not established any action plan for absorbing this technology and addressing ownership of IP. It has also been overly ambitious of the utility of ToT.

References

[1] Kuldip Singh, ‘Yes, Indian Military Can Go the ‘Make in India’ Way – Just Not Yet’ (The Quint, 25 May 2020) <https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/india-armed-forces-defence-sector-military-expenditure-budget-technology-upgrade-make-in-india> accessed 19 December 2020.

[2] Arjun Srinivas, ‘Private defence business gets one more nudge’ (LiveMint, 1 October 2020) <https://www.livemint.com/news/india/private-defence-business-gets-one-more-nudge-11601460654397.html> accessed 19 December 2020.

[3] Snehesh Alex Philip, ‘China has become a major exporter of armed drones, Pakistan is among its 11 customers’ (The Print, 23 November 2020) <https://theprint.in/defence/china-has-become-a-major-exporter-of-armed-drones-pakistan-is-among-its-11-customers/549841/> accessed 4 January 2021.

[4] Rajan Kochhar, ‘Preparing defence sector for post COVID-19 world: Time to treat private sector as equal partner’ (Economic Times, 5 May 2020) <https://government.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/governance/opinion-make-in-india-a-dream-or-reality-for-the-armed-forces/75552970> accessed 19 December 2020.

[5] Jayant Singh, ‘Industry Scenario’ (Invest India) <https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/defence-manufacturing> accessed 19 December 2020.

[6] Prof (Dr) SN Misra, ‘Make in India: Challenges Before Defence Manufacturing’ (2015) 30(1) Indian Defence Rev <http://www.indiandefencereview.com/news/make-in-india-challenges-before-defence-manufacturing/2/> accessed 19 December 2020.

[7] ‘Government Expenditures on Defence Research and Development by the United States and Other OECD Countries: Fact Sheet’ (2020) Congressional Research Service R45441 <https://fas.org/sgp/crs/natsec/R45441.pdf> accessed 19 December 2020; A Sivathanu Pillai, ‘Defence R&D’ in Vinod Misra (ed), Core Concerns in Indian Defence and the Imperatives for Reforms (Pentagon Press & IDSA 2015) 132-133.

[8] Misra (n 6).

[9] Amitabha Pande, ‘Defence, Make in India and the Illusive Goal of Self Reliance’ (The Hindu Centre for Public Policy, 11 April 2019) <https://www.thehinducentre.com/the-arena/current-issues/article26641241.ece> accessed 19 December 2020.

[10] Azhar Shaikh, Dr. Uttam Kinange, & Arthur Fernandes, ‘Make in India: Opportunities and Challenges in the Defence Sector’ (2016) 7(1) Intl J Research in Commerce & Management 13, 14-15.

[11] Kishore Jayaraman, ‘How Can India Bridge The Skill Gap in Aerospace & Defence Sector?’ (All Things Talent, 24 September 2018) <https://allthingstalent.org/2018/09/24/how-can-india-bridge-skill-gap-in-aerospace-defence-sector/> accessed 30 December 2020.

[12] Dr. JP Dash & BB Sharma, ‘Skilling Gaps in Defence Sector for ‘Make in India’’ (2017) 32(2) Indian Defence Rev <http://www.indiandefencereview.com/spotlights/skilling-gaps-in-defence-sector-for-make-in-india/> accessed 30 December 2020.

[13] Jayaraman (n 10); Dhiraj Mathur, ‘Unlocking defence R&D in India – Do we have the skill?’ (Firstpost, 6 April 2016)<https://www.firstpost.com/business/unlocking-defence-rd-in-india-do-we-have-the-skill-2715650.html> accessed 30 December 2020.

[14] Mathur (n 13).

[15] PR Sanjai, ‘Indian aerospace sector needs one million skilled workforce in next 10 years’ (Livemint, 20 February 2015) <https://www.livemint.com/Politics/hRJQjq7ZKVXQ5RFkzWbmAJ/Indian-aerospace-sector-needs-one-million-skilled-workforce.html> accessed 30 December 2020.

[16] PTI, ‘132 scientists left DRDO on personal grounds in last 5 years: Govt’ (Economic Times, 12 March 2020) <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/defence/132-scientists-left-drdo-on-personal-grounds-in-last-5-years-govt/articleshow/74579857.cms?from=mdr> accessed 30 December 2020.

[17] Dash (n 12).

[18] PTI, ‘India is world’s third largest producer of scientific articles: Report’ (Economic Times, 18 December 2019) <https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/science/india-is-worlds-third-largest-producer-of-scientific-articles-report/articleshow/72868640.cms?from=mdr> accessed 30 December 2020.

[19] ‘Make in India: An Overview of Defence Manufacturing in India’ (2015) Singhania & Partners LLP Report <https://www.gita.org.in/Attachments/Reports/Make-in-India-Defence-Manufacturing-in-India.pdf> accessed 19 December 2020.

[20] Ranjit Ghosh, ‘Defence Research and Development: International Approaches for Analysing the Indian Programme’ (2015) IDSA Occasional Paper 41, 11-34 <https://idsa.in/system/files/opaper/OP41__RanjitGhosh_140815.pdf> accessed 19 December 2020.

[21] Dash (n 12).

[22] Shaikh (n 10) 15.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Rohit Srivastava, ‘New measures for self-sufficiency in defence – industry perspective’ (Indian Defence Industries, 19 May 2020) <https://indiandefenceindustries.in/defence-reforms-industry-perspective> accessed 19 December 2020.

[25] Pradip R Sagar, ‘How ‘Make in India’ in defence sector is still an unfulfilled dream’ (The Week, 25 May 2019) <https://www.theweek.in/theweek/current/2019/05/25/how-make-in-india-in-defence-sector-is-still-an-unfulfilled-dream.html> accessed 19 December 2020.

[26] Ibid; Lt. Gen. (Retd.) (Dr). Subrata Saha, ‘Execution key for defence manufacturing in India’ (LiveMint, 2 April 2020) <https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/Gx9NVPGvIsVbVzLTJ0VouK/Execution-key-for-defence-manufacturing-in-India.html> accessed 19 December 2020.

[27] Prasanna Karthik, ‘India’s strategic partnership policy is counter-productive in its current form’ (Observer Research Foundation, 8 June 2020) <https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/indias-strategic-partnership-policy-is-counter-productive-in-its-current-form-67511/> accessed 19 December 2020.

[28] Sagar (n 25).

[29] Srinivas (n 3).

[30] Ibid.

[31] Singh (n 1); Sagar (n 25).

[32] Joe C Mathew, ‘Defence offset policy performance dismal: CAG’ (Business Today, 24 September 2020) <https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/defence-offset-policy-performance-dismal-cag/story/416872.html> accessed 19 December 2020.

[33] Lieutenant Commander L Shivaram (Retd), ‘Understanding ‘Make in India’ in the Defence Sector’ (2015) 145(601) J United Service Institution of India <https://usiofindia.org/publication/usi-journal/understandingmake-in-india-in-the-defence-sector/> accessed 19 December 2020.

[34] Lt Gen A B Shivane, ‘India needs outcome oriented defence reforms’ (Indian Defence Industries, 22 May 2020) <https://indiandefenceindustries.in/india-outcome-oriented-reforms> accessed 19 December 2020.

[35] Misra (n 6).

[36] E. Uyarra & J. Edler, ‘Barriers to Innovation through Public Procurement: A Supplier Perspective’ (2014) 34(10) Science Direct <https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166497214000388> accessed 19 December 2020.

[37] Kochhar (n 4).

[38] Lt. Gen. (Retd.) Dalip Bharadwaj, ‘‘Make in India’ in defence sector: A distant dream’ (Observer Research Foundation, 7 May 2018) <https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/make-in-india-defence-sector-distant-dream/> accessed 19 December 2020.

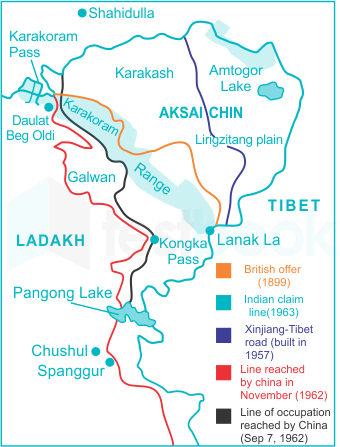

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.

The opening skirmish of that conflict occurred in the North East with the capture, on 8th Sept, of the isolated Assam Rifles post at Dhola, on the southern slopes of the Thag La ridgeline. This post was surrounded and completely dominated by PLA positions on higher ground, and its loss was a foregone conclusion. The actual conflict commenced at approximately 0500 hours on 20th October, when the PLA launched a massive infantry attack, supported by artillery, on the 7 Infantry Brigade positions. The Brigade was deployed in a tactically unsound manner on direct orders of GOC 4 Corps, Lt Gen B M Kaul, along the Southern banks of the Namka Chu River over a 20 Km frontage instead of on the heights overlooking the river.