TPF Occassional Paper – 01/2025

Between Western Eurocentric Universalism and Cultural Relativism: Mutual Recognition of the Civilisations of the Earth as precondition for the Survival of Mankind

Andreas Herberg-Rothe

In the 19th century, the Europeans conquered the whole world; in the 20th century, the defeated nations and civilizations had to live with the victorious West; in the 21st century, the civilizations of the earth must finally learn to live together.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights was codified by the United Nations in 1948. But the academic debate on the universality of the norms on which it is based is far from over. The question remains whether there are universal values other than those of the West. Western values alone are often implicitly regarded as universal. But whether this is scientifically justifiable is more than debatable. At the same time, few participants in the debate seriously doubt the need for universal human dignity.

In the current debate, the binary positions of relativism and universalism are in a stalemate. A way out of this dichotomy would have to withstand the charge of ethnocentrism as well as particular relativism. Neither should dimensions of power and colonialism be ignored, nor should inhumane practices such as torture, humiliation and sexual violence be relativised by reference to another ‘culture’. If a universal approach is to be found, it should not be implicitly Westernised. This is a criticism of existing approaches, particularly in postcolonial theory.

Historically, ethnocentrism, as a mere description of a state of affairs, has developed into a justification of ‘cultural superiority’ and, as a consequence, of oppression and exploitation.

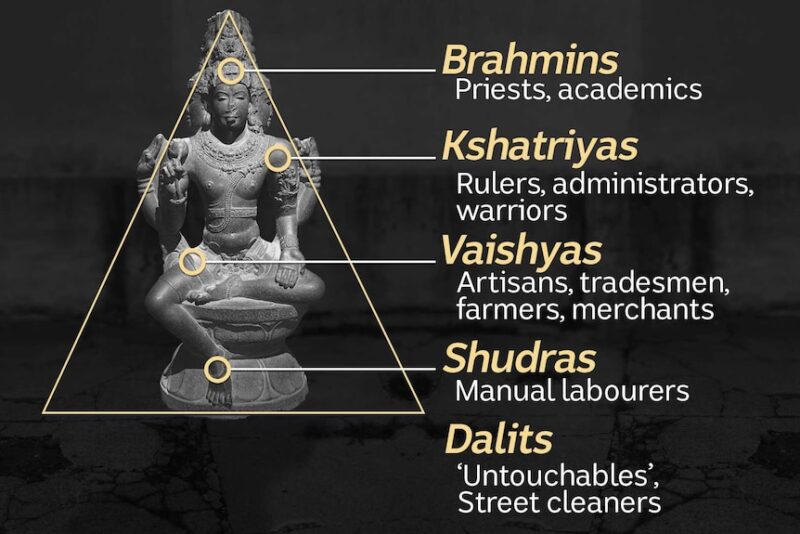

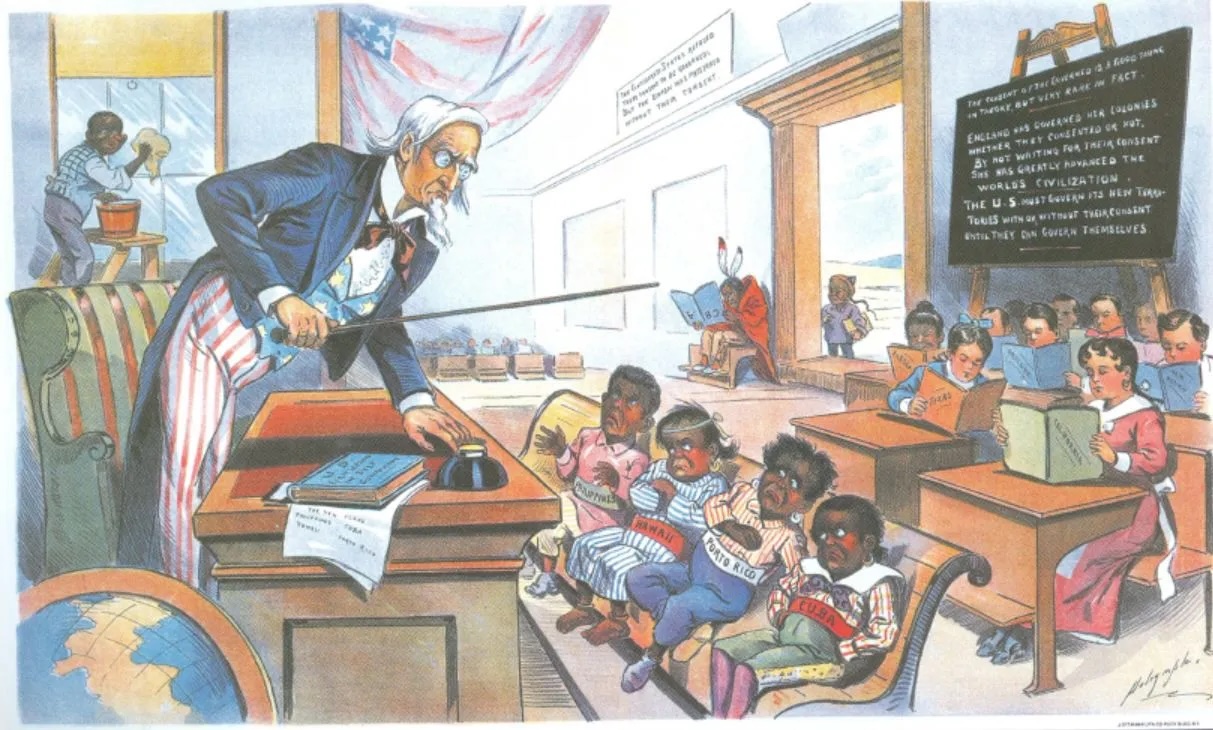

It is about the justifiability of universal norms on the one hand, and the inevitability of particular justifications of norms on the other. Historically, ethnocentrism, as a mere description of a state of affairs, has developed into a justification of ‘cultural superiority’ and, as a consequence, of oppression and exploitation. An initially unconscious preference for and belief in one’s own (cultural) perspective, the unquestioned truth and correctness of one’s own norms, values and patterns of behaviour, did not develop into ‘live and let live’. This form of ethnocentrism rejects the acceptance of cultural differences and represents an attitude that legitimises the destruction of the foreigner as a legitimate consequence of one’s own superiority. This, of course, refers mainly to the long-standing colonisation of supposedly ‘inferior’ peoples by European states and the associated cultural appropriation and cultural destruction or exploitation. These practices were morally legitimised on the basis of the conviction that one’s own way of life was superior to all other ways of life, not only militarily and politically, but also cognitively and morally. Ideologically, this argument is based on various elements, including the proselytising idea of the Christian message of salvation, the idea of the ‘progress’ of Western civilisation over other cultures and the idea of ‘racial doctrine’.

In reaction to this unreflected, chauvinistic ethnocentrism, two main currents of contradiction developed: universalism and relativism. Universalism ‘assumes that it is possible to find standards of value that apply across cultural boundaries and are universally valid’, while the relativist position, in the absence of the possibility of an ‘extra-cultural’, objective judgement of a situation, all cultures, with everything that belongs to them, are ascribed the same value.

Universalism

The argumentative basis of Western universalism is the assumed fundamental equality of all human beings – both in their intellectual capacity (cognitive) and in their materiality (normative), which leads to a general insight into certain universal norms. The most obvious example of this is universal human rights, whose need for universality is clear from their very name.

The cognitive premise of this kind of universalism goes back to the Enlightenment and the idea that all human beings have, in principle, the same cognitive capacities, even if they differ in individual cases. Only on this basis can the premise of normative universalism in the Enlightenment be realised. But this leads to various problems, paradoxes and points of criticism, because this conception is based on a particular understanding of rationality that is rooted in the thinking of Western modernity. For example, it excludes any kind of holism, although this conceptualisation is by no means irrational, but represents a different kind of rationality.

The apparent paradox of the uniqueness of each culture lies in the claim to universality that all cultures are of equal value. We can therefore speak neither of a universalism that is purely independent of culture, nor of a norm that can be attributed to only one culture.

One frequently pursued solution to the tension between universal norms, which nonetheless originate in only one culture, and different culturally determined norms has been to search for what is common to all cultures. This approach, which in itself goes further, was pursued above all in the project of the ‘global ethic’, which sought the common foundations of all religions. Western modern universalism had thus abandoned its claim to all-encompassing universality and limited itself to a kind of ‘core norms’. Instead of questioning specific cultural practices, the focus is on the fundamental premises of human coexistence. In my view, this project was doomed to failure after the initial euphoria, because the commonalities were based on an ever-increasing abstraction. This leads to two fundamental difficulties: the unresolved problem of drawing boundaries between different forms of norms, and the justification of particular norms on the basis of the universal assumption that all cultural norms are in principle equal. The apparent paradox of the uniqueness of each culture lies in the claim to universality that all cultures are of equal value. We can therefore speak neither of a universalism that is purely independent of culture, nor of a norm that can be attributed to only one culture.

Strong normative relativism represents a ‘normative statement that all normative systems are fully justified in their diversity’ – a paradox since this is a statement with a claim to universal validity. In contrast, weak normative relativism is derived from the impossibility of universally valid normative statements, which merely means a ‘non-evaluability’ of normative systems The demarcation between concrete social norms is therefore very difficult

Because of the difficulty of justifying strongly normative positions, ‘differentiated’ theories of relativism argue from a ‘weakened position’, albeit at the expense of unambiguity due to the lack of demarcation. Culture is then understood as ‘dynamic and hybrid’, while ‘normative overlaps’ are recognised without doubting the fundamental relativity of all norms.

Paradoxical structure

Relativism does not provide a ‘ground zero’ from which to make generally valid statements – this rules out the possibility of relativism being universally valid in itself, as well as the possibility of relativism being regarded as a ‘universal truth’. Relativism cannot, therefore, justify itself out of itself, which it has in common with other theoretical currents in the age of postmodern critique (Herberg-Rothe 2025). Moreover, it does not necessarily apply universally, but can be limited in time or place: So the undecidability of normative conflicts might appear to be a particularly obvious contemporary phenomenon, without it being true for all times and places that normative conflicts are fundamentally undecidable. This concept of decidable and undecidable questions is based on the position of Heinz von Foerster’s radical constructivism. In his desperate attempt to leave behind all only apparent objectivity and the subjectivity of all norms, he resorts to a binary opposition between objectivity (in mathematics) and subjectivity.

Due to the equivalence of all cultural standpoints and the lack of presupposed values, no well-founded criticism can take place, which makes relativism normatively arbitrary in relation to itself. Neither the persecution of minorities nor discrimination can be legitimately criticised if this is seen as a cultural particularity. The norm of ‘absolute tolerance of cultural differences’ is both empirically untenable and logically inconsistent, since here too there is a claim to universal validity. However, this point of criticism already presupposes the premise of universalism that there are conditions that are worthy of criticism despite their culture-specific justification.

The observed norms and values appear to be specific responses to specific social problems but are in no way connected to the supposed ‘essence’ of a culture, as culture itself is perceived as hybrid, fluid and contradictory – instead of judging inhumane practices of one’s own culture, it is about understanding. In this context, the post-colonial reality should also be mentioned, in which there are no longer any cultures without interference.

Relativism in its weakened form has moved away from normative statements. In the absence of a judgmental dimension, it no longer makes a statement about tolerance towards certain cultural practices. The observed norms and values appear to be specific responses to specific social problems but are in no way connected to the supposed ‘essence’ of a culture, as culture itself is perceived as hybrid, fluid and contradictory – instead of judging inhumane practices of one’s own culture, it is about understanding. In this context, the post-colonial reality should also be mentioned, in which there are no longer any cultures without interference.

In order to be able to criticise on the basis of relativism in human practices despite all these objections, two possibilities need to be mentioned: 1. to establish ‘qualified norms’ without further justification in order to criticise on the basis of them, and 2. to practise a particular, culturally immanent criticism – of one’s own cultural norms on the basis of other norms of one’s own culture. For example, there are numerous culturalist justifications for gender equality, “general” human rights or democracy, which shows that a culturally immanent and particular critique of domination does not necessarily have to differ in content from a universalist critique (see for example Molla Sadra in Herberg-Rothe 2023). Both solutions are in no way ideal, because in the first attempt, we encounter a hidden enthnocentrism, and in the latter, the problem arises between contrasting norms within one culture.

Covert Westernisation and reverse Ethnocentrism

Relativism is also a theory of Western origin, which can be seen in the Western-influenced ‘idea of tolerance’ – but this point also applies mainly to a normatively strongly interpreted relativism. Inverse ethnocentrism, on the other hand, means ‘labelling everything foreign as right’.

What underlies both, universalism and relativism, is the struggle for knowledge: which norms can be taken for granted? Or, more philosophically, what can we know? Both positions have argumentative shortcomings that are not easily remedied.

Knowledge is closely linked to power (the power to define, to enforce, to disseminate or to withhold knowledge) and thus to domination and often to violence. This connection is expressed in social tensions between the legitimation of domination and the subversion of existing conditions.

The use of human rights to achieve social change raises the question of “whether this process is not itself, in terms of knowledge, a bureaucratic, almost classically ethnocentric process with an imperial claim to universality’ that spreads ‘Western culture’ and its models of action globally’.

Transnational encounters since the colonial era have steadily increased due to globalisation and require reassessment. The use of human rights to achieve social change raises the question of “whether this process is not itself, in terms of knowledge, a bureaucratic, almost classically ethnocentric process with an imperial claim to universality’ that spreads ‘Western culture’ and its models of action globally’. At the same time, this process opens up a dialogue beyond culturally determined borders, which we must be aware in order to transcend them.

How could this stalemate between ethno Universalism and cultural relativism be overcome, at least in perspective?

A new approach to practical intercultural philosophy

Intercultural philosophy can play an important role in this process of mutual recognition among the civilizations of the earth. Since Karl Jaspers, the godfather of intercultural philosophy, acknowledged the existence of four different civilizations (Holenstein 2004, Jaspers 1949), immense progress has been made in understanding the different approaches. Nevertheless, all civilizations have asked themselves the same question but have found different answers. Cross-cultural philosophy is thus possible because we as human beings ask the same questions (Mall 2014). For example, in terms of being born, living and dying, between immanence and transcendence, between the individual and the community, between our limited capacities and the desire for eternity, the relationship between us as animals and the ethics that constitute us as human beings – our ethical beliefs may be different, but all civilizations have an ethical foundation. In fact, I would argue that it is ethics that distinguishes us from animals, not our intellect (Eiedat 2013 about Islamic ethics). We may realize the full implications of this proposition when we relate it to the development of artificial intelligence.

Detour via Clausewitz

An alternative solution to the problem raised by Lyotard suggests another dialectic, as implicitly developed by Carl von Clausewitz based on his analysis of attack and defence. The approach of Clausewitz is insofar of paramount importance because it presupposes neither a primacy of identity in relation to difference, contrast, and conflict, nor to the reverse as in the conceptualizations of the post-structuralists (Herberg-Rothe 2007, Herberg-Rothe/Son 2018) or the adherents of a purified Western modernity in the concepts of Habermas and Giddens. In contrast to binary opposites, Clausewitz’s model of the “true logical opposition and its identity,” a structure-forming “field” (something like a magnetic field) allows us to think of manifold mediations as well as differences between opposites. If we formulate such an opposition in the framework of a two-valued logic (which formulates the opposition with the help of a negation or an adversarial opposition), there is a double contradiction on both sides of the opposition. From the assumption of the truth of one pole follows with necessity the truth of the other, although the other formulates the adversarial opposition of the first and vice versa. Hegel’s crucial concepts such as being and nothingness, coming into being and passing away, quantity and quality, beginning and ending, matter and idea are such higher forms of opposition which, when determined within the framework of a two-valued logic, lead to logical contradictions. Without taking into account the irrevocable opposites and their unity, a “pure thinking of difference” leads either to “hyper-binary” systems (such as the relation of system and lifeworld, of constructivism and realism) or to unconscious absolutizations of new mythical identities (such as Lyotard’s notion of plasma as well as Derrida’s chora).

Clausewitz’s “true logical opposition” and its identity enables the thinking of a model in which the opposites remain irrevocable, but at the same time, in contrast to binary opposites

- both remain in principle equally determining; this model is therefore neither dualistic nor monistic, but cancels this opposition in itself and sets it anew at a new level.;

- structure a “field” of multiple unities and differences;

- enable a conceptualization, in which the opposites have a structure-forming effect, but do not exist as identities detached from one another,

- and in which there are irrevocable boundaries between opposites and differences, which at the same time, however, are historically socially distinct. The concrete drawing of boundaries is thus contingent, without the existence of a boundary as such being able to be abolished (Herberg-Rothe 2007, 2019 and Herberg-Rothe/Son 2018). Clearly, in the, albeit limited, model of a magnet neither the south nor north pole exists as identity, a (violent) separation between both even leads to a duplication of the model. At the same time, both poles are structures forming a magnetic field, without a priority for either side. And finally, Clausewitz’s model of the true logical opposition goes beyond the one of polarity, because it additionally allows us to think of manifold forms of transitions from one pole to the other (Herberg-Rothe 2007, Herberg-Rothe/Son 2018).

This conception of an “other” dialectic is also the methodological precondition of thinking “between” Lyotard and Hegel (Herberg-Rothe 2005). It treatises above all categories such as mostly asymmetrical transitions and reversals as well as the “interspace” (Arendt) between opposites. With such an understanding of dialectics, it is possible to understand the apparent contradiction between the rejection of the highest meta-meta-language and the fact that the language used in this critique, theory, is itself this actually excluded “highest” level of language, not as a logical contradiction, but as a performative one. Such performative contradictions between what a proposition, statement, etc., says and what it is are at the heart of Hegel’s notion of dialectic. Of all things, Hegel’s criticized and rejected form of dialectic makes it possible to conceive of these contradictions not as “logical” ones, but as ones that ground, but also force, further development as distinct from mythical ways out. This form of dialectic, however, contains at the same time the demonstration of a principle of development without conclusion and thus puts Hegel’s “great logic” as “thoughts of God before the creation of the world” in its place (Hegel Preface to the Science of Logic, Wdl I, Werke 5). Nevertheless, these performative contradictions should also not be absolutized, they are just one aspect of a different dialectics.

Although I advocate the development of an intercultural philosophy as part of transnational governance and mutual recognition among the civilizations of the earth, I would like to highlight the main problem, at least from my point of view. Aristotle already asked the crucial question of whether the whole is more than the sum of its parts. If I understand Islamic philosophy correctly, it starts from the assumption that the whole is indeed more than the sum of its parts – one could call this position a holistic approach (Baggini 2018). In contrast, Western thought is characterized by the approach of replacing the whole precisely by the sum of its parts. We might call this an atomistic approach – only the number of electrons, neutrons, distinguishes atoms etc. In terms of holism, I would argue that the task might be to distinguish the whole from mere hierarchies – in terms of the concept of harmony in Confucianism, I would argue that true harmony is associated with a balance of hierarchical and symmetrical social and international relations. Instead of the false assumption in Western approaches that we could transform all hierarchical relationships into symmetrical ones, we need to strike a balance between the two. Harmony does not mean absolute equality in the meaning of sameness but implies a lot of tension. Harmony can be characterized by unity with difference, and difference with unity, as already mentioned (Herberg-Rothe/Son 2018). I sometimes compare this perspective to a wave of water in a sea: if there are no waves, the sea dies; if the waves are tsunamis, they are destructive to society.

I start from the following fivefold distinction of thinking, based on the fundamental contrasts of life (while Baggini 2018 and Jaspers 1949, for example, reduce different ways of thinking largely to the development of functional differentiation).

- Attraction and repulsion, closeness and distance, equality and freedom, love and hate,

- Beginning and ending (birth and death, finiteness – infinity),

- Happiness and suffering (in Greek and Indian philosophy

- Part-whole (individual-community, immanence-transcendence, holism-hierarchies).

- Knowledge (experience, positive sciences, extended sense impressions,

and method – mathematics and logic) versus feeling/the concept of intuition, belief.

The listed methodological approaches try to cope with unity and opposition. In my opinion, they are also necessary approaches and can be seen as differentiations within the idea of polarity.

Differentiations in thinking

- Either – or systems, = Western modern thought, concentration on the method (since Descartes and Kant, Vienna Circle, Tarski), democracy, individualism, in Islam Ibn Sina and Ibn Khaldun, in Chinese thought the tradition of Han Fei and Li Se; Yan 2011, Zhang 2012).

- As well as – Daoism, early Confucianism, but also New Age approaches, Heißenberg’s uncertainty principle, and dialectics.

- Neither-Nor enables the construction of “being-in-between”; Plato’s metaxis plus Indian logic, the whole concept of diversity, difference thinking, de-constructivism, the post-structuralism, post-colonialism

- system thinking, structuralism – here I struggle with the distinction between holism (in the Islamic worldview) and pure hierarchies (in Islam Al Ghazali); inherent logic of systems (Luhmann) and functional differentiation; in Eastern philosophies, we find this approach mainly in highlighting spiritual approaches

- process thinking – in ethics this can be found e.g. in utilitarianism, stage theories (Piaget, Kohlberg; Hegel’s world history as the progress of freedom consciousness), Hegel’s becoming at the beginning of his “logic” as “surplus” of coming into being and passing away; cycle systems; enlightenment; Dharma religions, in China, Mohism.

While there are probably already worked out methods for points 1, 4 and 5, I lack such for 2 and 3, which are always in danger of expressing arbitrariness. This becomes especially clear in the mysticism of the New Age movement.

How can this fivefold distinction be derived from one model, which is not a totalizing approach (Mall 2014)? For this purpose I use again the simplified model of polarity. This method is elaborated in my Clausewitz interpretation of his wondrous trinity and the dialectic of attack and defense (Herberg-Rothe 2007 and 2019).

Differences in polarity as a unifying model.

- Either-Or systems: Each of the two poles is either a north or a south pole (= tertium non datur). We find those approaches in mathematics, logic, rationality and methods in general; such conceptualizations are also to be found in zero-sum games – what one side gains, the other loses (rationality, if then Systems, in Cina Lli Si and Han Fei);

- As well As (earlier Confucius, Daoism): the magnet as unity consists of the opposites of both poles and the magnet “is” both north pole and south pole. This is analyzed in detail in my Clausewitz interpretation on the basis of war as unity and irrevocable opposition of attack and defence. We find this thinking, especially in Chinese ideas of win-win solutions. Here, competition and conflict in one area do not exclude cooperation in another (Herberg-Rothe 2007, Chinese version 2020.)

- Neither North nor South pole exist as identities (Plato’s metaxis, Indian thought) – they are rather dynamic movements in between the opposites (see in detail again Clausewitz’s concept of attack and defense; this understanding is the methodological basis of diversity; Herberg-Rothe 2007; see the French theorists of post-structuralism).

- Structure (system theories, Islamic holism): North pole and south pole “construct” a magnetic field outside and inside the materiality of the magnet, a non-material structure.

- Process thinking: Here the simplified example of the magnet finds its end – but can be understood beyond the physical analogy easily as movement from the south pole to the north pole and “always further” (sine curve on an ascending x-axis). In this sense, Already Hegel had considered the discovery of polarity as of infinite importance but criticized it because in this model the idea of transition from one pole to the other was missing (Herberg-Rothe 2000 and 2007). Molla Sadra (1571-1636), the most important philosopher of the School of Isfahan, elaborated this progressive circular movement particularly clearly. Although he is mainly regarded as an existential philosopher who denies any essence, he actually postulated a kind of progressive circle as the decisive essence (for an overview see Yousefi 2016, for more details see Rizvi 2021).

A unifying model – Virtuous Concentric Circles

Starting from the premise that Western thinking is shaped by the billiard model of international relations and that of all other civilizations by concentric circles and cycles (Herberg-Rothe/Son 2018), the aim is to work out how extensively both models determine our thinking in the respective cultural sphere in order to develop a perspective that includes both sides. In doing so, I do not assume one-dimensional causes for violent action, nor do I assume pure diversity without any explanation of causes. Instead, I work in perspective with virtuous and vicious circles – in these circles, there are several causes, but they are not unconnected to each other but are integrated into a cycle. So far, this methodological approach has probably been applied mainly in the Sahel Syndrome. The methodological approach would involve trying to break vicious circles and transform them into virtuous circles – this is where I would locate the starting point of a new approach to intercultural philosophy.

Ideally, a virtuous circular perspective would look like this:

- Understanding of discourses on how conflicts with cultural/religious differences are justified/articulated.

- Attribution of these differences to different concepts of civilization.

- Mutual recognition of the same issues in different ways of thinking.

- Self-knowledge not only as religion or culture, but as a civilization.

- the self-commitment to one’s own civilizational standards, norms (Jaspers 1949 and Katzenstein 2009) etc., which can also contribute to the management of intra-societal and international conflicts.

At the infinite end of this process would be a kind of mutual recognition of the civilizations of the earth, accompanied by their self-commitment to their own civilizational norms. My colleague Peng Lu from Shanghai University has made the following suggestion: In the 19th century, the Europeans conquered the whole world; in the 20th century, the defeated nations and civilizations had to live with the victorious West; in the 21st century, the civilizations of the earth must finally learn to live together. This is in my view the task of the century. Solving the problem of ethno-universalism and cultural relativism has nothing to do with wishful thinking, but is the precondition for the survival of humankind in the twenty-first century, unless we want to repeat the catastrophes of the twentieth century on a larger scale.

References:

Baggini, Julian (2018), How the World Thinks. A global history of philosophy. Granta: London.

Clausewitz, Carl von (2004) On War. Edited and translated by Michael Howard and Peter Paret. Princeton: Princeton University Press

Fukuyama, Francis (2018), Against Identity Politics. The new tribalism and the crisis of democracy. In Foreign Affairs, Sept./Oct. Retrieved from: https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/americas/2 018-08-14/against-identity-politics; last accessed, Oct. 3, 2018, 10.21.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2003/2017), Der Krieg. 2nd ed., Campus: Frankfurt.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas and Son, Key-young (2018), Order wars and floating balance. How the rising powers are reshaping our worldview in the twenty-first century. Routledge: New York.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2023) Toleration and mutual recognition in hybrid Globalization. In: International Studies Journal, Tehran, Print version: September 2023; Volume 20, Issue 2 – Serial Number 78; pp 51-80.

Also published Online: URL: https://www.isjq.ir/article_178740.html?lang=en; last access 4.11. 2023.

Herberg-Rothe, Andreas (2024), Lyotard versus Hegel. The violent end of postmodernity. In: Philosophy and Sociology. Belgrade 2024/2025 (forthcoming)

Jaspers, Karl (1949), Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte. Munich: Piper 1949 (numerous follow-up editions).

Katzenstein, Peter J (2009). Civilizations in World Politics. Pluralist and pluralist perspectives. Routledge: New York

Li, Chenyang (2022), “Chinese Philosophy as a World Philosophy”. In: Asian Studies, September 2022, pp. 39-58.

Yan, Xuetong. Ancient Chinese thought, modern Chinese power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Zakaria, Fareed (2008), The Post-American World, New York/London: W. W. Norton, 2008.

Zhang, Wei-Wei (2012), The China Wave: Rise of a Civilizing State. Hackensack: World Century Publishing Corporation.

Feature Image Credit: www.ft.com

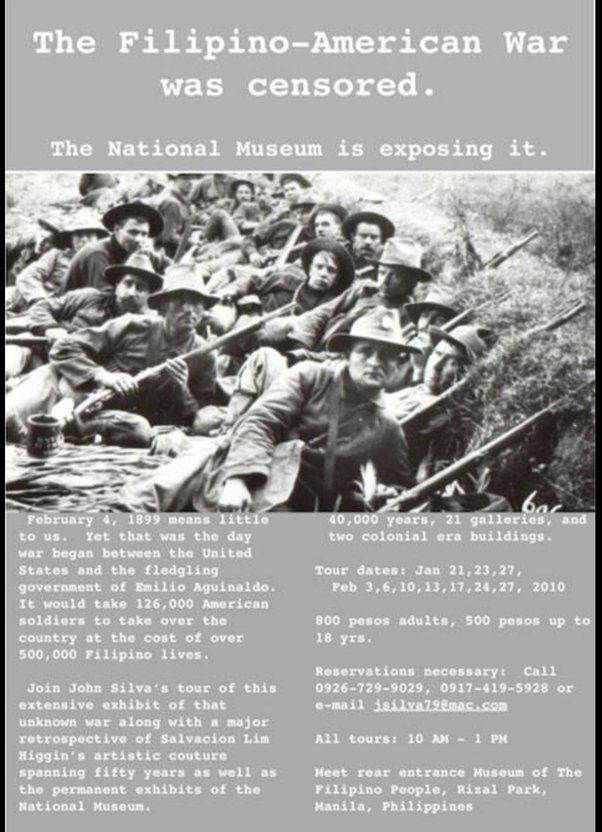

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

The Philippines, a twice-colonized archipelago that achieved its complete independence in 1946, is a member of the ASEAN and an essential player in the geopolitics of the Southeast Asia region. Its status is owed mainly to its rapidly growing economy, of which the services industry is the most significant contributor, comprising 61% of its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (Bajpai, 2022). Services refer to various products – for example, business outsourcing, tourism, and the export of skilled workers, healthcare workers, and labourers in other industries. In recent years, a growing demand for qualified professionals has grown as the economy has grown, thus necessitating more robust educational systems (Bajpai, 2022). Although the Philippines has a high literacy rate, hovering at around 97%, the efficacy of its educational system is often called into question (“Literacy Rate and Educational Attainment”, 2020). Administration oversight, infrastructural deficiencies, and pervasive corruption in the government that seeps into the entities responsible for educational reform are significant issues that legitimize these doubts (Palatino, 2023). However, reforming the current flaws in the system requires an understanding of the basic underlying structure of the country’s educational system as it is today. This fundamental understanding can help clarify specific political trends in the status quo and highlight the importance of proper historical education in developing a nation. Despite its ubiquity in nearly every curriculum, the study of history as a crucial part of the education system is often not prioritized, leading to an underdeveloped understanding of the society’s culture and previous struggles with colonial exploitation. Though it is present in the Philippines’ education today, it continues to change because of its historically dynamic demographic and political atmosphere.

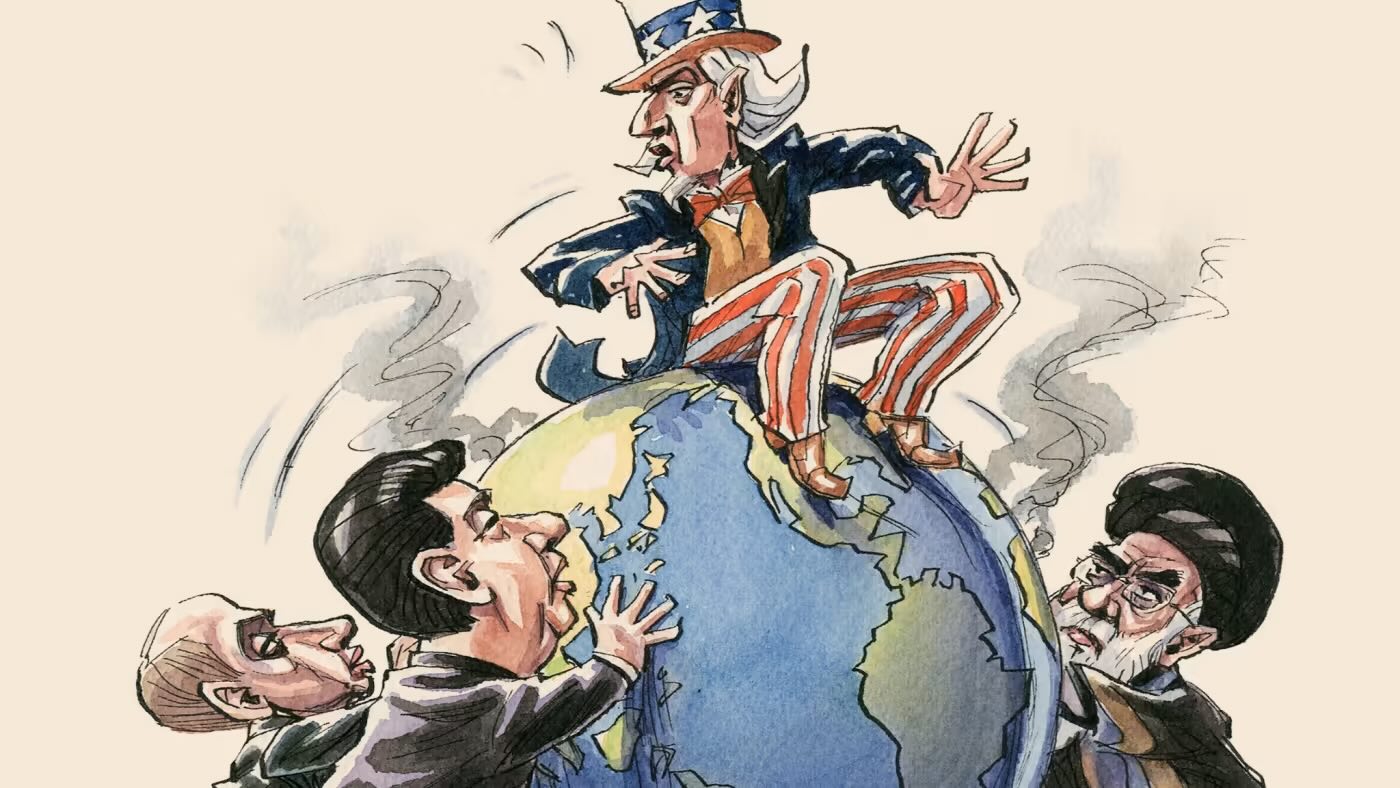

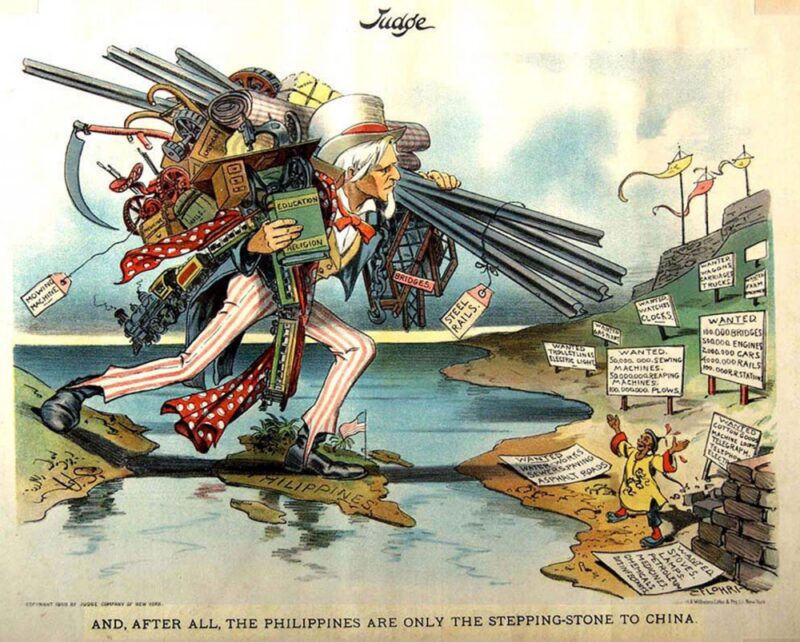

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.

Uncle Sam, loaded with implements of modern civilization, uses the Philippines as a stepping-stone to get across the Pacific to China (represented by a small man with open arms), who excitedly awaits Sam’s arrival. With the expansionist policy gaining greater traction, the possibility for more imperialistic missions (including to conflict-ridden China) seemed strong. The cartoon might be arguing that such endeavours are worthwhile, bringing education, technological, and other civilizing tools to a desperate people. On the other hand, it could be read as sarcastically commenting on America’s new propensity to “step” on others. “AND, AFTER ALL, THE PHILIPPINES ARE ONLY THE STEPPING-STONE TO CHINA,” in Judge Magazine, 1900 or 1902.