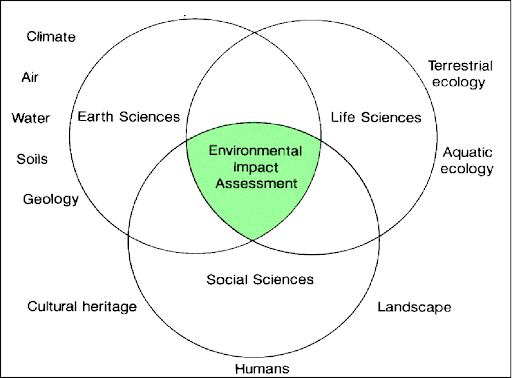

Amidst the first nationwide Covid-19 emergency lockdown, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change [MoEF&CC] published the draft Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) notification 2020 to replace the earlier 2006 notification under the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986. EIA is a process to estimate the overall environmental impacts of projects by taking into consideration the views of the people to decide whether the proposed project is approved for operation. Implementation of EIA is a form of control over the exploitative malpractices of private players while at the same time, it could also form a prerequisite for grants and loans by various international financing institutions.

The major flaw with the previous EIA which even the current draft failed to fix was its low integration with other frameworks of ecological governance and public policy.

Commonly the EIA has an entire process of reporting depending on the country and the industry. India follows four major steps in this process: scoping (issuing terms of reference), preparation of the report, public consultation, final expert appraisal. The major flaw with the previous EIA which even the current draft failed to fix was its low integration with other frameworks of ecological governance and public policy. The argument of rent-seeking, red-tape bureaucracy, delay in clearance were legitimate criticism by the current government and developers when we look into the number of scattered amendments made to EIA 2006.

However, the aim of making the new draft more transparent and pragmatic was proposed through the removal of several activities from consultation and granting post-facto approval. It dismantles the notion of prior clearance from expert committees based on the categorization (A, B1 and B2), construction project size (built-up area up to 150,000 sq. m), reduction in monitoring period (from every 6 months to once a year), exemptions to ‘strategic’ programs and ‘border regions’ all of which were set arbitrarily (Gupta 2020). Reducing the notice period for a public hearing from 30 days to 20 days further dilutes the effectiveness.

While massive online protests, public feedbacks and petitions ensued, there were cases of websites blocked by filing Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) to few environmental groups such as ‘Fridays For Future’ and others

Additionally, the possibility of granting resumption through remediation of ecological damage based on assessment goes against the precautionary principle of avoiding environmental harm. The notification also excludes reporting public violations, instead only reports by government and regulatory authority, appraisal community and violator-promoter are reckoned. According to many activists, the reluctance of the MoEF&CC in translating the draft document in vernacular languages for people without any literacy in Hindi and English further favour the majority. While massive online protests, public feedbacks and petitions ensued, there were cases of websites blocked by filing Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA) to few environmental groups such as ‘Fridays For Future’ and others (Kunal 2020).

Nonetheless, the Ministry has appointed the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) to compile the comments received from the public. Post which the final draft will be scrutinised by the committee headed under SR Wate, former director of NEERI who was already given the mandate to re-engineering EIA 2006 and had chaired panels such as appraisal on post-factor clearance (Jackson and Gunasekar 2020). This poses a predicament, as the appointment of the above-mentioned individual might already have a biased viewpoint over the draft.

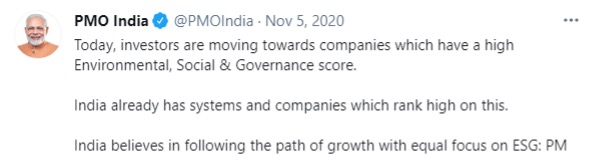

The global economy, particularly the developed countries are working towards building an entire ecosystem of environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing. They were developed while keeping societal impact and the conservation and preservation of nature in mind. Various civil groups and governments are becoming more and more acceptable in forfeiting their wealth which increases their domestic input costs in an order to choose merchandise producing lower greenhouse gas emissions. Many mutual funds and portfolios are available for ESG investing though there has not been a uniform standard set to determine these stocks make the cut (Borate 2020).

The adverse effect of polluting industries can be noted from the Environment Performance Index (EPI) 2020 by researchers in Yale and Columbia University which ranked India at 168th position out of 180 countries (“India EPI – Country Scorecard.” 2020).

EIA draft presents a contradiction on the government’s aim of emphasising ESG metric (Figure Below). We notice a diversion in the policymaking when the recent National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct (NGRBC) was laid down by the Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) in 2019. Based on which the subsequent consultation paper of the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR) from the top 100 to top 1000 listed market companies were released by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) (Consultation paper 2020).

EIA based on its principle was supposed to be a tool for the protection of natural resources and marginalised community who receive negative externalities from the polluting industries. The adverse effect of which can be noted from the Environment Performance Index (EPI) 2020 by researchers in Yale and Columbia University which ranked India at 168th position out of 180 countries (“India EPI – Country Scorecard.” 2020).

The author’s opinion over the larger framework is that environmental costs are being balanced with post-facto redressal. The emphasis put upon the private sector for green investing and other mandatory disclosures cannot be followed by diminishing the baseline surveys and the benchmark of EIA regulations. This can lead to more frequent outcomes of incidents such as Assam’s Baghjan oil spill and fire and the Vizag gas leak incident. Instead, the government should develop policies that restrain further ecological damages in the first place.

References:

Borate, Neil. “ESG Investments Are Fast Gaining Traction in India.” Mint, 11 Nov. 2020, www.livemint.com/money/personal-finance/esg-investments-are-fast-gaining-traction-in-india-11605111323843.html.

Consultation Paper on the Format for Business Responsibility and Sustainability Reporting. SEBI, 2020, www.sebi.gov.in/reports-and-statistics/reports/aug-2020/consultation-paper-on-the-format-for-business-responsibility-and-sustainability-reporting_47345.html.

Gupta, Debayan, et al. The Draft EIA Notification, 2020: Reduced Regulations and Increased Exemptions Part I & II, 31 July 2020, www.cprindia.org/research/reports/draft-eia-notification-2020-reduced-regulations-and-increased-exemptions-part-i-ii.

“India EPI – Country Scorecard.” Environment Performance Index (EPI), 2020, epi.yale.edu/epi-results/2020/country/ind.

Jackson, Jacqueline, and Karthik Gunasekar. “Decoding the Current Status of Draft EIA 2020.” The News Minute, 23 Sept. 2020, www.thenewsminute.com/article/decoding-current-status-draft-eia-2020-133728.

Kunal, Kumar. UAPA Charge in Notice to Environmental Group Fridays for Future Due to ‘Clerical Error’: Delhi Police. India Today, 23 July 2020, www.indiatoday.in/india/story/uapa-charge-in-notice-to-environmental-group-fridays-for-future-due-to-clerical-error-delhi-police-1703716-2020-07-23.

Vencatesan, Anjana. “[Commentary] The Two Faces of Environmental Regulation.” Mongabay, 21 Dec. 2020, india.mongabay.com/2020/12/commentary-the-two-faces-of-environmental-regulation/.