TPF Occasional Paper

TPF Occasional Paper

February 2021

The Current Situation

As Eastern Ladakh grapples with a severe winter in the aftermath of a violent and tension-filled 2020, much analysis concerning happenings on the India-Tibet border during the previous year has become available internationally and within India. Despite variance in individual perspectives and prognoses, the one issue starkly highlighted is that 2020 marks a turning point in the India-China relationship, which, shorn of diplomatese, has taken a clear adversarial turn.

Enough debate has taken place over the rationale and timing behind the Chinese action. It suffices to say that given the expansionist mindset of the Xi regime and its aspiration for primacy in Asia and across the world, it was a matter of time before China again employed leverages against India. In 2020 it was calibrated military pressure in an area largely uncontested after 1962, combined with other elements of hard power – heightened activity amongst India’s neighbours and in the Indian Ocean plus visibly enhanced collusivity with Pakistan This, despite platitudes to the contrary aired by certain China watchers inside India, who continued to articulate that existing confidence-building mechanisms (CBMs) would ensure peace on the border and good relations overall. Multiple incidents on the border over the last few years culminating in the loss of 20 Indian lives at Galwan have dispelled such notions.

Currently, in terms of militarization, the LAC in Eastern Ladakh can vie with the Line of Control (LOC) on the Western border.

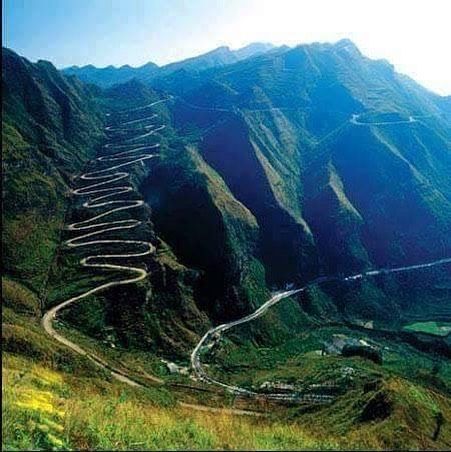

As an immediate consequence, the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in the arena of conflict in East Ladakh is seeing the heaviest concentration of troops in history, supplemented by fighter jets, utility and attack helicopters, the latest artillery acquisitions, armoured formations, road building teams and an inventory of drones, backed by matching logistics. Currently, in terms of militarization, the LAC in Eastern Ladakh can vie with the Line of Control (LOC) on the Western border.

Within the country, the perception of China as the principal foe has crystallised. At no other time since 1962 has China come in for such intense scrutiny. Indian public discourse is focused on China, towards interpreting its policies and implications for India and the world – all against the backdrop of international geopolitics churned further by the Covid pandemic.

China and the World in 2021

In 2017, President Xi Jinping had given a foretaste of things to come when spelling out his vision during the 19th Party Congress – that China has entered a “new era” where it should take the “centre stage in the world’[1]. In an insightful essay, Jake Sullivan (now National Security Adviser in the Biden administration) and Hal Brands have observed that ‘China has two distinct paths towards achieving this aim’ [2]. The first ‘focuses on building regional primacy as a springboard to global power’ while the second ‘focuses less on building a position of unassailable strength in the Western Pacific than on outflanking the U.S. alliance system and force presence in that region by developing China’s economic, diplomatic, and political influence on a global scale’. In the same piece, the authors sombrely conclude that the US ‘could still lose the competition with China even if it manages to preserve a strong military position in the Western Pacific….softer tools of competition—from providing alternative sources of 5G technology and infrastructure investment to showing competent leadership in tackling global problems—will be just as important as harder tools in dealing with the Chinese challenge…’ [3] These observations are prescient.

China and the Pandemic. A look at China’s conduct in this context and those of other nations over the last 12 months is instructive. The first aspect is its reaction to worldwide opprobrium for initially mishandling the Corona crisis – reprehensible wolf warrior diplomacy, crude attempts to divert the narrative about the origin of the Virus, unsuccessful mask diplomacy[4] and successfully delaying a WHO sponsored independent investigation into the matter for a full year without any guarantee of transparency. Secondly, it has exploited the covid crisis to strengthen its hold on the South China Sea commencing from March 2020 itself. Some examples are the renaming of 80 islands and geographical features in the Paracel and Spratly islands, commissioning research stations on Fiery Cross Reef and continued encroachment on fishing rights of Indonesia and Vietnam[5], in addition to a host of aggressive actions too numerous to mention, including ramming of vessels. Retaliatory actions from the US have continued, with the Trump administration in its final days sanctioning Chinese firms, officials, and even families for violation of international standards regarding freedom of navigation in January 2021[6]. The outgoing administration delivered the last blow on 19 January, by announcing that the US has determined that China has committed “genocide and crimes against humanity” in its repression of Uighur Muslims in its Xinjiang region[7]. As regards Taiwan, the Australian Strategic Policy Institute had recently forecast that China Taiwan relations will be heading for a crisis in a few weeks’ time,[8] (as borne out by serious muscle-flexing currently underway). If so, it would put the American system of alliances in the region since 1945 squarely to the test.

Pushback in the Indo Pacific. With China constantly pushing the envelope in its adjoining seas, the Quadrilateral Dialogue, whose existence over the last decade was marked only by a meeting of mid-level officials in Manila in November 2017, has acquired impetus. Initially dismissed as ‘sea foam’ by China, the individual interpretations of roles by each constituent have moved towards congruence, with Australia openly voicing disenchantment with China. Though an alliance is not on the cards, it can be concluded that increased interoperability between militaries of India, Australia, Japan and the US is both as an outcome and driver of this Dialogue, deriving from respective Indo Pacific strategies of member nations. Further expansion of its membership and tie-ups with other regional groupings is the practical route towards an egalitarian, long-lasting and open partnership for providing stability in this contested region. Japan’s expression of interest in joining the Five Eyes intelligence-sharing network of the US, UK, Canada, Australia and New Zealand[9], is a step in this direction. European nations like Germany, the Netherlands and France have recently declared their Indo Pacific strategies. France has provided the clearest articulation, with the French Ambassador in Delhi spelling out the prevailing sentiment in Europe about China, as ‘ a partner, a competitor and a systemic rival’[10], while further stating that “when China breaks rules, we have to be very robust and very clear”[11] . A blunt message befitting an Indo Pacific power, reflecting the sentiments of many who are yet to take a position.

BRI will see major reprioritisation – though its flagship program, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is unlikely to suffer despite disagreements on certain issues between the two countries.

Slowing of a Behemoth. China’s other driver the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), has considerably slowed in 2020. Lee YingHui, a researcher with Nanyang Technological Institute Singapore wrote last September ‘..in June this year, the Chinese Foreign Ministry announced that about 20 per cent of the projects under its ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) had been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. At the same press briefing, Wang Xiaolong, director-general at the Foreign Ministry’s International Economic Affairs Department, also revealed that a survey by the ministry estimated that some 30 to 40 per cent of projects had been somewhat affected, while approximately 40 per cent of projects were deemed to have seen little adverse impact[12]. Given the parlous condition of economies of client states post Covid-19 with many including Pakistan requesting a renegotiation of loans[13], BRI will see major reprioritisation – though its flagship program, the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) is unlikely to suffer despite disagreements on certain issues between the two countries.

Resilient Economy. China’s economy has rebounded fastest in the world, growing at 6.5 % in the final three months of 2020[14]. Despite the rate of annual growth being lowest in 40 years[15], its prominence in global supply chains has ensured some successes, such as the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment with the EU in December 2020. The deal, which awaits ratification by the European Parliament is more a diplomatic than an economic win for China, being perceived as detrimental to President Biden’s efforts to rejuvenate the Trans-Atlantic Alliance. China has notched up another win with the signing of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), where it along with 14 Asian countries from ASEAN and others (including Quad members like Australia and Japan) have agreed on an ‘ integrated market’. Given India’s position on the RCEP, how this agreement pans out and implications for its members will be watched with interest.

America in the New Year. The Biden Administration’s initial actions reaffirm the bipartisan consensus achieved last year on dealing with China. Comments of Secretary of State Anthony Blinken that ‘China presents the “most significant challenge” to the US while India has been a “bipartisan success story” and the new US government may further deepen ties with New Delhi,’[16] were indicative, as were those of Gen Lloyd Austin the Secretary of Defence during his confirmatory hearing[17]. President Biden’s first foreign policy speech on 04 February that ‘America is Back’ have provided further clarity. Earlier, Blinken and Austin had dialled Indian counterparts NSA Doval and Defence minister Rajnath Singh to discuss terrorism, maritime security, cybersecurity and peace and stability in the Indo Pacific.[18]Economically, American interest in joining or providing alternatives to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP, with an 11 nation membership, born out of President Trump’s withdrawal from its previous format, the TPP), will be another determinant in matters of trade with China. Harsh national security challenges will test the new administration’s resolve, as has already happened in the South China Sea over Taiwan where at the time of writing, the USS Theodore Roosevelt is conducting Freedom of Navigation operations[19]. Similar tests will occur over North Korea and Tibet, where the Senate’s passage of the Tibet Policy and Support Act 2020 mandates that decisions regarding the Dalai Lama’s succession be taken exclusively by the Tibetan people and the incumbent. Overall, a sense of how the world including the US will deal with China in 2021 is well captured by Commodore Lalit Kapur of the Delhi Policy Group when he states that ‘ …China has become too unreliable to trust, too powerful and aggressive to ignore and too prosperous, influential and connected to easily decouple from………[20] Going back to the views essayed by Sullivan and Brands, it appears that China is following both paths to achieve its objective, ie Great Power status.

India and China

The Early Years India’s attempt, soon after independence to develop a relationship with China, its ‘civilisational neighbour’ was overshadowed by the new threat to its security as the PLA invaded Tibet in 1950 – effectively removing the buffer between the two large neighbours. Dalai Lama’s flight to India in March 1959, the border clash at Hot Springs in Ladakh six months later and the subsequent 1962 war shattered our illusions of fraternity. Documents published recently pertaining to the period from 1947 to the War and beyond[21], reveal differences in perception within the Indian government in the run-up to 1962 despite the availability of sufficient facts. This combined with Chinese duplicity and disinformation, Indian domestic and international compulsions resulted in disjointed decision making, leading to the disastrous decision to implement the ‘Forward Policy’ with an unprepared military. A brief period of security cooperation with the US ensued including the signing of a Mutual Defence Agreement.[22] However, the US-China rapprochement of the early 70s and India’s professed non-alignment ensured its diminished status in the great power calculus.

Reaching Out to China. India’s outreach to China commenced with Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi’s visit to Beijing in 1988 in the aftermath of the Chinese intrusion at Somdorung Chu in 1986 in Arunachal Pradesh, resulting in a full-fledged standoff which lasted till mid-1987. The consequent push towards normalisation of relations resulted in the September 1993 Agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquillity along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas, the November 1996 Agreement on Confidence Building Measures in the Military Field along the Line of Actual Control in the India-China Border Areas, followed thereafter by the Declaration on Principles for Relations and Comprehensive Cooperation between India and China, of June 2003 and finally the Agreement between the Government of the Republic of India and the Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Political Parameters and Guiding Principles for the Settlement of the India-China Boundary Question of April 2005, signed during the visit of Chinese premier Wen Jiabao, which also saw the India China relationship elevated to a ‘Strategic and Cooperative Partnership for Peace and Prosperity’.

Despite partially successful attempts to broad base the engagement, territorial sovereignty continued to dominate the India China agenda, as can be observed by the number of agreements signed on border management – with minimal outcomes. It appears now that what can only be construed as diffidence in dealing with China on the border (and other issues) arose not because of misplaced optimism over such agreements, but for several other reasons. Some were structural weaknesses, such as lack of development of the border areas and poor logistics. Others arose because of want of a full-throated consensus on how strong a line to take with a visibly stronger neighbour – aggravated by growing economic disparity and the limitations imposed by self-professed non-alignment, especially so in the absence of a powerful ally like the Soviet Union, which had disintegrated by 1991. Also, American support could not be taken for granted, as was the case in the 60s. Overall, the approach was one of caution. This, coupled with lack of long term border management specialists induced wishful myopia on the matter, which was dispelled periodically by border skirmishes or other impasses, before returning to ‘business as usual’.

The extent of Engagement Today. To objectively analyse the relationship, it is important to comprehend the extent of the India China engagement on matters other than security. In the context of trade and industry, a perusal of the website of the Indian embassy in Beijing provides some answers. There is a list of 24 agreements/ MoUs /protocols between the two countries on Science and Technology alone, covering fields as diverse as aeronautics, space technology, health and medicine, meteorology, agricultural sciences, renewable energy, ocean development, water resources, genomics, geology, and others. The Embassy brings out India’s concerns regarding trade including impediments to market access, noting that trade imbalances have been steadily rising, to reach $58.4 billion in 2018, reducing marginally to $56.95 in 2019, a first since 2005. The poor penetration of Indian banks in China, India’s second-largest shareholding (8%) in the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), and being the largest borrower from the New Investment Bank or NIB, a BRICS bank of which all members have equal shareholding provide an understanding of linkages between the countries in the banking sector[23]. Other areas of cooperation are in petroleum and railways.

Economic Fallout Post April 2020. After the Galwan incident, India has taken strong measures on the economic front against China, from banning over 250 software applications to a partial ban on various categories of white goods,and the imposition of anti-dumping duties on many others. The Consolidated FDI Policy of the Department for Promotion of Industry and Internal Trade dated 15 October 2020, mandates Government scrutiny of every Chinese investment proposal before approval. However, the paradox in the India China relationship is well illustrated by trade figures for the first half of the Financial Year 20-21, where China surpassed the USA to become India’s largest trading partner. India reduced imports from China but exports to China grew by a robust 26.2 per cent at $10.16 billion[24]. Also, conditionalities for borrowing from the AIIB and NIB have resulted in India having to permit Chinese firms to bid for works connected with projects funded by these institutions. Consequently in January this year, the contract for construction of a 5.6 km long underground stretch of the Rapid Rail Transit System in the National Capital Region has been awarded to a Chinese company, Shanghai Tunnel Engineering Company Limited.[25] As noted earlier, decoupling is not easy. Incentives for companies to relocate to India have been announced, with some investment flowing in from Google and Facebook, and plans for Samsung to relocate a factory to NOIDA[26]. Finally, India’s exclusion from the RCEP will also have to be factored in when negotiating a long term trade policy with China.

However, the paradox in the India China relationship is well illustrated by trade figures for the first half of the Financial Year 20-21, where China surpassed the USA to become India’s largest trading partner.

Soft Power and Academia. Indian soft power in China remains subservient to harsh security concerns despite oft-quoted historical antecedents. Some elements like Indian cinema continue to be extremely popular. Student exchange programs have taken shape, especially under the aegis of Confucius Institutes which have secured a toehold in some Indian campuses. Following the trend worldwide, their programs are also under scrutiny[27]. The few Indian students in China (less than 25000)[28] have been hit hard by the coronavirus. Overall, given the current state of engagement, employing soft power as an effective tool has limited potential. Exchange of scholars from policy and security think tanks has been a good way of imbibing a sense of the other, resulting in greater awareness. While the trust deficit and reasons for the same have always been highlighted by the Indian side, it has been the general experience that China has been less forthcoming in its responses.

Building Blocks for a China Policy

In the middle term, unless there is a concerted and verifiable effort by China, trade with that country will be overshadowed by security issues (the huge trade imbalance also becoming one of these !). The Indian economy has commenced its post-Covid recovery in the new year. The budget for FY 21-22, trade policies of others like the EU and the US, will impact economic policy, as will national security concerns.

Immediate security priorities vis a vis China are a mix of the geopolitical and purely military. These can broadly be outlined – safeguarding Indian interests in the Indian Ocean region and the littorals, holding the line in the high Himalayas and ensuring sanctity over Indian skies. The first being both a geopolitical and security matter would leverage all elements of statecraft including the military. The balance two are a direct outcome of India’s military power. These, intertwined with India’s multilateral approach towards cooperation in world fora would form the basis of dealing with China.

Countries in the neighbourhood other than Pakistan when in distress, look first towards India for relief – natural calamities, food shortages[29], and now the corona vaccine, where Indian generosity remains unsurpassed worldwide. India does not indulge in cheque book diplomacy, nor entice weaker neighbours into debt traps.

Managing the Neighbourhood. In South Asia, India is primus inter pares due to size, geographical location, resources, capability and potential. Its soft power, economic reach ( while not comparable to China’s) and associated linkages with other countries are huge, at times even considered overwhelming. Countries in the neighbourhood other than Pakistan when in distress, look first towards India for relief – natural calamities, food shortages[29], and now the corona vaccine, where Indian generosity remains unsurpassed worldwide. India does not indulge in cheque book diplomacy, nor entice weaker neighbours into debt traps. Despite ethnic linkages and security concerns resulting sometimes in what is perceived by others as ‘interventionist politics’, India’s respect for its neighbours’ sovereignty is absolute. This is in contrast to China, whose recent interventions in Nepal have led to rallies in front of the Chinese embassy[30]. Its pressure on the NLD government in Myanmar over BRI projects had again not been viewed favourably in that country,[31] though the trajectory that the China-Myanmar relationship now follows remains to be seen, with China attempting to support Myanmar’s military in international fora after the coup[32]. Within South Asia, strengthening delivery mechanisms, sticking to timelines in infrastructure projects, improving connectivity and resolving the myriad issues between neighbours without attempting a zero-sum game with China is the way forward for India, which should play by its considerable strengths. Simultaneously, it must look at growing challenges such as management of Brahmaputra waters and climate change, and leverage these concerns with affected neighbours.

Strengthening Military Capability. A more direct challenge lies more in the military field, and in measures necessary to overcome these. The justifiable rise in military expenditure during the current year would continue or even accelerate. The armed forces are inching towards a mutually agreed road map before implementing large scale organisational reforms. Conceptual clarity on integrated warfighting across the spectrum in multiple domains (including the informational ) is a sine qua non, more so when cyberspace and space domains are concerned. This mandates breaking up silos between the military and other specialist government agencies for optimisation and seamless cooperation. Also, while classical notions of victory have mutated, swift savage border wars as witnessed in Nagorno Karabakh remain live possibilities for India, with open collusion now established between China and Pakistan. As always, the study of the inventory, military capability of the adversary and his likely pattern of operations will yield valuable lessons. The armed forces have to prepare multiple options, to deal with a range of threats from full scale two front wars down to the hybrid, including responses to terrorist acts while ensuring sovereignty across the seas. Network-centric warfare will take centre stage, with information operations being vital for overall success, possibly even defining what constitutes victory.

Progress has been achieved in these directions. As an example, the first Indian weaponised drone swarm made its debut on Army Day 2021, and visuals of a ‘wingman drone’ underdevelopment have been shown during the Aero India 2021 at Bangalore. The military would be planning for operationalisation, induction, deployment, staffing and human resource aspects of this weapon platform with the nominated service. An estimate of the time required to resolve these issues as also for full-scale production of such systems and larger variants will dictate procurement decisions with respect to other land and air platforms providing similar standoff kinetic effects, and surveillance capability. A concurrent requirement to develop sufficient capability to counter such systems would doubtless be under scrutiny. In this regard, the outcome of the PLA merging its cyber and electronic warfare functions for multiple reasons merits attention.[33] While the Navy’s requirements to dominate the Indian Ocean are well appreciated, a consensus on its future role and the need (or otherwise) for a third aircraft carrier would decide the nature, type and numbers of future naval platforms – unmanned underwater vehicles, submarines, shore/ carrier-based aircraft and others. With decisions over the Tejas LCA induction finalised, induction of a state of the art platforms from the USA and France over the last few years and hope for the acquisition of new generation indigenous air defence systems[34] on the anvil, the IAF is set to gradually regain its edge. Overall, India’s military has to leverage the latest technology and develop the capability to fight in multiple domains, which its hard-earned experience in third-generation warfighting would complement. With restructuring planned concurrently, each decision will have to be fully informed and thought through – more so when mini faceoffs as has happened at Naku La in Sikkim this month continue to occur.

A Way Forward

Traditional Chinese thinking has simultaneously been dismissive and wary of India. In his seminal publication at the turn of the century, Stephen Cohen noted that ‘…from Beijing’s perspective India is a second rank but sometimes threatening state. It poses little threat to China by itself and it can be easily countered but Beijing must be wary of any dramatic increase in Indian power or an alliance between New Delhi and some hostile major state..’[35] As brought out in this paper, outlines of a grounded long term China policy based on previous experiences and new realities are visible. Rooted primarily in the security dimension followed thereafter by the economic, its success will be predicated on peace and tranquillity on the border, without entering into the trap of competition in either of the two domains. As pointed out by the Minister for External Affairs in his talk to the 13th All India Conference for China Studies this month [36] the India-China relationship has to be based on ‘mutuality… mutual respect, mutual sensitivity and mutual interests ..’. The EAM further noted that ‘expectations…. that life can carry on undisturbed despite the situation at the border, that is simply not realistic. There are discussions underway through various mechanisms on disengagement at the border areas. But if ties are to steady and progress, policies must take into account the learnings of the last three decades’[37].

Rooted primarily in the security dimension followed thereafter by the economic, its success will be predicated on peace and tranquillity on the border, without entering into the trap of competition in either of the two domains.

In the same talk, the EAM has laid down eight broad and eminently practical propositions as guidelines for future India-China relations. Most prominent of these is that peace and tranquillity on the border are a must if relations in other spheres are to develop. Also, the need to accept that a multipolar world can have a multipolar Asia as its subset. He stressed that reciprocity is the bedrock of a relationship, and sensitivities to each other’s aspirations, interests and priorities must be respected. Concurrently, management of divergences and differences between two civilizational states should be considered over the long term.

A China policy crafted on these principles would ensure that India’s concerns vis a vis its neighbour is addressed, within the larger National goal of all-round growth and development of India and its citizens in the 21st Century.

Notes:

[1] ‘Xi JinPing Heralds New Era of Chinese Power’ Dipanjan Ray Chaudhury, Economic Times 18 October 2017

[2] ‘China Has Two Paths To Global Domination’ Jake Sullivan, Hal Brands, Foreign Policy, 22 May 2020

[3] ibid

[4] ‘China’s Mask Diplomacy is Faltering.But the US isn’t Doing any better’ Charlie Campbell Time Magazine 03 April 2020

[5] ‘China’s Renewed Aggression in the South China Sea’ Gateway House Infographic 22 April 2020

[6] ‘US imposes new sanction on Beijing over South China Sea’ Mint 15 January 2021

[7] In parting shot, Trump administration declares China’s repression of Uighurs ‘genocide’ Humeyra Pamuk, Reuters 19 January 2021

[8] ‘Pacific Panic: China-Taiwan relations to reach breaking point in ‘next few weeks’ skynews.com.au 18 January 2021

[9] ‘Japan wants de facto ‘Six Eyes’ intelligence status: defence chief’ Daishi Abe and Rieko Miki Nikkei Asia 14 August 2020

[10] ‘Emmanuel Bonne’s interview to the Times of India’ 10 January 2021 Website of the French Embassy in New Delhi

[11] ‘When China breaks rules, we have to be very robust and clear: French diplomat’ Dinakar Peri, The Hindu 08 January 2021

[12] ‘COVID-19: The Nail in the Coffin of China’s Belt and Road Initiative?’ Lee YingHui, The Diplomat 28 September 2020

[13] ibid

[14] ‘Covid-19: China’s economy picks up, bucking global trend’ BBC.com 18 January 2021

[15] ibid

[16] ‘New US govt may look to further deepen ties with India: Blinken’ Elizabeth Roche, The Mint 21 Jan 2021

[17] ‘What Biden’s Defence Secretary Said About Future Relations With India, Pakistan’ Lalit K Jha, The Wire 20 January 2021

[18] ‘US NSA speaks to Doval, Def Secretary dials Rajnath’ Krishn Kaushik and Shubhajit Roy Indian Express 27 January 2021

[19] ‘As China Taiwan tension rises, US warships sail into region’ The Indian Express 25 January 2021

[20] ‘India and Australia: Partners for Indo Pacific Security and Stability’ Lalit Kapur, Delhi Policy Group Policy Brief Vol. V, Issue 42 December 15, 2020

[21] ‘India China Relations 1947-2000 A Documentary Study’ (Vol 1 to 5) Avtar Singh Bhasin Geetika Publishers New Delhi 2018

[22] ‘The Tibet Factor in India China Relations’ Rajiv Sikri Journal of International Affairs , SPRING/SUMMER 2011, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp 60

[23] Website of the Embassy of India at Beijing www.eoibeijing.gov.in

[24] ‘What an irony! Mainland China beats US to be India’s biggest trade partner in H1FY21’ Sumanth Banerji Business Today 04 December 2020

[25] ‘Chinese company bags vital contract for first rapid rail project’ Sandeep Dikshit The Tribune 03 January 2021

[26] ‘Samsung to invest Rs 4,825 cr to shift China mobile display factory to India’ Danish Khan Economic Times 11 December 2020

[27] ‘The Hindu Explains | What are Confucius Institutes, and why are they under the scanner in India?’

Ananth Krishnan The Hindu August 09 2020

[28] ‘23,000 Indian students stare at long wait to return to Chinese campuses’ Sutirtho Patranobis Hindustan Times 08 September 2020

[29] ‘Offering non-commercial, humanitarian food assistance to its neighbours: India at WTO’ Press Trust of India 19 December 2020

[30] ‘Torch rally held in Kathmandu to protest against Chinese interference’ ANI News 30 December 2020

[31] ‘Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visits Myanmar with aim to speed up BRI projects’ Dipanjan Roy Chaudhury Economic Times 09 January 2021

[32] ‘China blocks UNSC condemnation of Myanmar coup’ India Today Web Desk 03 February 2021

[33] ‘Electronic and Cyber Warfare: A Comparative Analysis of the PLA and the Indian Army’ Kartik Bommankanti ORF Occasional Paper July 2019

[34] ‘India successfully test fires new generation Akash NG missile’ Ch Sushil Rao Times of India 25 January 2021

[35] ‘ India Emerging Power’ Stephen Philip Cohen Brookings Institution Press 2001 pp 259

[36] Keynote Address by External Affairs Minister at the 13th All India Conference of China Studies January 28, 2021

[37] ibid