Milan Kundera, that remarkable novelist, essayist, poet, philosopher and political critic, has died at the age of 94. It feels too soon, perhaps because in everything he wrote, he opened up new ways of thinking, writing and reading. In his literary presence, the world seemed tuned to a higher frequency.

Kundera was born with immaculate timing, on April 1 (1929): April Fool’s Day. From the start, he was exposed to, and immersed in, the absurdity of human culture. He grew up in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, then lived under Stalinist rule, where he was an active member of the Communist Party.

I have been reading him, quoting him and teaching from his writings for decades, after bumping into his work in 1988. I was living then on an isolated sheep station in the Western Australian outback, a world of bleak beauty.

Someone visiting the property pressed on me a copy of The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, and I was immediately and utterly captivated. This, Kundera’s third novel, affirmed my own anxiety of the absence of a stable truth, and of my incapacity to resist the longing to belong, even to the most damaged society.

In one section of the novel, a group of the Communist faithful, dancing together in a circle, rise into the air and soar over the city. They laugh the laughter of angels while below them, the executioners are killing political prisoners. Says the narrator of this section, who necessarily cannot be part of that group:

I realized with anguish in my heart that they were flying like birds and I was falling like a stone, that they had wings and I would never have any.

Interrogating totalitarianism, with humour

Kundera knew about oppression and inhumanity. His first collection of (not very good) poetry, Man, A Wide Garden (1953) – published when he was only 24 – was decidedly Soviet in tone and content.

But when he wrote his first novel, The Joke in 1967, then wrote Life is Elsewhere in 1969 (published in 1973), both of them shot through with political satire, and he was expelled from the Communist Party and subsequently fled into exile.

In what is perhaps his best-known novel, The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1984) – adapted in 1988 as a movie starring Daniel Day-Lewis and Juliette Binoche – he continues his interrogation of totalitarian politics, exploring the Prague Spring and the brutality of Soviet control of Czechoslavakia.

This theme sounds deeply earnest. But in each novel, Kundera offers some humour – often bitter, but capable of leavening the otherwise bleak, and densely reported, content.

In Unbearable Lightness, for example, the narrator discusses Nietszche’s doctrine of eternal recurrence – the possibility we live the same life over and over. But he also develops an erotic narrative that seems to suggest lighthearted sex can allow us to live fully in the moment. We can exchange the weight of eternal recurrence for the lightness of being alive, here and now.

Weight and lightness, laughter and forgetting, repetition and change, politics and sex: his first four novels incorporate such dualities. Perhaps this capacity to hold contradictory thoughts can be explained by something he said to Philip Roth:

Totalitarianism is not only hell, but also the dream of paradise – the age old drama of a world where everybody would live in harmony.

Author in exile

His dream of paradise was not realised, of course. In 1975, he fled his home for exile in France, and continued writing works of fiction that mostly followed the signature structure he first developed in The Joke: multi-part, multi-voiced novels, where the narrator interpolates critique, commentary and philosophical statements in the text.

This makes for a restless story, one that shifts to and fro across locations, times and contexts. Characters flicker in and out. The logic of beginning, middle and end is barely acknowledged. And the sorts of issues that appear so often in fiction – a quest for the self, the telling of a tale, the achievement of resolution – are set aside.

The focus of Kundera’s novels is their wrestle with questions of knowledge, the complexity of being and a constant uncertainty. This can be an unsettling style: a disruption, rather than a simple pleasure or an aesthetic experience. For a 21st-century woman, too, his tone and style in the writing of sex scenes – and the representation of women more generally – can present as outdated masculinity.

I vacillate between feeling offence at what feels like misogyny, and reading it as a searing critique of misogyny. And I’m not alone in this.

‘Things are not as simple as you think’

Where I uncomplicatedly follow Kundera’s lead is not in his novels, but in his essays. Here, his deep understanding of the background to what we now know as the novel, or the long traditions and changes that characterise artistic practice, genuinely illuminate the field.

In The Art of the Novel (1986), he outlines a history of how novelists unpacked various dimensions of existence. He starts with Miguel de Cervantes and moves through the lists of generative fiction writers to fellow Czechs Franz Kafka and Jaroslav Hasek – who, he claims, show that a strength of fiction is that it tolerates uncertainty, in a way politics and religion cannot. For Kundera, what fiction does so well is say to the reader: “Things are not as simple as you think.”

For Kundera, the novel is a technological object that allows new ways of seeing, and of making meaning. And this seeing and meaning is embedded in its context. For example, in The Curtain: An Essay in Seven Parts (2006), he points out what fiction can do that earlier forms could not.

Homer never wondered whether, after all their many hand-to-hand battles, Achilles or Ajax still had all their teeth. But for Don Quixote and Sancho teeth are a perpetual concern – hurting teeth, missing teeth.

Writers like Cervantes (author of Don Quixote), Henry Fielding (Tom Jones) and Laurence Sterne (The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman) introduce the small things of everyday life, and illuminate the meaning and import they have on us, Kundera points out.

But, he hastens to observe, contemporary writers cannot and should not write as those giants did: rather, writing is a matter of continuity (in terms of form, voice and style in a particular period) and discontinuity (finding something new).

In these essays, too, he offers a workshop in how to write. How to manage voice, perspective, temporality. How to have fun with language and form – and let the imagination run wild. And how to deal with thought and concept, materiality and politics.

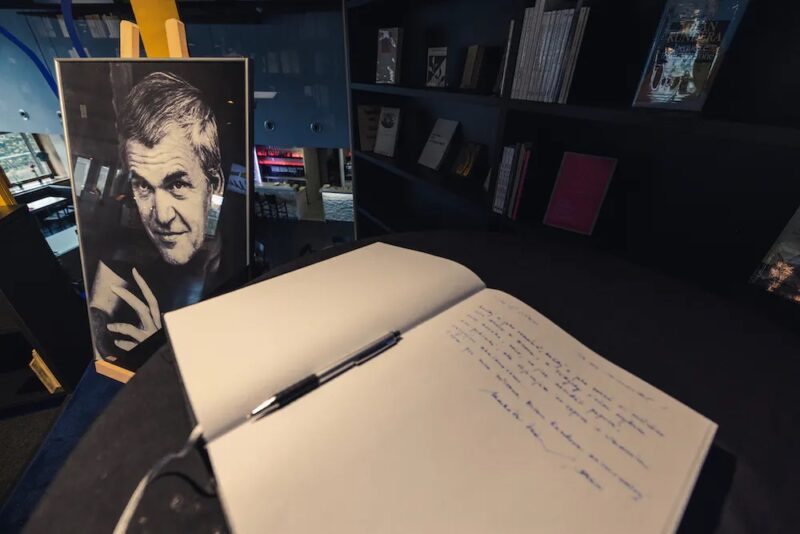

A condolence book and portrait of late writer Milan Kundera at the Milan Kundera Library in Brno Czech Republic T. Tomas Skoda/EPA

A condolence book and portrait of late writer Milan Kundera at the Milan Kundera Library in Brno Czech Republic T. Tomas Skoda/EPA

Teller of inconvenient truths

A writer of such gravitas and such technical brilliance should, one might imagine, have won the Nobel Prize in Literature at some point in his long life. He won other prizes, after all, among them the Jerusalem Prize in 1985 and the Herder Prize in 2000.

Perhaps it was his writing style that meant the Nobel committee saw him nominated on a number of occasions, but never awarded him the prize.

After the last novel he wrote in Czech – Immortality (1991), which teases out questions of sexual and personal relationships – he wrote four more novels, which garnered less attention, less critical reception. So, in Slowness (1995), Identity: A Novel (1999), Ignorance (2000) and finally The Festival of Insignificance (2014), you can see his star begin to fade.

This is not because they are less “good” books. Robin Ashenden suggests he “had become a teller of truths inconvenient to the modern age”, and maybe there is something in that.

He is terribly direct, very hard-hitting. And he refuses the consolations of sentimentality or morality, in favour of what he describes as the morality of knowledge: the imperative to see and say what previous writers did not/could not see, or say. And to build fresh understandings of the world.

This article was first published in The Conversation and is republished under Creative Commons license.