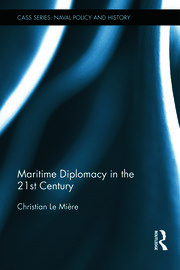

- Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (April 28, 2014)

- Author: Christian Le Mière – is a senior fellow for naval forces and maritime security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London.

- Language : English

- Hardcover : 160 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0415828007

- ISBN-13 : 978-0415828000

Maritime diplomacy means using maritime capabilities, strategies, and policies to achieve diplomatic objectives and foster international relations. It encompasses various activities maritime nations conduct to promote their interests, maintain security, and manage disputes in maritime domains. Maritime diplomacy has evolved significantly over time, driven by changes in geopolitical dynamics, technological advancements, economic interests, and environmental concerns. Maritime diplomacy adapts to emerging issues, such as cybersecurity and environmental concerns, while balancing economic, security, and diplomatic interests. Christian’s book redefined the concept of maritime diplomacy, presenting it as a multifaceted approach to achieving diplomatic objectives and fostering international relations. In his interpretation, maritime diplomacy encompasses maritime nations’ activities to promote their interests, ensure security, and manage disputes within maritime domains.

As a senior fellow for naval forces and maritime security at the International Institute for Strategic Studies, London, Christian Le Mière brings extensive expertise and insight to the field of maritime security.

“Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century,”[i] authored by Christian Le Mière, stands as a seminal work redefining the concept of maritime diplomacy in the contemporary era. Published in 2014, this book comprehensively explores maritime diplomacy’s significance, highlighting its relevance and utility amidst today’s complex geopolitical landscape. Le Mière’s analysis challenges conventional perceptions of maritime diplomacy, particularly debunking the notion of “gunboat diplomacy” as an outdated relic of the past. Instead, the book argues that coercive tactics persist in modern maritime affairs, profoundly shaping international relations.

Le Mière’s emphasis on the distinction between “naval” and “maritime” diplomacy underscores a critical aspect of contemporary maritime affairs. Traditionally, the term “naval diplomacy” has been used to describe diplomatic activities conducted exclusively by naval forces. However, Le Mière expands this concept to include a broader range of actors and activities, recognizing the involvement of non-military agencies such as maritime constabulary forces and paramilitary agencies in maritime diplomacy.

By incorporating these non-military entities into the framework of maritime diplomacy, Le Mière acknowledges the diverse spectrum of actors operating in maritime domains. Maritime constabulary forces, for example, are tasked with enforcing maritime laws and regulations, combating piracy, and conducting search and rescue operations. Paramilitary agencies, on the other hand, may be involved in maritime security operations or territorial defence activities.

The involvement of these non-traditional actors highlights the complex interplay between various stakeholders in maritime diplomacy. Unlike traditional naval forces, maritime constabulary forces and paramilitary agencies often collaborate with civilian authorities, international organizations, and other non-state actors. Their participation in diplomatic endeavours at sea reflects the multifaceted nature of maritime diplomacy, which extends beyond military engagements to encompass a wide range of cooperative, persuasive, and coercive activities.

The Book offers a rich exploration of the multifaceted nature of maritime diplomacy, drawing upon contemporary examples to illustrate its diverse spectrum of activities. One example highlighted in the book is Iran’s naval exercises, particularly the Velayat 90 exercises conducted in December 2011 and January 2012. These exercises showcased Iran’s naval capabilities, including anti-ship missiles and submarines, and were explicitly intended to signal Iran’s ability to exert control over the strategically vital Strait of Hormuz. Le Mière uses this example to underscore the continued relevance of coercive tactics in contemporary maritime affairs, emphasizing how such displays of naval power can have significant implications for global politics.

Additionally, Le Mière examines US deployments in East Asia as another pertinent example of maritime diplomacy in action. Specifically, he discusses the participation of the USS Abraham Lincoln in naval exercises in the East Sea (Sea of Japan) and the Yellow Sea in response to provocations from North Korea. These deployments, accompanied by allied vessels from countries like Britain and France, signal Washington’s resolve and commitment to its regional allies while deterring further aggression from North Korea. Through these examples, Le Mière highlights the dynamic nature of maritime diplomacy, which encompasses a wide range of activities to achieve diplomatic objectives and maintain security in maritime domains.

The book explores the theoretical underpinnings of maritime diplomacy, drawing upon insights from legal theorists like Wolfgang G. Friedmann. Le Mière argues that maritime diplomacy serves as a tool for signalling intentions, deterring conflicts, and promoting state interests but cautions that its failure can lead to unintended escalation.

Chapters delve into the drivers and dynamics of maritime diplomacy, including its role as an indicator of global power shifts and a predictive tool for conflict prevention. Le Mière also explores the application of game theory to analyse maritime diplomatic incidents, providing insights into decision-making processes and strategies for managing potential escalations.

It offers a multifaceted perspective on the evolving dynamics of maritime affairs and diplomatic engagements, making it a valuable resource across various domains. For scholars and researchers, the book provides a comprehensive analysis of maritime diplomacy, tracing its historical roots, examining contemporary manifestations, and proposing new theoretical frameworks. By delving into case studies and empirical data, scholars can gain insights into the complexities of maritime interactions and contribute to advancing knowledge in this field. Conversely, policymakers can leverage the book’s insights to formulate more informed maritime strategies, navigate geopolitical challenges, and promote international cooperation. With a nuanced understanding of the spectrum of maritime diplomacy, policymakers can effectively utilize naval deployments, diplomatic initiatives, and conflict resolution mechanisms to safeguard national interests and foster regional stability. The book offers practical guidance and real-world examples for practitioners engaged in maritime security and diplomacy, helping them navigate complex maritime disputes, leverage maritime assets for diplomatic purposes, and manage tensions in maritime regions.

Moreover, students studying international relations, maritime security, or diplomacy can benefit from the book’s comprehensive coverage. It can be used as a textbook or reference material to deepen their understanding of maritime affairs and global politics. Ultimately, “Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century” is an indispensable resource, informing policy debates, guiding practical decision-making, inspiring further research, and educating future leaders in maritime diplomacy’s complex and dynamic realm.

References:

[i] Maritime Diplomacy in the 21st Century, n.d.

Feature Image Credit: indiafoundation.in

ALFREDO TORO HARDY is a Venezuelan retired diplomat, scholar and author. He has a PhD in International Relations from the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Affairs, two master’s degrees in international law and international economics from the University of Pennsylvania and the Central University of Venezuela, a post-graduate diploma in diplomatic studies by the Ecole Nationale D’Administration (ENA) and a Bachelor of Law degree by the Central University of Venezuela. Before resigning from the Venezuelan Foreign Service in protest of events taking place in his country, he was one of its most senior career diplomats. As such, he served as Ambassador to the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil, Singapore, Chile and Ireland.

ALFREDO TORO HARDY is a Venezuelan retired diplomat, scholar and author. He has a PhD in International Relations from the Geneva School of Diplomacy and International Affairs, two master’s degrees in international law and international economics from the University of Pennsylvania and the Central University of Venezuela, a post-graduate diploma in diplomatic studies by the Ecole Nationale D’Administration (ENA) and a Bachelor of Law degree by the Central University of Venezuela. Before resigning from the Venezuelan Foreign Service in protest of events taking place in his country, he was one of its most senior career diplomats. As such, he served as Ambassador to the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain, Brazil, Singapore, Chile and Ireland.