While there is euphoria in Phnom Penh over the new responsibility, Prime Minister Hun Sen inherits at least five challenges from the previous ASEAN Chairmanship under Brunei.

The gavel representing the ASEAN has arrived in Phnom Penh and it is a proud moment for the country to hold the position of Chairmanship of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) for the third time after joining the grouping in 1999. In his customary remarks, Prime Minister Hun Sen announced that his country is “committed to leading ASEAN by championing the 2022 theme of “ASEAN Act” – Addressing Challenges Together – to increase harmony, peace and prosperity across the whole region”. He also assured to “uphold the core spirit of ASEAN’s basic principles of “One Vision, One Identity and One Community,”

While there is euphoria in Phnom Penh over the new responsibility, Prime Minister Hun Sen inherits at least five challenges from the previous ASEAN Chairmanship under Brunei. First is the South China Sea. Prime Minister HunSen did not hesitate to refer to it as “an unwelcome guest which now turns up on ASEAN’s doorstep annually and without fail”. He even labelled it a “very hot rock” amid fears that his country could be “tossed” requiring sophisticated diplomacy wherein it is necessary to “catching it to avoid getting burned”

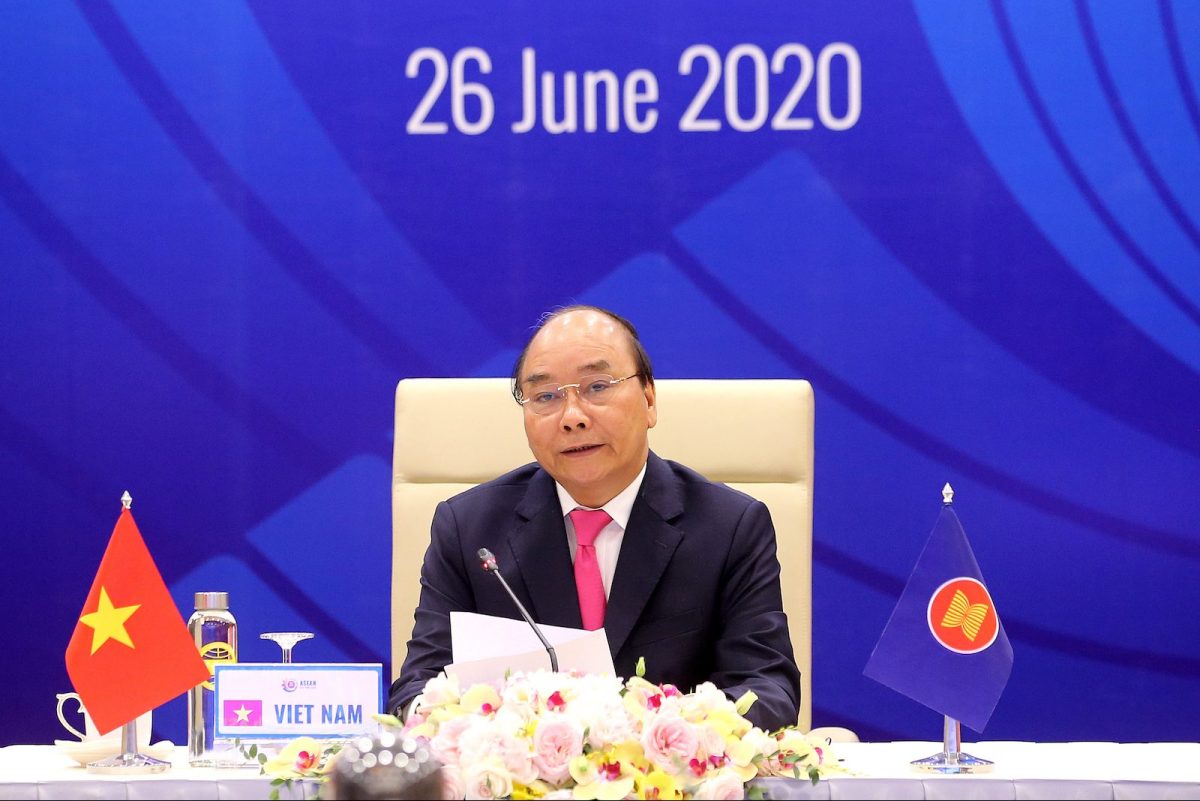

In this context, it is useful to recall the 26 October 2021 Chairman’s Statement of the 24th ASEAN-China Summit which emphasised the “importance of non-militarisation and self-restraint in the conduct of all activities by claimants and all other states, including those mentioned in the DOC that could further complicate the situation and escalate tensions in the South China Sea”. China continues to engage in exploration activities in the region much to the discomfort of the Philippines. Malaysia, Vietnam and Indonesia. Also, the Chinese coast guard vessels have engaged in coercion and their operations potentially undermine the ongoing negotiations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC).

The second is about ASEAN’s post-pandemic economic recovery. So far ASEAN Member States’ economic indicators are quite promising and marked by positive growth rates. Cambodia has an opportunity to prepare the region and the human resources for the impending disruption that will be marked by Industry 4.0 technologies. It requires regional digitalisation and impetus to fintech through innovation pivoting on resilience across sectors. This issue is also highlighted in the Chairman’s Statement of the 38th and 39th ASEAN Summits. The ASEAN Leaders’ Statement on Advancing Digital Transformation in ASEAN has also called for strengthening “regional digital integration and transformation to enhance the region’s competitiveness, and turn the current pandemic crisis into an opportunity through digital transformation.”

The third issue is about Myanmar. It may be recalled that Myanmar did not participate in the 38th and 39thASEAN Summits after the ASEAN decided to bar Myanmar’s military chief Min Aung Hlaing to join the meeting. This decision, by all accounts, was a “rare bold step by a regional grouping known for its non-interference and engagement”. Prime Minister Hun Sen is concerned about the possibility of a humanitarian crisis in the country and was quite candid to note that the “situation in Myanmar could escalate – and maybe even turn into a full-scale civil war – and so Cambodia must be well-prepared and ready to deal with any potential crisis there.”

The fourth priority for Cambodia as the Chairmanship of the ASEAN would be to take forward the objectives and principles of the ASEAN Outlook for Indo Pacific (AIOP) initiative. ASEAN’s engagement in the wider Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean regions would be in four key areas i.e. Maritime cooperation, connectivity, UN SDGs 2030, economic and other possible areas of cooperation. However, the grouping believes that the existing ASEAN-led mechanisms should drive the AIOP for which Cambodia would have to marshal all diplomatic skills at its disposal to convince the major players in the Indo-Pacific of the importance of the AOIP as also about ASEAN’s centrality.

Although AUKUS did not feature in Prime Minister Hun Sen’s remarks or the Chairman’s statement on the 38th and 39th ASEAN Summits, it looms large in the minds of the Member States

Fifth, Cambodia would have to develop a sophisticated response to the AUKUS which has added a new dimension to the existing security challenges emerging from the QUAD which is allegedly targeted against China. Although AUKUS did not feature in Prime Minister Hun Sen’s remarks or the Chairman’s statement on the 38th and 39th ASEAN Summits, it looms large in the minds of the Member States. Indonesian and Malaysian are concerned fearing that the development can result in an arms race and encourage the buildup of power projection capabilities; however, the Philippines has welcomed the AUKUS. The current situation is akin to the division among the ASEAN Member States over the presence of the Western military in the region. AUKUS has provoked China too and it can potentially intensify US-China military contestation in the western Pacific that further adds to insecurities among the Southeast Asian countries.

Finally, Cambodia’s Chairmanship of the ASEAN attracts numerous challenges but it remains to be seen how Phnom Penh steers the ASEAN in the coming months particularly when the US too has come down heavily with sanctions on Cambodia after it permitted a Chinese company to build military-naval infrastructure at the Ream Naval Base arguing that it threatens regional security.

Image Credit: cambodianess.com