America’s military-industrial complex (MIC) has grown enormously powerful and fully integrated into the Department of Defense of the US Government to further its global influence and control. Many American universities have become research centres for the MIC. Similarly, American companies have research programs in leading universities and educational institutions across the world, for example in few IITs in India. In the article below, Dr Sylvia J. Martin explores the role of University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs) in the U.S. military-industrial complex. UARCs are institutions embedded within universities, designed to conduct research for the Department of Defense (DoD) and other military agencies. The article highlights how UARCs blur the lines between academic research and military objectives, raising ethical questions about the use of university resources for war-related activities. These centres focus on key areas such as nano-technology, immersive simulations, and weapons systems. For example, the University of South California’s Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT) was created to develop immersive training simulations for soldiers, drawing from both science and entertainment, while universities like Johns Hopkins and MIT are involved in anti-submarine warfare and soldier mobility technologies. Sylvia Martin critically examines the consequences of these relationships, particularly their impact on academic freedom and the potential prioritization of military needs over civilian research. She flags the resistance faced by some universities, like the University of Hawai’i, where concerns about militarisation, environmental damage and indigenous rights sparked protests against their UARCs. As UARCs are funded substantially, it becomes a source of major influence on the university. Universities, traditionally seen as centres for open, unbiased inquiry may become aligned with national security objectives, further entrenching the MIC within academics.

This article was published earlier in Monthly Review.

– TPF Editorial Team

UARCs: The American Universities that Produce Warfighters

Dr Sylvia J Martin

The University of Southern California (USC) has been one of the most prominent campuses for student protests against Israel’s campaign in Gaza, with students demanding that their university “fully disclose and divest its finances and endowment from companies and institutions that profit from Israeli apartheid, genocide, and occupation in Palestine, including the US Military and weapons manufacturing.”

Students throughout the United States have called for their universities to disclose and divest from defense companies with ties to Israel in its onslaught on Gaza. While scholars and journalists have traced ties between academic institutions and U.S. defense companies, it is important to point out that relations between universities and the U.S. military are not always mediated by the corporate industrial sector.1 American universities and the U.S. military are also linked directly and organizationally, as seen with what the Department of Defense (DoD) calls “University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs).” UARCs are strategic programs that the DoD has established at fifteen different universities around the country to sponsor research and development in what the Pentagon terms “essential engineering and technology capabilities.”2Established in 1996 by the Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, UARCs function as nonprofit research organizations at designated universities aimed to ensure that those capabilities are available on demand to its military agencies. While there is a long history of scientific and engineering collaboration between universities and the U.S. government dating back to the Second World War, UARCs reveal the breadth and depth of today’s military-university complex, illustrating how militarized knowledge production emerges from within the academy and without corporate involvement. UARCs demonstrate one of the less visible yet vital ways in which these students’ institutions help perpetuate the cycle of U.S.-led wars and empire-building.

The University of Southern California (USC) has been one of the most prominent campuses for student protests against Israel’s campaign in Gaza, with students demanding that their university “fully disclose and divest its finances and endowment from companies and institutions that profit from Israeli apartheid, genocide, and occupation in Palestine, including the US Military and weapons manufacturing.”3 USC also happens to be home to one of the nation’s fifteen UARCs, the Institute of Creative Technology (ICT), which describes itself as a “trusted advisor to the DoD.”4 ICT is not mentioned in the students’ statement, yet the institute—and UARCs at other universities—are one of the many moving parts of the U.S. war machine that are nestled within higher education institutions, and a manifestation of the Pentagon’s “mission creep” that encompasses the arts as well as the sciences.5

Institute of Creative Technologies – military.usc.edu

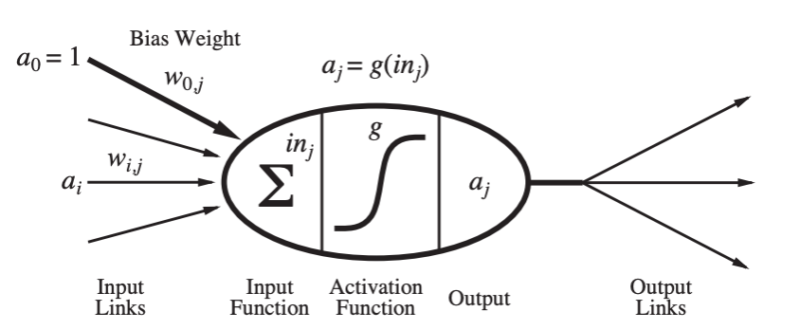

Significantly, ICT’s remit to develop dual-use technologies (which claim to provide society-wide “solutions”) entails nurturing what the Institute refers to as “warfighters” for the battlefields of the future, and, in doing so, to increase warfighters’ “lethality.6 Established by the DoD in 1999 to pursue advanced modelling and simulation and training, ICT’s basic and applied research produces prototypes, technologies, and know-how that have been deployed for the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marine Corps. From artificial intelligence-driven virtual humans deployed to teach military leadership skills to futuristic 3D spatial visualization and terrain capture to prepare these military agencies for their operational environments, ICT specializes in immersive training programs for “mission rehearsal,” as well as tools that contribute to the digital innovations of global warmaking.7 Technologies and programs developed at ICT were used by U.S. troops in the U.S.-led Global War on Terror. One such program is UrbanSim, a virtual training application initiated in 2006 designed to improve army commanders’ skills for conducting counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan, delivering fictional scenarios through a gaming experience.8 From all of the warfighter preparation that USC’s Institute researches, develops, prototypes, and deploys, ICT boasts of generating over two thousand academic peer-reviewed publications.

I encountered ICT’s work while conducting anthropological research on the relationship between the U.S. military and the media entertainment industry in Los Angeles.9 The Institute is located not on the university’s main University Park campus but by the coast, in Playa Vista, alongside offices for Google and Hulu. Although ICT is an approximately thirty-minute drive from USC’s main campus, this hub for U.S. warfighter lethality was enabled by an interdisciplinary collaboration with what was then called the School of Cinema-Television and the Annenberg School for Communications, and it remains entrenched within USC’s academic ecosystem, designated as a unit of its Viterbi School of Engineering, which is located on the main campus.10 Given the presence and power of UARCs at U.S. universities, we can reasonably ask: What is the difference between West Point Military Academy and USC, a supposedly civilian university? The answer, it seems, is not a difference in kind, but in degree. Indeed, universities with UARCs appear to be veritable military academies.

What Are UARCs?

UARCs are similar to federally funded research centres such as the Rand Corporation; however, UARCs are required to be situated within a university, which can be public or private.11 The existence of UARCs is not classified information, but their goals, projects, and implications may not be fully evident to the student bodies or university communities in which they are embedded, and there are differing levels of transparency among them about their funding. DoD UARCs “receive sole source funds, on average, exceeding $6 million annually,” and may receive other funding in addition to that from their primary military or federal sponsor, which may also differ among the fifteen UARCs.12 In 2021, funding from federal sources for UARCs ranged “from as much as $831 million for the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Lab to $5 million for the University of Alaska Geophysical Detection of Nuclear Proliferation.”13 Individual UARCs are generally created after the DoD’s Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering initiates a selection process for the proposed sponsor, and typically are reviewed by their primary sponsor every five years for renewed contracts.14 A few UARCs, such as Johns Hopkins University’s Applied Physics Lab and the University of Texas at Austin’s Applied Research Lab, originated during the Second World War for wartime purposes but were designated as UARCs in 1996, the year the DoD formalized that status.15

UARCs are supposed to provide their sponsoring agency and, ultimately, the DoD, access to what they deem “core competencies,” such as MIT’s development of nanotechnology systems for the “mobility of the soldier in the battlespace” and the development of anti-submarine warfare and ballistic and guided missile systems at Johns Hopkins University.16 Significantly, UARCs are mandated to maintain a close and enduring relationship with their military or federal sponsor, such as that of ICT with the U.S. Army. These close relationships are intended to facilitate the UARCs’ “in-depth knowledge of the agency’s research needs…access to sensitive information, and the ability to respond quickly to emerging research areas.”17 Such an intimate partnership for institutions of higher learning with these agencies means that the line between academic and military research is (further) blurred. With the interdisciplinarity of researchers and the integration of PhD students (and even undergraduate interns) into UARC operations such as USC’s ICT, the question of whether the needs of the DoD are prioritized over those of an ostensibly civilian institute of higher learning practically becomes moot: the entanglement is naturalized by a national security logic.

Table 1 UARCs: The American Universities that Produce Warfighters

| Primary Sponsor | University | UARC | Date of Designation (*original year established) |

| Army | University of Southern California | Institute of Creative Technologies | 1999 |

| Army | Georgia Institute of Technology | Georgia Tech Research Institute | 1996 (*1995) |

| Army | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies | 2002 |

| Army | University of California, Santa Barbara | Institute for Collaborative Biotechnologies | 2003 |

| Navy | Johns Hopkins University | Applied Physics Laboratory | 1996 (*1942) |

| Navy | Pennsylvania State University | Applied Research Laboratory | 1996 (*1945) |

| Navy | University of Texas at Austin | Applied Research Laboratories | 1996 (*1945) |

| Navy | University of Washington | Applied Physics Laboratory | 1996 (*1943) |

| Navy | University of Hawai’i | Applied Research Laboratory | 2004 |

| Missile Defense Agency | Utah State University | Space Dynamics Laboratory | 1996 |

| Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security | University of Maryland, College Park | Applied Research Laboratory for Intelligence and Security | 2017 (*2003) |

| Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering | Stevens Institute of Technology | Systems Engineering Research Center | 2008 |

| U.S. Strategic Command | University of Nebraska | National Strategic Research Institute | 2012 |

| Department of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Threat Reduction and Control) | University of Alaska Fairbanks | Geophysical Detection of Nuclear Proliferation | 2018 |

| Air Force | Howard University | Research Institute for Tactical Autonomy | 2023 |

Sources: Joan Fuller, “Strategic Outreach—University Affiliated Research Centers,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Research and Engineering), June 2021, 4; C. Todd Lopez, “Howard University Will Be Lead Institution for New Research Center,” U.S. Department of Defense News, January 23, 2023.

A Closer Look

The UARC at USC is unique from other UARCs in that, from its inception, the Institute explicitly targeted the artistic and humanities-driven resources of the university. ICT opened near the Los Angeles International Airport, in Marina del Rey, with a $45 million grant, tasked with developing a range of immersive technologies. According to the DoD, the core competencies that ICT offers include immersion, scenario generation, computer graphics, entertainment theory, and simulation technologies; these competencies were sought as the DoD decided that they needed to create more visually and narratively compelling and interactive learning environments for the gaming generation.18 USC was selected by the DoD not just because of the university’s work in science and engineering but also its close connections to the media entertainment industry, which USC fosters from its renowned School of Cinematic Arts (formerly the School of Cinema-Television), thereby providing the military access to a wide range of storytelling talents, from screenwriting to animation. ICT later moved to nearby Playa Vista, part of Silicon Beach, where the military presence also increased; by April 2016, the U.S. Army Research Lab West opened next door to ICT as another collaborative partner, further integrating the university into military work.19 This university-military partnership results in “prototypes that successfully transition into the hands of warfighters”; UARCs such as ICT are thus rendered a crucial link in what graduate student worker Isabel Kain from the Researchers Against War collective calls the “military supply chain.”20

universities abandon any pretence to neutrality once they are assigned UARCs, as opponents at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa) asserted when a U.S. Navy-sponsored UARC was designated for their campus in 2004. UH Mānoa faculty, students, and community members repeatedly expressed their concerns about the ethics of military research conducted on their campus, including the threat of removing “researchers’ rights to refuse Navy directives”

USC was touted as “neutral ground” from which the U.S. Army could help innovate military training by one of ICT’s founders in his account of the Institute’s origin story.21 Yet, universities abandon any pretence to neutrality once they are assigned UARCs, as opponents at the University of Hawai’i at Mānoa (UH Mānoa) asserted when a U.S. Navy-sponsored UARC was designated for their campus in 2004. UH Mānoa faculty, students, and community members repeatedly expressed their concerns about the ethics of military research conducted on their campus, including the threat of removing “researchers’ rights to refuse Navy directives.”22 The proposed UARC at UH Mānoa occurred within the context of university community resistance to U.S. imperialism and militarism, which have inflicted structural violence on Hawaiian people, land, and waters, from violent colonization to the 1967 military testing of lethal sarin gas in a forest reserve.23 Hawai’i serves as the base of the military’s U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, where “future wars are in development,” professor Kyle Kajihiro of UH Mānoa emphasizes.24

Writing in Mānoa Now about the proposed UARC in 2005, Leo Azumbuja opined that “it seems like ideological suicide to allow the Navy to settle on campus, especially the American Navy.”25 A key player in the Indo-Pacific Command, the U.S. Navy has long had a contentious relationship with Indigenous Hawaiians, most recently with the 2021 fuel leakage from the Navy’s Red Hill fuel facility, resulting in water contamination levels that the Hawai’i State Department of Health referred to as “a humanitarian and environmental disaster.”26 Court depositions have since revealed that the Navy knew about the fuel leakage into the community’s drinking water but waited over a week to inform the public, even as people became ill, making opposition to its proposed UARC unsurprising, if not requisite.27 The detonation of bombs and sonar testing that happens at the biennial international war games that the U.S. Navy has hosted in Hawai’i since 1971 have also damaged precious marine life and culturally sacred ecosystems, with the sonar tests causing whales to “swim hundreds of miles, rapidly change their depth (sometimes leading to bleeding from the eyes and ears), and even beach themselves to get away from the sounds of sonar.”28 Within this context, one of the proposed UARC’s core competencies was “understanding of [the] ocean environment.”29

In a flyer circulated by DMZ Hawai‘i, UH Mānoa organizers called for universities to serve society, and “not be used by the military to further their war aims or to perfect ways of killing or controlling people.”30 Recalling efforts in previous decades on U.S. campuses to thwart the encroachment of military research, protestors raised questions about the UARC’s accountability and transparency regarding weapons production within the UH community. UH Mānoa’s strategic plan during the time that the Navy’s UARC was proposed and executed (2002–2010) called for recognition of “our kuleana (responsibility) to honour the Indigenous people and promote social justice for Native Hawaiians” and “restoring and managing the Mānoa stream and ecosystem”—priorities that the actions of the U.S. Navy disregarded.31 The production of knowledge for naval weapons within the auspices of this public, land-grant institution disrupts any pretension to neutrality the university may purport.

while the UH administration claimed that the proposed UARC would not accept any classified research for the first three years, “the base contract assigns ‘secret’ level classification to the entire facility, making the release of any information subject to the Navy’s approval,” raising concerns about academic freedom, despite the fanfare over STEM and rankings

Further resistance to the UARC designation was expressed by the UH Mānoa community: from April 28 to May 4, 2005, the SaveUH/StopUARC Coalition staged a six-day campus sit-in protest, and later that year, the UH Mānoa Faculty Senate voted 31–18 in favour of asking the administration to reject the UARC designation.32 According to an official statement released by UH Mānoa on January 23, 2006, at a university community meeting with the UH Regents in 2006, testimony from opponents to the UARC outnumbered supporters, who, reflecting the neoliberal turn of universities, expressed hope that their competitiveness in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) would advance with a UARC designation, and benefit the university’s ranking.33 Yet in 2007, writing in DMZ Hawai‘i, Kajihiro clarified that while the UH administration claimed that the proposed UARC would not accept any classified research for the first three years, “the base contract assigns ‘secret’ level classification to the entire facility, making the release of any information subject to the Navy’s approval,” raising concerns about academic freedom, despite the fanfare over STEM and rankings.34 However, the campus resistance campaign was unsuccessful, and in September 2007, the UH Regents approved the Navy UARC designation. By 2008, the U.S. Navy-sponsored Applied Research Laboratory UARC at UH Mānoa opened.

“The Military Normal”

Yet with the U.S. creation of the national security state in 1947 and its pursuit of techno-nationalism since the Cold War, UARCs are direct pipelines to the intensification of U.S. empire

UH Mānoa’s rationale for resistance begs the question: how could this university—indeed, any university—impose this military force onto its community? Are civilian universities within the United States merely an illusion, a deflection from education in the service of empire? What anthropologist Catherine Lutz called in 2009 the ethos of “the military normal” in U.S. culture toward its counterinsurgency wars in Iraq and Afghanistan—the commonsensical, even prosaic perspective on the inevitability of endless U.S.-led wars disseminated by U.S. institutions, especially mainstream media—helps explain the attitude toward this particular formalized capture of the university by the DoD.35 Defense funding has for decades permeated universities, but UARCs perpetuate the military normal by allowing the Pentagon to insert itself through research centres and institutes in the (seemingly morally neutral) name of innovation, within part of a broader neoliberal framework of universities as “engines” and “hubs,” or “anchor” institutions that offer to “leverage” their various forms of capital toward regional development in ways that often escape sustained scrutiny or critique.36 The normalization is achieved in some cases given that UARCs such as ICT strive to serve civilian needs as well as military ones with dual-use technologies and tools. Yet with the U.S. creation of the national security state in 1947 and its pursuit of techno-nationalism since the Cold War, UARCs are direct pipelines to the intensification of U.S. empire. Some of the higher-profile virtual military instructional programs developed at ICT at USC, such as its Emergent Leader Immersive Training Environment (ELITE) system, which provides immersive role-playing to train army leaders for various situations in the field, are funnelled to explicitly military-only learning institutions such as the Army Warrant Officer School.37

The fifteenth and most recently created UARC, at Howard University in 2023—the first such designation for one of the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs)—boasts STEM inclusion

The military normal generates a sense of moral neutrality, even moral superiority. The logic of the military normal, the offer of STEM education and training, especially through providing undergraduate internships and graduate training, and of course funding, not only rationalizes the implementation of UARCs, but ennobles it. The fifteenth and most recently created UARC, at Howard University in 2023—the first such designation for one of the historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs)—boasts STEM inclusion.38 Partnering with the U.S. Air Force, Howard University’s UARC is receiving a five-year, $90 million contract to conduct AI research and develop tactical autonomy technology. Its Research Institute for Tactical Autonomy (RITA) leads a consortium of eight other HCBUs. As with the University of Hawai’i, STEM advantages are touted by the UARC, with RITA’s reach expanding in other ways: it plans to supplement STEM education for K–12 students to “ease their path to a career in the fields of artificial intelligence, cybersecurity, tactical autonomy, and machine learning,” noting that undergraduate and graduate students will also be able to pursue fully funded research opportunities at their UARC. With the corporatization of universities, neoliberal policies prioritize STEM for practical reasons, including the pursuit of university rankings and increases in both corporate and government funding. This fits well with increased linkages to the defence sector, which offers capital, jobs, technology, and gravitas. In a critique of Howard University’s central role for the DoD through its new UARC, Erica Caines at Black Agenda Reportinvokes the “legacies of Black resistance” at Howard University in a call to reduce “the state’s use of HBCUs.”39 In another response to Howard’s UARC, another editorial in Black Agenda Report draws upon activist Kwame Ture’s (Stokely Carmichael’s) autobiography for an illuminative discussion about his oppositional approach to the required military training and education at Howard University during his time there.40

With their respectability and resources, universities, through UARCs, provide ideological cover for U.S. war-making and imperialistic actions, offering up student labour at undergraduate and graduate levels in service of that cover. When nearly eight hundred U.S. military bases around the world are cited as evidence of U.S. empire and the DoD requires research facilities to be embedded within places of higher learning, it is reasonable to expect that university communities—ostensibly civilian institutions—ask questions about UARC goals and operations, and how they provide material support and institutional gravitas to these military and federal agencies.41 In the case of USC, ICT’s stated goal of enhancing warfighter lethality runs counter to current USC student efforts to strive for more equitable conditions on campus and within its larger community (for example, calls to end “land grabs,” and “targeted repression and harassment of Black, Brown and Palestinian students and their allies on and off campus”) as well as other reductions in institutional harms.42 The university’s “Minor in Resistance to Genocide”—a program pursued by USC’s discarded valedictorian Asna Tabassum—also serves as mere cover, a façade, alongside USC’s innovations for warfighter lethality.

the Hopkins Justice Collective at Johns Hopkins University recently proposed a demilitarization process to its university’s Public Interest Investment Advisory Committee that cited Johns Hopkins’s UARC, Applied Physics Lab, as being the “sole source” of DoD funding for the development and testing of AI-guided drone swarms used against Palestinians in 2021

Many students and members of U.S. society want to connect the dots, as evident from the nationwide protests and encampments, and a push from within the academy to examine the military supply chain is intensifying. In addition to Researchers Against War members calling out the militarized research that flourishes in U.S. universities, the Hopkins Justice Collective at Johns Hopkins University recently proposed a demilitarization process to its university’s Public Interest Investment Advisory Committee that cited Johns Hopkins’s UARC, Applied Physics Lab, as being the “sole source” of DoD funding for the development and testing of AI-guided drone swarms used against Palestinians in 2021.43 Meanwhile, at UH Mānoa, the struggle continues: in February 2024, the Associated Students’ Undergraduate Senate approved a resolution requesting that the university’s Board of Regents terminate UH’s UARC contract, noting that UH’s own president is the principal investigator for a $75 million High-Performance Computer Center for the U.S. Air Force Research Laboratory that was contracted by the university’s UARC, Applied Research Laboratory.44 Researchers Against War organizing, the Hopkins Justice Collective’s proposal, the undaunted UH Mānoa students, and others help pinpoint the flows of militarized knowledge—knowledge that is developed by UARCs to strengthen warfighters from within U.S. universities, through the DoD, and to different parts of the world.45

Notes

- ↩ Jake Alimahomed-Wilson et al., “Boeing University: How the California State University Became Complicit in Palestinian Genocide,” Mondoweiss, May 20, 2024; Brian Osgood, “U.S. University Ties to Weapons Contractors Under Scrutiny Amid War in Gaza,” Al Jazeera, May 13, 2024.

- ↩ “Collaborate with Us: University Affiliated Research Center,” DevCom Army Research Laboratory, arl.devcom.army.mil.

- ↩ USC Divest From Death Coalition, “Divest From Death USC News Release,” April 24, 2024.

- ↩ USC Institute for Creative Technologies, “ICT Overview Video,” YouTube, 2:52, December 12, 2023.

- ↩ Gordon Adams and Shoon Murray, Mission Creep: The Militarization of U.S. Foreign Policy?(Washington DC: Georgetown University Press, 2014).

- ↩ USC Institute for Creative Technologies, “ICT Overview Video”; USC Institute for Creative Technologies, Historical Achievements: 1999–2019 (Los Angeles: University of Southern California, May 2021), ict.usc.edu.

- ↩ Yuval Abraham, “‘Lavender’: The AI Machine Directing Israel’s Bombing Spree in Gaza,” +972 Magazine.

- ↩ “UrbanSim,” USC Institute for Creative Technologies.

- ↩ Sylvia J. Martin, “Imagineering Empire: How Hollywood and the U.S. National Security State ‘Operationalize Narrative,’” Media, Culture & Society 42, no. 3 (April 2020): 398–413.

- ↩ Paul Rosenbloom, “Writing the Original UARC Proposal,” USC Institute for Creative Technologies, March 11, 2024.

- ↩ Susannah V. Howieson, Christopher T. Clavin, and Elaine M. Sedenberg, “Federal Security Laboratory Governance Panels: Observations and Recommendations,” Institute for Defense Analyses—Science and Technology Policy Institute, Alexandria, Virginia, 2013, 4.

- ↩ OSD Studies and Federally Funded Research and Development Centers Management Office (FFRDC), Engagement Guide: Department of Defense University Affiliated Research Centers (UARCs) (Alexandria, Virginia: OSD Studies and FFRDC Management Office, April 2013), 5.

- ↩ Christopher V. Pece, “Federal Funding to University Affiliated Research Centers Totaled $1.5 Billion in FY 2021,” National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, National Science Foundation, 2024, ncses.nsf.gov.

- ↩ “UARC Customer Funding Guide,” USC Institute for Creative Technologies, March 13, 2024.

- ↩ “Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFRDC) and University Affiliated Research Centers (UARC),” Department of Defense Research and Engineering Enterprise, rt.cto.mil.

- ↩ OSD Studies and FFRDC Management Office, Engagement Guide.

- ↩ Congressional Research Service, “Federally Funded Research and Development Centers (FFDRCs): Background and Issues for Congress,” April 3, 2020, 5.

- ↩ OSD Studies and FFRDC Management Office, Engagement Guide, 18.

- ↩ “Institute for Creative Technologies (ICT),” USC Military and Veterans Initiatives, military.usc.edu.

- ↩ USC Institute for Creative Technologies, Historical Achievements: 1999–2019, 2; Linda Dayan, “‘Starve the War Machine’: Workers at UC Santa Cruz Strike in Solidarity with Pro-Palestinian Protesters,” Haaretz, May 21, 2024.

- ↩ Richard David Lindholm, That’s a 40 Share!: An Insider Reveals the Origins of Many Classic TV Shows and How Television Has Evolved and Really Works (Pennsauken, New Jersey: Book Baby, 2022).

- ↩ Leo Azambuja, “Faculty Senate Vote Opposing UARC Preserves Freedom,” Mānoa Now, November 30, 2005.

- ↩ Deployment Health Support Directorate, “Fact Sheet: Deseret Test Center, Red Oak, Phase I,” Office of the Assistant Secretary of the Defense (Health Affairs), health.mil.

- ↩ Ray Levy Uyeda, “U.S. Military Activity in Hawai’i Harms the Environment and Erodes Native Sovereignty,” Prism Reports, July 26, 2022.

- ↩ Azambuja, “Faculty Senate Vote Opposing UARC Preserves Freedom.”

- ↩ Kyle Kajihiro, “The Militarizing of Hawai’i: Occupation, Accommodation, Resistance,” in Asian Settler Colonialism, Jonathon Y. Okamura and Candace Fujikane, eds. (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2008), 170–94; “Hearings Officer’s Proposed Decision and Order, Findings of Fact, and Conclusions of Law,” Department of Health, State of Hawai‘i vs. United States Department of the Navy, no. 21-UST-EA-02 (December 27, 2021).

- ↩ Christina Jedra, “Red Hill Depositions Reveal More Details About What the Navy Knew About Spill,” Honolulu Civil Beat, May 31, 2023.

- ↩ “Does Military Sonar Kill Marine Wildlife?,” Scientific American, June 10, 2009.

- ↩ Joan Fuller, “Strategic Outreach—University Affiliated Research Centers,” Office of the Under Secretary of Defense (Research and Engineering), June 2021, 4.

- ↩ DMZ Hawai‘i, “Save Our University, Stop UARC,” dmzhawaii.org.

- ↩ University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Strategic Plan 2002–2010: Defining Our Destiny, 8–9.

- ↩ Craig Gima, “UH to Sign Off on Navy Center,” Star Bulletin, May 13, 2008.

- ↩ University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, “Advocates and Opponents of the Proposed UARC Contract Present Their Case to the UH Board of Regents,” press release, January 23, 2006.

- ↩ Kyle Kajihiro, “The Secret and Scandalous Origins of the UARC,” DMZ Hawai‘i, September 23, 2007.

- ↩ Catherine Lutz, “The Military Normal,” in The Counter-Counterinsurgency Manual, or Notes on Demilitarizing American Society, The Network of Concerned Anthropologists, ed. (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2009).

- ↩ Anne-Laure Fayard and Martina Mendola, “The 3-Stage Process That Makes Universities Prime Innovators,” Harvard Business Review, April 19, 2024; Paul Garton, “Types of Anchor Institution Initiatives: An Overview of University Urban Development Literature,” Metropolitan Universities 32, no. 2 (2021): 85–105.

- ↩ Randall Hill, “ICT Origin Story: How We Built the Holodeck,” Institute for Creative Technologies, February 9, 2024.

- ↩ Brittany Bailer, “Howard University Awarded $90 Million Contract by Air Force, DoD to Establish First-Ever University Affiliated Research Center Led by an HCBU,” The Dig, January 24, 2023, thedig.howard.edu.

- ↩ Erica Caines, “Black University, White Power: Howard University Covers for U.S. Imperialism,” Black Agenda Report, February 1, 2023.

- ↩ Editors, “Howard University: Every Black Thing and Its Opposite, Kwame Ture,” The Black Agenda Review (Black Agenda Report), February 1, 2023.

- ↩ David Vine, Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Abroad Harm America and the World (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2015).

- ↩ USC Divest from Death Coalition, “Divest From Death USC News Release”; “USC Renames VKC, Implements Preliminary Anti-Racism Actions,” Daily Trojan, June 11, 2020.

- ↩ Hopkins Justice Collective, “PIIAC Proposal,” May 4, 2024.

- ↩ Bronson Azama to bor.testimony@hawaii.edu, “Testimony for 2/15/24,” February 15, 2024, University of Hawai’i; “UH Awarded Maui High Performance Computer Center Contract Valued up to $75 Million,” UH Communications, May 1, 2020.

- ↩ Isabel Kain and Becker Sharif, “How UC Researchers Began Saying No to Military Work,” Labor Notes, May 17, 2024.

Feature Image: Deep Space Advanced Radar Capability (DARC) at Johns Hopkins Advanced Physical Laborotory, A UARC facility – www.jhuapl.edu