India’s Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) has recently, through an office memorandum, excluded the new generation genetically modified (GM) plants – also known as genetically edited (GE) plants – from the ambit of India’s biosafety rules. The use of GMO plant seeds like Monsanto’s Bt Cotton gave promising results initially but over a longer period it has resulted in many problems leading to large number of marginal farmer suicides. Based on this bitter experience the Government of India has brought in place very stringent bio-safety rules. However, with new biotech breakthroughs like Genome Editing techniques, there is a huge pressure from corporate giants like Monsanto, Bayer etc to open up agricultural markets in major countries like India and the global south. There is a fear that American capitalism driven biotech companies may destroy indigenous bio-diversities that could result in food insecurity in the long run. India adopted ‘Green Revolution’ in a big way to increase its food production. It lead to the use of High Yield Variety seeds and mono-cultural farming in a big way. Half a century later, there is a need to review the after effects of the ‘Green Revolution’ as the country is plagued by over use of fertilisers, pesticides, water scarcity, increasing salinity, and battling loss of nutrition in farmlands due to the loss of traditional crop diversity. India was home to a vast gene pool of 110000 varieties of native rice before the Green revolution, of which less than 600 are surviving today. The use of GMO crops will lead to further destruction of Indian food diversity. Genome editing, a newer technology, should be examined carefully from a policy perspective. The European Union treats all GMO and GE as one and therefore it has a single stringent policy. Dr Debal Deb has done a pioneering work in saving many of the indigenous rice varieties and campaigns against the industrial agriculture. His is a larger and vital perspective of Agricultural ecology. The Peninsula Foundation revisits his article of 2009 to drive home the importance of preserving and enhancing India’s bio-diversity and agricultural ecology as pressures from capitalist biotech predators loom large for commercial interests.

– TPF Editorial Team

On May 25, 2009, Hurricane Aila hit the deltaic islands of the Sunderban of West Bengal. The estuarine water surged and destroyed the villages. Farmer’s homes were engulfed by the swollen rivers, their properties vanished with the waves, and their means of livelihood disappeared, as illustrated by the empty farm fields, suddenly turned salty. In addition, most of the ponds and bore wells became salinized.

Since Aila’s devastation, there has been a frantic search for the salt-tolerant rice seeds created by the ancestors of the current Sunderban farmers. With agricultural modernization, these heirloom crop varieties had slipped through the farmers’ hands.

But now, after decades of complacency, farmers and agriculture experts alike have been jolted into realizing that on the saline Sunderban soil, modern high-yield varieties are no match for the “primitive,” traditional rice varieties. But the seeds of those diverse salt-tolerant varieties are unavailable now; just one or two varieties are still surviving on the marginal farms of a few poor farmers, who now feel the luckiest. The government rice gene banks have documents to show that they have all these varieties preserved, but they cannot dole out any viable seeds to farmers in need. That is the tragedy of the centralized ex situ gene banks, which eventually serve as morgues for seeds, killed by decades of disuse.

The only rice seed bank in eastern India that conserves salt-tolerant rice varieties in situ is Vrihi, which has distributed four varieties of salt-tolerant rice in small quantities to a dozen farmers in Sunderban. The success of these folk rice varieties on salinized farms demonstrates how folk crop genetic diversity can ensure local food security. These folk rice varieties also promote sustainable agriculture by obviating the need for all external inputs of agrochemicals.

Folk Rice Varieties, the Best Bet

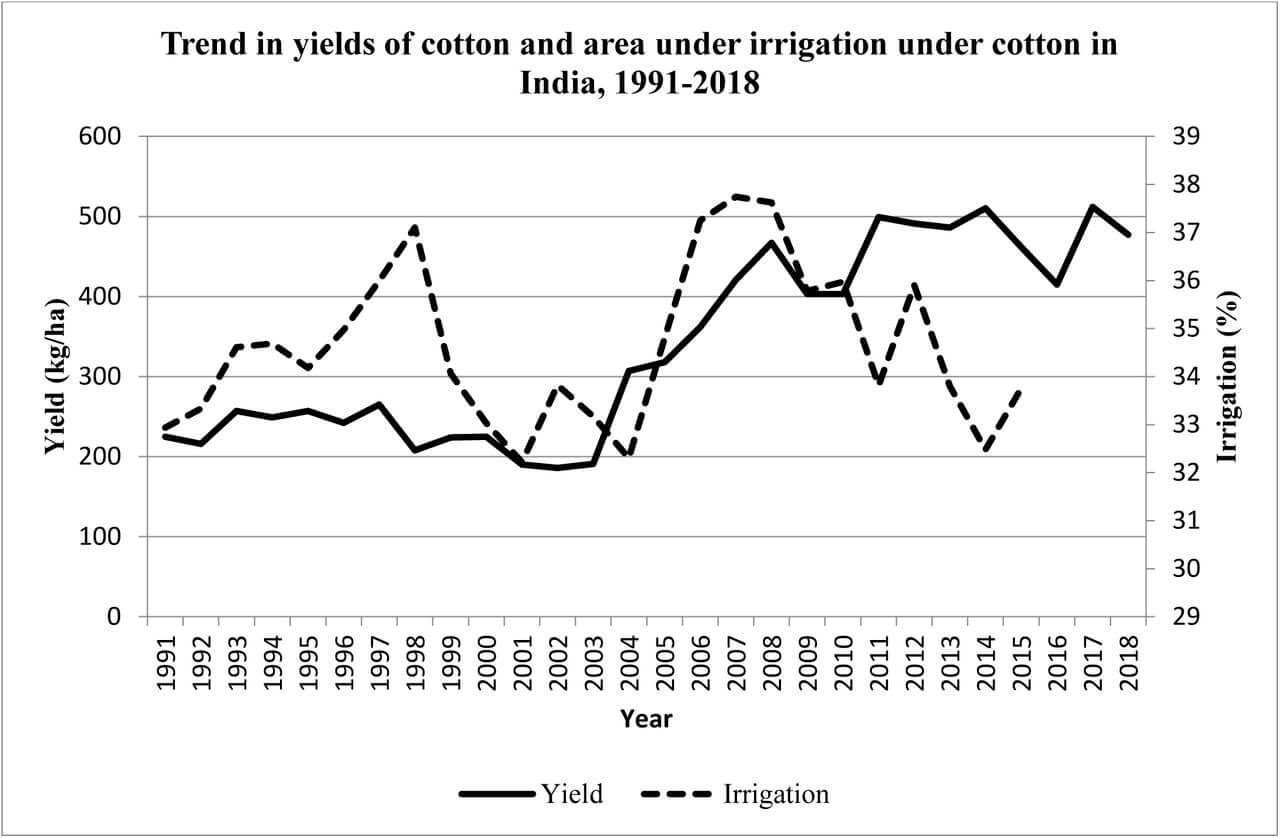

Not only the salinization of soil in coastal farmlands but also the too-late arrival of the monsoon this year has caused seedlings of modern rice varieties to wither on all un-irrigated farms and spelled doom for marginal farmers’ food security throughout the subcontinent. Despite all the brouhaha about the much-hyped Green Revolution, South Asia’s crop production still depends heavily on the monsoon rains and too much, too late, too early, or too scanty rain causes widespread failure of modern crop varieties. Around 60 per cent of India’s agriculture is unirrigated and totally dependent on rain.

In 2002, the monsoon failure in July resulted in a seasonal rainfall deficit of 19 percent and caused a profound loss of agricultural production with a drop of over 3 percent in India’s GDP (Challinor et al. 2006). This year’s shortfall of the monsoon rain is likely to cause production to fall 10 to 15 million tons short of the 100 million tons of total production forecast for India at the beginning of the season (Chameides 2009). This projected shortfall also represents about 3 percent of the expected global rice harvest of 430 million tons.

In the face of such climatic vagaries, modern agricultural science strives to incorporate genes for adaptation — genes that were carefully selected by many generations of indigenous farmer-breeders centuries ago. Thousands of locally-adapted rice varieties (also called “landraces”) were created by farmer selection to withstand fluctuations in rainfall and temperature and to resist various pests and pathogens. Most of these varieties, however, have been replaced by a few modern varieties, to the detriment of food security.

Until the advent of the Green Revolution in the 1960s, India was believed to have been home to about 110,000 rice varieties (Richharia and Govindasamy 1990), most of which have gone extinct from farm fields. Perhaps a few thousand varieties are still surviving on marginal farms, where no modern cultivar can grow. In the eastern state of West Bengal, about 5600 rice varieties were cultivated, of which 3500 varieties of rice were shipped to the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) of the Philippines during the period from 1975 to 1983 (Deb 2005). After an extensive search over the past fourteen years for extant rice varieties in West Bengal and a few neighboring states, I was able to rescue only 610 rice landraces from marginal farms. All others–about 5000–have disappeared from farm fields. The 610 extant rice varieties are grown every year on my conservation farm, Basudha. Every year, these seeds are distributed to willing farmers from the Vrihi seed bank free of charge.

Vrihi (meaning “rice seed” in Sanskrit) is the largest non-governmental seed repository of traditional rice varieties in eastern India. These varieties can withstand a much wider range of fluctuations in temperature and soil nutrient levels as well as water stress than any of the modern rice varieties. This year’s monsoon delay has not seriously affected the survivorship and performance of the 610 rice varieties on the experimental farm, nor did the overabundant rainfall a few years earlier.

Circumstances of Loss

If traditional landraces are so useful, how could the farmers afford to lose them? The dynamics are complex but understandable. When government agencies and seed companies began promoting “miracle seeds,” many farmers were lured and abandoned their heirloom varieties. Farmers saw the initial superior yields of the high input–responsive varieties under optimal conditions and copied their “successful” neighbors. Soon, an increasing number of farmers adopted the modern, “Green Revolution” (GR) seeds, and farmers not participating in the GR were dubbed backward, anti-modern, and imprudent. Seed companies, state agriculture departments, the World Bank, universities, and national and international development NGOs (non-governmental organizations) urged farmers to abandon their traditional seeds and farming practices–both the hardware and software of agriculture. After a few years of disuse, traditional seed stocks became unviable and were thereby lost. Thus, when farmers began to experience failure of the modern varieties in marginal environmental conditions, they had no other seeds to fall back on. Their only option was, and still is, to progressively increase water and agrochemical inputs to the land. In the process, the escalating cost of modern agriculture eventually bound the farmers in an ever-tightening snare of debt. After about a century of agronomists’ faith in technology to ensure food security, farming has become a risky enterprise, with ever greater debt for farmers. Over 150,000 farmers are reported to have committed suicide between 1995 and 2004 in India (Government of India 2007), and the number grew by an annual average of 10,000 until 2007 (Posani 2009).

The government gave ample subsidies for irrigation and fertilizers to convert marginal farms into more productive farms and boosted rice production in the first decade that GR seeds were used. Soon after, however, yield curves began to decline. After 40 years of GR, the productivity of rice is declining at an alarming rate (Pingali 1994). IRRI’s own study revealed yield decreases after cultivation of the “miracle rice variety” IR8 over a 10-year period (Flinn et al 1982). Today, just to keep the land productive, rice farmers in South Asia apply over 11 times more synthetic nitrogen fertilizers and 12.8 times more phosphate fertilizers per hectare than they did in the late 1960s (FAI 2008). Cereal yield has plummeted back to the pre-GR levels, yet many farmers cannot recall that they had previously obtained more rice per unit of input than what they are currently getting. Most farmers have forgotten the average yields of the traditional varieties and tend to believe that all traditional varieties were low-yielding. They think that the modern “high-yielding” varieties must yield more because they are so named.

In contrast, demonstration of the agronomic performance of the 610 traditional rice varieties on Basudha farm over the past 14 years has convinced farmers that many traditional varieties can out-yield any modern cultivar. Moreover, the savings in terms of water and agrochemical inputs and the records of yield stability against the vagaries of the monsoon have convinced them of the economic advantages of ecological agriculture over chemical agriculture. Gradually, an increasing number of farmers have been receiving traditional seeds from the Vrihi seed bank and exchanging them with other farmers. As of this year, more than 680 farmers have received seeds from Vrihi and are cultivating them on their farms. None of them have reverted to chemical farming or to GR varieties.

Extraordinary Heirlooms

Every year, farmer-researchers meticulously document the morphological and agronomic characteristics of each of the rice varieties being conserved on our research farm, Basudha. With the help of simple equipment–graph paper, rulers, measuring tape, and a bamboo microscope (Basu 2007)–the researchers document 30 descriptors of rice, including leaf length and width; plant height at maturity; leaf and internode color; flag leaf angle; color and size of awns; color, shape and size of rice seeds and decorticated grains; panicle density; seed weight; dates of flowering and maturity; presence or absence of aroma; and diverse cultural uses.

Vrihi’s seed bank collection includes numerous unique landraces, such as those with novel pigmentation patterns and wing-like appendages on the rice hull. Perhaps the most remarkable are Jugal, the double-grain rice, and Sateen, the triple-grain rice. These characteristics have been published and copyrighted (Deb 2005) under Vrihi’s name to protect the intellectual property rights of indigenous farmers.

A few rice varieties have unique therapeutic properties. Kabiraj-sal is believed to provide sufficient nutrition to people who cannot digest a typical protein diet. Our studies suggest that this rice contains a high amount of labile starch, a fraction of which yields important amino acids (the building blocks of proteins). The pink starch of Kelas and Bhut moori is an essential nutrient for tribal women during and after pregnancy, because the tribal people believe it heals their anemia. Preliminary studies indicate a high content of iron and folic acid in the grains of these rice varieties. Local food cultures hold Dudh-sar and Parmai-sal in high esteem because they are “good for children’s brains.” While rigorous experimental studies are required to verify such folk beliefs, the prevalent institutional mindset is to discard folk knowledge as superstitious, even before testing it– until, that is, the same properties are patented by a multinational corporation.

Traditional farmers grow some rice varieties for their specific adaptations to the local environmental and soil conditions. Thus, Rangi, Kaya, Kelas, and Noichi are grown on rainfed dryland farms, where no irrigation facility exists. Late or scanty rainfall does not affect the yield stability of these varieties. In flood-prone districts, remarkable culm elongation is seen in Sada Jabra, Lakshmi-dighal, Banya-sal, Jal kamini, and Kumrogorh varieties, which tend to grow taller with the level of water inundating the field. The deepest water that Lakshmi-dighal can tolerate was recorded to be six meters. Getu, Matla, and Talmugur can withstand up to 30 ppt (parts per thousand) of salinity, while Harma nona is moderately saline tolerant. No modern rice variety can survive in these marginal environmental conditions. Traditional crop varieties are often recorded to have out-yielded modern varieties in marginal environmental conditions (Cleveland et al. 2000).

Farmer-selected crop varieties are not only adapted to local soil and climatic conditions but are also fine-tuned to diverse local ecological conditions and cultural preferences. Numerous local rice landraces show marked resistance to insect pests and pathogens. Kalo nunia, Kartik-sal, and Tulsi manjari are blast-resistant. Bishnubhog and Rani kajal are known to be resistant to bacterial blight (Singh 1989). Gour-Nitai, Jashua, and Shatia seem to resist caseworm (Nymphula depunctalis) attack; stem borer (Tryporyza spp.) attack on Khudi khasa, Loha gorah, Malabati, Sada Dhepa, and Sindur mukhi varieties is seldom observed.

Farmers’ agronomic practices, adapting to the complexity of the farm food web interactions, have also resulted in selection of certain rice varieties with distinctive characteristics, such as long awn and erect flag leaf. Peasant farmers in dry lateritic areas of West Bengal and Jharkhand show a preference for long and strong awns, which deter grazing from cattle and goats (Deb 2005). Landraces with long and erect flag leaves are preferred in many areas, because they ensure protection of grains from birds.

Different rice varieties are grown for their distinctive aroma, color, and tastes. Some of these varieties are preferred for making crisped rice, some for puffed rice, and others for fragrant rice sweets to be prepared for special ceremonies. Blind to this diversity of local food cultures and farm ecological complexity, the agronomic modernization agenda has entailed drastic truncation of crop genetic diversity as well as homogenization of food cultures on all continents.

Sustainable Agriculture and Crop Genetic Diversity

Crop genetic diversity, which our ancestors enormously expanded over millennia (Doebley 2006), is our best bet for sustainable food production against stochastic changes in local climate, soil chemistry, and biotic influences. Reintroducing the traditional varietal mixtures in rice farms is a key to sustainable agriculture. A wide genetic base provides “built-in insurance” (Harlan 1992) against crop pests, pathogens, and climatic vagaries.

Traditional crop landraces are an important component of sustainable agriculture because their long-term yield stability is superior to most modern varieties. An ample body of evidence exists to indicate that whenever there is a shortage of irrigation water or of fertilizers–due to drought, social problems, or a disruption of the supply network– “modern crops typically show a reduction in yield that is greater and covers wider areas, compared with folk varieties” (Cleveland et al. 1994). Under optimal farming conditions, some folk varieties may have lower mean yields than high-yield varieties but exhibit considerably higher mean yields in the marginal environments to which they are specifically adapted.

All these differences are amply demonstrated on Basudha farm in a remote corner of West Bengal, India. This farm is the only farm in South Asia where over 600 rice landraces are grown every year for producing seeds. These rice varieties are grown with no agrochemicals and scant irrigation. On the same farm, over 20 other crops, including oil seeds, vegetables, and pulses, are also grown each year. To a modern, “scientifically trained” farmer as well as a professional agronomist, it’s unbelievable that over the past eight years, none of the 610 varieties at Basudha needed any pesticides–including bio-pesticides–to control rice pests and pathogens. The benefit of using varietal mixtures to control diseases and pests has been amply documented in the scientific literature (Winterer et al. 1994; Wolfe 2000; Leung et al. 2003). The secret lies in folk ecological wisdom: biological diversity enhances ecosystem persistence and resilience. Modern ecological research (Folke et al. 2004; Tilman et al. 2006; Allesina and Pascual 2008) supports this wisdom.

If the hardware of sustainable agriculture is crop diversity, the software consists of biodiversity-enhancing farming techniques. The farming technique is the “program” of cultivation and can successfully “run” on appropriate hardware of crop genetic and species diversity. In the absence of the appropriate hardware however, the software of ecological agriculture cannot give good results, simply because the techniques evolved in an empirical base of on-farm biodiversity. Multiple cropping, the use of varietal mixtures, the creation of diverse habitat patches, and the fostering of populations of natural enemies of pests are the most certain means of enhancing agroecosystem complexity. More species and genetic diversity mean greater complexity, which in turn creates greater resilience–that is, the system’s ability to return to its original species composition and structure following environmental perturbations such as pest and disease outbreaks or drought, etc.

Ecological Functions of On-Farm Biodiversity

Food security and sustainability at the production level are a consequence of the agroecosystem’s resilience, which can only be maintained by using diversity on both species and crop genetic levels. Varietal mixtures are a proven method of reducing diseases and pests. Growing companion crops like pigeonpea, chickpea, rozelle, yams, Ipomea fistulosa, and hedge bushes provide alternative hosts for many herbivore insects, thereby reducing pest pressure on rice. They also provide important nutrients for the soil, while the leaves of associate crops like pigeonpea (Cajanus cajan) can suppress growth of certain grasses like Cyperus rotundus.

Pest insects and mollusks can be effectively controlled, even eliminated, by inviting carnivorous birds and reptiles (unless they have been eliminated from the area by pesticides and industrial toxins). Erecting bamboo “T’s” or placing dead tree branches on the farm encourages a range of carnivorous birds, including the drongo, bee eaters, owls, and nightjars, to perch on them. Leaving small empty patches or puddles of water on the land creates diverse ecosystems and thus enhances biodiversity. The hoopoe, the cattle egret, the myna, and the crow pheasant love to browse for insects in these open spaces.

Measures to retain soil moisture to prevent nutrients from leaching out are also of crucial importance. The moisturizing effect of mulching triggers certain key genes that synergistically operate to delay crop senescence and reduce disease susceptibility (Kumar et al. 2004). The combined use of green mulch and cover crops nurtures key soil ecosystem components–microbes, earthworms, ants, ground beetles, millipedes, centipedes, pseudoscorpions, glow worms, and thrips — which all contribute to soil nutrient cycling.

Agricultural sustainability consists of long-term productivity, not short-term increase of yield. Ecological agriculture, which seeks to understand and apply ecological principles to farm ecosystems, is the future of modern agriculture. To correct the mistakes committed in the course of industrial agriculture over the past 50 years, it is imperative that the empirical agricultural knowledge of past centuries and the gigantic achievements of ancient farmer-scientists are examined and employed to reestablish connections to the components of the agroecosystem. The problems of agricultural production that arise from the disintegration of agorecosystem complexity can only be solved by restoring this complexity, not by simplifying it with technological fixes.

Further Reading and Resources: in situ conservation and agroecology

References

Allesina S and Pascual M (2008). Network structure, predator-prey modules, and stability in large food webs. Theoretical Ecology 1(1):55-64.

Basu, P (2007). Microscopes made from bamboo bring biology into focus. Nature Medicine 13(10): 1128. http://www.nature.com/nm/journal/v13/n10/pdf/nm1007-1128a.pdf.

Challinor A, Slingo J, Turner A and Wheeler T (2006). Indian Monsoon: Contribution to the Stern Review. University of Reading. www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/d/Challinor_et_al.pdf.

Chameides B (2009). Monsoon fails, India suffers. The Green Grok. Nicholas School of the Environment at Duke University. www.nicholas.duke.edu/thegreengrok/monsoon_india.

Cleveland DA, Soleri D and Smith SE (1994). Do folk crop varieties have a role in sustainable agriculture? BioScience 44(11): 740–751.

Cleveland DA, Soleri D and Smith SE (2000). A biological framework for understanding farmers’ plant breeding. Economic Botany 54(3): 377–394.

Deb D (2005). Seeds of Tradition, Seeds of Future: Folk Rice Varieties from east India. Research Foundation for Science Technology & Ecology. New Delhi.

Doebley J (2006). Unfallen grains: how ancient farmers turned weeds into crops. Science 312(5778): 1318–1319.

FAI (2008). Fertiliser Statistics, Year 2007-2008. Fertilizer Association of India. New Delhi. http://www.faidelhi.org/

Flinn JC, De Dutta SK and Labadan E (1982). An analysis of long term rice yields in a wetland soil. Field Crops Research 7(3): 201–216.

Folke C, Carpenter S, Walker B, Scheffer M, Elmqvist T, Gunderson L and Holling CS (2004). Regime shifts, resilience and biodiversity in ecosystem management. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 35: 557–581.

Government of India (2007). Report of the Expert Group on Agricultural Indebtedness. Ministry of Agriculture. New Delhi. http://www.igidr.ac.in/pdf/publication/PP-059.pdf

Harlan JR (1992) Crops and Man (2nd edition). , p. 148. American Society of Agronomy, Inc and Crop Science Society of America, Inc., Madison, WI.

Kumar V, Mills DJ, Anderson JD and Mattoo AK (2004). An alternative agriculture system is defined by a distinct expression profile of select gene transcripts and proteins. PNAS 101(29): 10535–10540

Leung H, Zhu Y, Revilla-Molina I, Fan JX, Chen H, Pangga I, Vera Cruz C and Mew TW (2003). Using genetic diversity to achieve sustainable rice disease management. Plant Disease 87(10): 1156–1169.

Pingali PI (1994). Technological prospects for reversing the declining trend in Asia’s rice productivity. In: Agricultural Technology: Policy Issues for the International Community (Anderson JR, ed), pp. 384–401. CAB International.

Posani B (2009). Crisis in the Countryside: Farmer suicides and the political economy of agrarian distress in India. DSI Working Paper No. 09-95. Development Studies Institute, London School of Economics and Political Science. London. http://www.lse.ac.uk/collections/DESTIN/pdf/WP95.pdf

Richharia RH and Govindasamy S (1990). Rices of India. Academy of Development Science. Karjat.

Note: The only reliable data are given in Richharia and Govindasamy (1990), who estimated that about 200,000 varieties existed in India until the advent of the Green Revolution. Assuming many of these folk varieties were synonymous, an estimated 110,000 varieties were in cultivation. Such astounding figures win credibility from the fact that Dr. Richharia collected 22,000 folk varieties (currently in custody of Raipur University) from Chhattisgarh alone – one of the 28 States of India. The IRRI gene bank preserves 86,330 accessions from India [FAO (2003) Genetic diversity in rice. In: Sustainable rice production for food security. International Rice Commission/ FAO. Rome. (web publication) URL: http://www.fao.org/docrep/006/y4751e/y4751e0b.htm#TopOfPage ]

Singh RN (1989). Reaction of indigenous rice germplasm to bacterial blight. National Academy of Science Letters 12: 231-232.

Tilman D, Reich PB and Knops JMH (2006). Biodiversity and ecosystem stability in a decade-long grassland experiment. Nature 441: 629-632.

Winterer J, Klepetka B, Banks J and Kareiva P (1994). Strategies for minimizing the vulnerability of rice to pest epidemics. In: Rice Pest Science and Management. (Teng PS, Heong KL and Moody K, eds.), pp. 53–70. International Rice Research Institute, Manila.

Wolfe MS (2000). Crop strength through diversity. Nature 406: 681–682.

This article was published earlier in Independent Science News and is republished under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License.

Feature Image Credit: www.thebetterindia.com