As is often the case in history, the actions of a dying empire create common ground for its victims to look for new alternatives, no matter how embryonic and contradictory they are. The diversity of support for the expansion of BRICS is an indication of the growing loss of the political hegemony of imperialism.

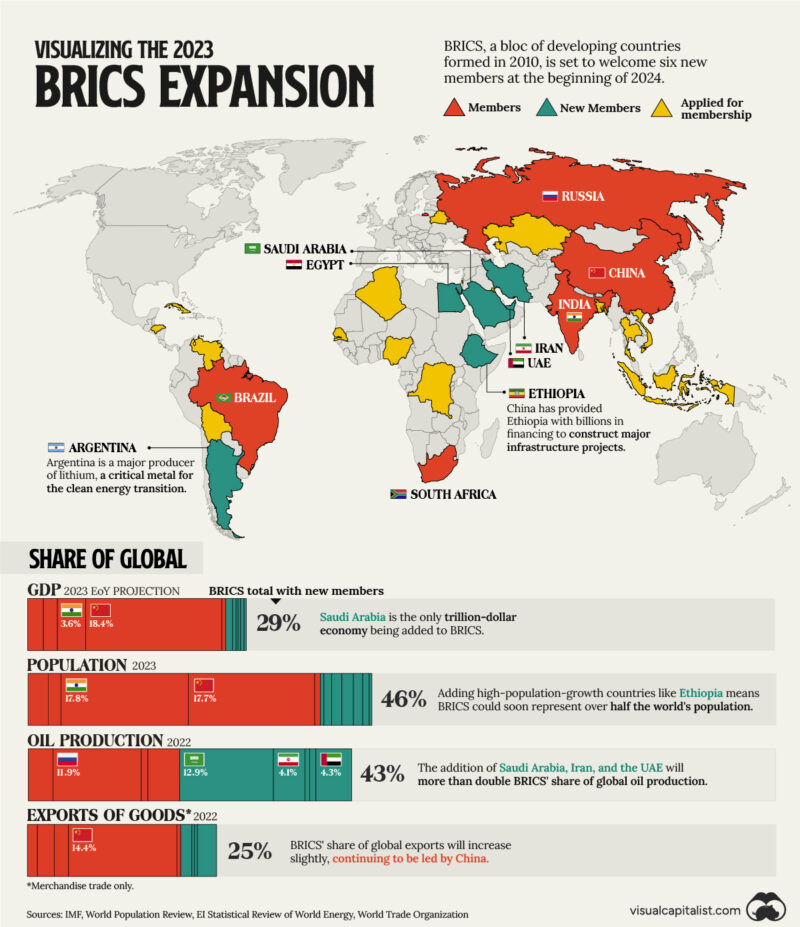

On the last day of the BRICS summit in Johannesburg, South Africa, the five founding states (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa) welcomed six new members: Argentina, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). The BRICS partnership now encompasses 47.3 per cent of the world’s population, with a combined global Gross Domestic Product (by purchasing power parity, or PPP,) of 36.4 per cent. In comparison, though the G7 states (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States) account for merely 10 per cent of the world’s population, their share of the global GDP (by PPP) is 30.4 per cent. In 2021, the nations that today form the expanded BRICS group were responsible for 38.3 percent of global industrial output while their G7 counterparts accounted for 30.5 percent. All available indicators, including harvest production and the total volume of metal production, show the immense power of this new grouping. Celso Amorim, advisor to the Brazilian government and one of the architects of BRICS during his former tenure as foreign minister, said of the new development that ‘[t]he world can no longer be dictated by the G7’.

Certainly, the BRICS nations, for all their internal hierarchies and challenges, now represent a larger share of the global GDP than the G7, which continues to behave as the world’s executive body. Over forty countries expressed an interest in joining BRICS, although only twenty-three applied for membership before the South Africa meeting (including seven of the thirteen countries in the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries, or OPEC). Indonesia, the world’s seventh largest country in terms of GDP (by PPP), withdrew its application to BRICS at the last moment but said it would consider joining later. Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo’s comments reflect the mood of the summit: ‘We must reject trade discrimination. Industrial down streaming must not be hindered. We must all continue to voice equal and inclusive cooperation’.

The facts are clear: the Global North’s percentage of world GDP fell from 57.3 per cent in 1993 to 40.6 per cent in 2022, with the US’s percentage shrinking from 19.7 per cent to only 15.6 per cent of global GDP (by PPP) in the same period – despite its monopoly privilege. In 2022, the Global South, without China, had a GDP (by PPP) greater than that of the Global North.

BRICS does not operate independently of new regional formations that aim to build platforms outside the grip of the West, such as the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States (CELAC) and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). Instead, BRICS membership has the potential to enhance regionalism for those already within these regional fora. Both sets of interregional bodies are leaning into a historical tide supported by important data, analysed by Tricontinental: Institute for Social Research using a range of widely available and reliable global databases. The facts are clear: the Global North’s percentage of world GDP fell from 57.3 per cent in 1993 to 40.6 per cent in 2022, with the US’s percentage shrinking from 19.7 per cent to only 15.6 per cent of global GDP (by PPP) in the same period – despite its monopoly privilege. In 2022, the Global South, without China, had a GDP (by PPP) greater than that of the Global North.

The West, perhaps because of its rapid relative economic decline, is struggling to maintain its hegemony by driving a New Cold War against emergent states such as China. Perhaps the single best evidence of the racial, political, military, and economic plans of the Western powers can be summed up by a recent declaration of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO) and the European Union (EU): ‘NATO and the EU play complementary, coherent and mutually reinforcing roles in supporting international peace and security. We will further mobilise the combined set of instruments at our disposal, be they political, economic, or military, to pursue our common objectives to the benefit of our one billion citizens’.

Why did BRICS welcome such a disparate group of countries, including two monarchies, into its fold? When asked to reflect on the character of the new full member states, Brazil’s President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said, ‘What matters is not the person who governs but the importance of the country. We can’t deny the geopolitical importance of Iran and other countries that will join BRICS’. This is the measure of how the founding countries made the decision to expand their alliance. At the heart of BRICS’s growth are at least three issues: control over energy supplies and pathways, control over global financial and development systems, and control over institutions for peace and security.

A larger BRICS has now created a formidable energy group. Iran, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE are also members of OPEC, which, with Russia, a key member of OPEC+, now accounts for 26.3 million barrels of oil per day, just below thirty per cent of global daily oil production. Egypt, which is not an OPEC member, is nonetheless one of the largest African oil producers, with an output of 567,650 barrels per day. China’s role in brokering a deal between Iran and Saudi Arabia in April enabled the entry of both of these oil-producing countries into BRICS. The issue here is not just the production of oil, but the establishment of new global energy pathways.

The Chinese-led Belt and Road Initiative has already created a web of oil and natural gas platforms around the Global South, integrated into the expansion of Khalifa Port and natural gas facilities at Fujairah and Ruwais in the UAE, alongside the development of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030. There is every expectation that the expanded BRICS will begin to coordinate its energy infrastructure outside of OPEC+, including the volumes of oil and natural gas that are drawn out of the earth. Tensions between Russia and Saudi Arabia over oil volumes have simmered this year as Russia exceeded its quota to compensate for Western sanctions placed on it due to the war in Ukraine. Now these two countries will have another forum, outside of OPEC+ and with China at the table, to build a common agenda on energy. Saudi Arabia plans to sell oil to China in renminbi (RMB), undermining the structure of the petrodollar system (China’s two other main oil providers, Iraq and Russia, already receive payment in RMB).

Both the discussions at the BRICS summit and its final communiqué focused on the need to strengthen a financial and development architecture for the world that is not governed by the triumvirate of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Wall Street, and the US dollar. However, BRICS does not seek to circumvent established global trade and development institutions such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO), the World Bank, and the IMF. For instance, BRICS reaffirmed the importance of the ‘rules-based multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organisation at its core’ and called for ‘a robust Global Financial Safety Net with a quota-based and adequately resourced [IMF] at its centre’. Its proposals do not fundamentally break with the IMF or WTO; rather, they offer a dual pathway forward: first, for BRICS to exert more control and direction over these organisations, of which they are members but have been suborned to a Western agenda, and second, for BRICS states to realise their aspirations to build their own parallel institutions (such as the New Development Bank, or NDB). Saudi Arabia’s massive investment fund is worth close to $1 trillion, which could partially resource the NDB.

BRICS’s agenda to improve ‘the stability, reliability, and fairness of the global financial architecture’ is mostly being carried forward by the ‘use of local currencies, alternative financial arrangements, and alternative payment systems’. The concept of ‘local currencies’ refers to the growing practice of states using their own currencies for cross-border trade rather than relying upon the dollar. Though approximately 150 currencies in the world are considered to be legal tender, cross-border payments almost always rely on the dollar (which, as of 2021, accounts for 40 per cent of flows over the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunications, or SWIFT, network).

Other currencies play a limited role, with the Chinese RMB comprising 2.5 per cent of cross-border payments. However, the emergence of new global messaging platforms – such as China’s Cross-Border Payment Interbank System, India’s Unified Payments Interface, and Russia’s Financial Messaging System (SPFS) – as well as regional digital currency systems promise to increase the use of alternative currencies. For instance, cryptocurrency assets briefly provided a potential avenue for new trading systems before their asset valuations declined, and the expanded BRICS recently approved the establishment of a working group to study a BRICS reference currency.

Following the expansion of BRICS, the NDB said that it will also expand its members and that, as its General Strategy, 2022–2026 notes, thirty per cent of all of its financing will be in local currencies. As part of its framework for a new development system, its president, Dilma Rousseff, said that the NDB will not follow the IMF policy of imposing conditions on borrowing countries. ‘We repudiate any kind of conditionality’, Rousseff said. ‘Often a loan is given upon the condition that certain policies are carried out. We don’t do that. We respect the policies of each country’.

In their communiqué, the BRICS nations write about the importance of ‘comprehensive reform of the UN, including its Security Council’

In their communiqué, the BRICS nations write about the importance of ‘comprehensive reform of the UN, including its Security Council’. Currently, the UN Security Council has fifteen members, five of whom are permanent (China, France, Russia, the UK, and the US). There are no permanent members from Africa, Latin America, or the most populous country in the world, India. To repair these inequities, BRICS offers its support to ‘the legitimate aspirations of emerging and developing countries from Africa, Asia, and Latin America, including Brazil, India, and South Africa to play a greater role in international affairs’. The West’s refusal to allow these countries a permanent seat at the UN Security Council has only strengthened their commitment to the BRICS process and to enhance their role in the G20.

The entry of Ethiopia and Iran into BRICS shows how these large Global South states are reacting to the West’s sanctions policy against dozens of countries, including two founding BRICS members (China and Russia). The Group of Friends in Defence of the UN Charter – Venezuela’s initiative from 2019 – brings together twenty UN member states that are facing the brunt of illegal US sanctions, from Algeria to Zimbabwe. Many of these states attended the BRICS summit as invitees and are eager to join the expanded BRICS as full members.

We are not living in a period of revolutions. Socialists always seek to advance democratic and progressive trends. As is often the case in history, the actions of a dying empire create common ground for its victims to look for new alternatives, no matter how embryonic and contradictory they are. The diversity of support for the expansion of BRICS is an indication of the growing loss of the political hegemony of imperialism.

This article was published earlier in tricontinental.org and is republished under the Creative Commons.