Author: Mr Mohan Guruswamy MA MBA

-

China’s People Crisis

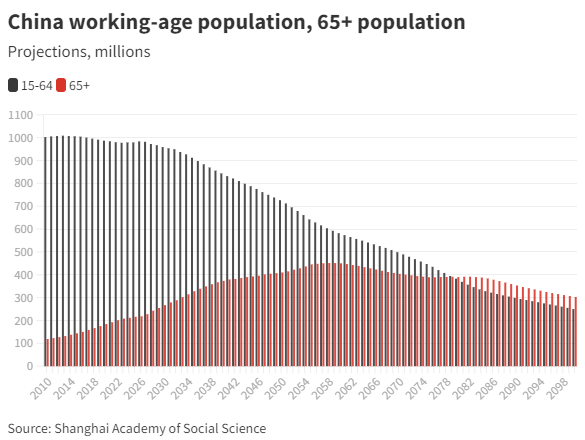

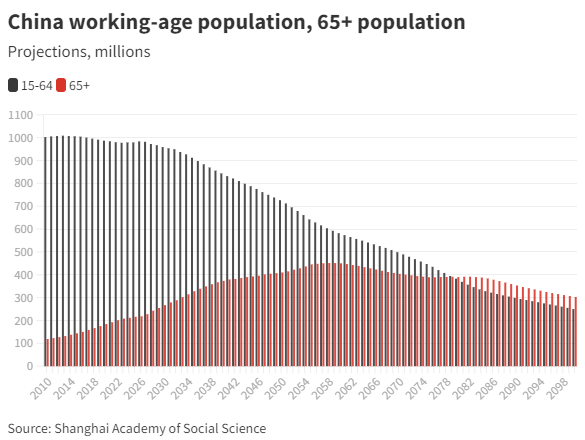

For the first time in sixty years, China’s population has fallen. The population in 2022 – 1.4118 billion – fell by 850,000 from 2021. Its national birth rate has fallen to 6.77 births per thousand people.Deaths have also outnumbered births for the first time last year in China. It logged its highest death rate since 1976 – 7.37 deaths per 1,000 people, up from 7.18 the previous year.China has now hit an impenetrable economic wall. The People’s Republic has a people crisis – it has now stopped growing and is getting old. The reason is paradoxical. China’s one-child policy worked exceedingly well for it in the past. By preventing almost 400 million births since 1979, it gave the Chinese greater prosperity. It is estimated that between 1980 and 2010, the effect of a favourable population age structure accounted for between 15% and 25% of per capita GDP growth.That bonus with the demographic dividend has now ended. China’s population was expected to stabilise in 2030 at 1.391 billion, moving at a slow crawl from 1.330 billion in 2010. But it has hit that spot seven years ahead. In 2050, China is projected to decline to 1.203 billion.The flattening population and its somewhat unfavourable demographic profile have been causing concern in China for some years now. In 2013, the Communist Party of China’s Central Committee allowed couples to have a second child if one parent was an only child. But Chinese families have gotten used to one child existence. The demographic wall is not going to be crossed, and China’s workforce is not growing anymore.Whereas China added as many as 90 million individuals to its workforce from 2005 to 2015, in the decade from 2015, it will, at present trends, add only 5 million. In 2010, there were 116 million people aged 20 to 24. By 2020, the number will fall by 20% to 94 million. The size of the young population aged 20-24 will only be 67 million by 2030, less than 60% of the figure in 2010.One immediate consequence of this slowdown is that by 2030 the cohort aged above 60 years will increase from the present 180 million to 360 million. The other immediate economic consequence is that its savings rate will decline precipitously. As a nation climbs the economic ladder, people inevitably live longer. But old age is also more expensive. For instance, in the US, the old actually consume more than the rest due to medical expenses. Either they support themselves or their families have to support them. Apart from low consumption in the first few years of life, consumption is reasonably constant over the life cycle. But while income is earned and output produced, in the working life between 20 and 65 years, it is not so before and after. This ratio of working-age and non-working-age cohorts is called the dependency ratio.As Indian, African and (surprise, surprise) American dependency ratios turn increasingly favourable in the coming decades, China’s will go downhill and it will join Europe and Japan as the world’s aged societies.In comparison, in 2021, the United States recorded 11.06 births per 1,000 people, and in the United Kingdom, 10.08 births. The birth rate for the same year in India, which is poised to overtake China as the world’s most populous country, was 16.42.China’s total fertility rate – the average number of children born to each woman – is among the lowest in the world, at only 1.4. In contrast, the developed world average is 1.7. China’s replacement rate – the rate at which the number of births and deaths are balanced – is 2.1, as against India’s 2.5. At purchasing power parity, China’s per capita income is just a fifth or less of other large economies. At the same time, China’s fertility level is far below that of the US, UK or France (all around 2.0), and is on par with those of Russia, Japan, Germany and Italy – all countries with sharply declining populations. This is a big reason why Germany so readily accepted to take about a million refugees from Syria and Libya.Over the next 20 years, China’s ratio of workers to retirees will drop precipitously from roughly 5:1 today to just 2:1. Such a big change implies that the tax burden for each working-age person must rise by more than 150%. This assumes that the government will maintain its current level of tax revenue. In addition, mounting expenditure on pensions and healthcare will put China in a difficult position. If the government demands that taxpayers pay more, the public will demand better scrutiny of how their dollars are collected and spent. This could very well open the floodgates of challenges to the Communist Party.Can China succeed to get out of the low growth rate cycle? The conditions now are against it. The cost of rearing a child in China has increased hugely. The state may require more children, but most families will find the costs unaffordable. This is mainly because China is now a predominantly middle-class nation.How will this policy reversal pan out for China? Demographers give three scenarios. The highest outcome will mean 1.43 billion in 2050, while the more plausible outcome will be between 1.35- 1.37 billion. Either way, it is not going to alter the future much for China. It will become old before it becomes rich.Feature Image Credit: ReutersGraph Credit: World Economic Forum

As a nation climbs the economic ladder, people inevitably live longer. But old age is also more expensive. For instance, in the US, the old actually consume more than the rest due to medical expenses. Either they support themselves or their families have to support them. Apart from low consumption in the first few years of life, consumption is reasonably constant over the life cycle. But while income is earned and output produced, in the working life between 20 and 65 years, it is not so before and after. This ratio of working-age and non-working-age cohorts is called the dependency ratio.As Indian, African and (surprise, surprise) American dependency ratios turn increasingly favourable in the coming decades, China’s will go downhill and it will join Europe and Japan as the world’s aged societies.In comparison, in 2021, the United States recorded 11.06 births per 1,000 people, and in the United Kingdom, 10.08 births. The birth rate for the same year in India, which is poised to overtake China as the world’s most populous country, was 16.42.China’s total fertility rate – the average number of children born to each woman – is among the lowest in the world, at only 1.4. In contrast, the developed world average is 1.7. China’s replacement rate – the rate at which the number of births and deaths are balanced – is 2.1, as against India’s 2.5. At purchasing power parity, China’s per capita income is just a fifth or less of other large economies. At the same time, China’s fertility level is far below that of the US, UK or France (all around 2.0), and is on par with those of Russia, Japan, Germany and Italy – all countries with sharply declining populations. This is a big reason why Germany so readily accepted to take about a million refugees from Syria and Libya.Over the next 20 years, China’s ratio of workers to retirees will drop precipitously from roughly 5:1 today to just 2:1. Such a big change implies that the tax burden for each working-age person must rise by more than 150%. This assumes that the government will maintain its current level of tax revenue. In addition, mounting expenditure on pensions and healthcare will put China in a difficult position. If the government demands that taxpayers pay more, the public will demand better scrutiny of how their dollars are collected and spent. This could very well open the floodgates of challenges to the Communist Party.Can China succeed to get out of the low growth rate cycle? The conditions now are against it. The cost of rearing a child in China has increased hugely. The state may require more children, but most families will find the costs unaffordable. This is mainly because China is now a predominantly middle-class nation.How will this policy reversal pan out for China? Demographers give three scenarios. The highest outcome will mean 1.43 billion in 2050, while the more plausible outcome will be between 1.35- 1.37 billion. Either way, it is not going to alter the future much for China. It will become old before it becomes rich.Feature Image Credit: ReutersGraph Credit: World Economic Forum -

BRICS Real Value: One Step Towards New World Order

While “BRICS” has been a frequently occurring acronym in our discourse in recent years, not many seem to have grasped the reality of Brics and its actual utility.

The post-Cold War era has seen the economic and political rise of a host of nations — Brazil, China and India being foremost among them. Since 2000 and the advent of Vladimir Putin, Russia has with some help from soaring oil prices made impressive economic gains. The new South Africa, based equally on the industrial inheritance of the robust but unequal and exploitative apartheid regime and the bounty of nature, now finds itself as an advancing economic power. Unlike Nigeria, which has frittered its oil wealth and has been looted by its native kleptocracy, South Africa has been a relative symbol of responsible government and probity in public life. Each one of these nations is now a major economic player and some already have bigger GDPs than many countries in the Group of Seven. Together, in the next two decades, Brics is likely to outstrip the G-7.

[powerkit_button size=”lg” style=”info” block=”true” url=”https://www.deccanchronicle.com/opinion/columnists/270722/mohan-guruswamy-brics-real-value-one-step-towards-new-world-orde.html” target=”_blank” nofollow=”false”]

Read More

[/powerkit_button] -

India’s Indian Ocean and the Imperative for a Strong Indian Navy

“A good navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace!”The Indian Ocean has been at the centre of world history ever since we know it. Man originated in Africa, probably somewhere in the Olduvai Gorge in present-day Tanzania – where Homo Erectus lived 1.2 million years ago and where the first traces of Homo Sapiens, our more recent ancestors having evolved only about 200,000 years ago. First phonetic languages evolved around 100, 000 years ago. The migration of mankind out of Africa began almost 60000 years ago. But we don’t call the Indian Ocean the African Ocean because the first recorded activity over it began only about 3000 years ago.Three great early recorded activities of this period come to mind. The first is the Indus Valley Civilization. It was a Bronze Age civilization (3300–1300 BCE; mature period 2600–1900 BCE) in the northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. Along with Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia, it was one of three early civilizations of the Old World, and of the three the most widespread.The Indus civilization’s economy appears to have depended significantly on trade, which was facilitated by major advances in transport technology. It may have been the first civilization to use wheeled transport. These advances may have included bullock carts that are identical to those seen throughout South Asia today, as well as boats. Most of these boats were probably small, flat-bottomed craft, perhaps driven by sail, similar to those one can see on the Indus River today; however, there is secondary evidence of sea-going craft.Archaeologists have discovered a massive, dredged canal and what they regard as a docking facility at the coastal city of Lothal now in Gujarat. Judging from the dispersal of Indus civilization artifacts, the trade networks, economically, integrated a huge area, including portions of Afghanistan, the coastal regions of Persia, northern and western India, and Mesopotamia. There is some evidence that trade contacts extended to Crete and possibly to Egypt.There was an extensive maritime trade network operating between the Harappan and Mesopotamian civilizations as early as the middle Harappan Phase, with much commerce being handled by “middlemen merchants from Dilmun” (modern Bahrain and Failaka located in the Persian Gulf). Such long-distance sea trade became feasible with the innovative development of plank-built watercraft, equipped with a single central mast supporting a sail of woven rushes or cloth.The second great economic activity was Slavery. Slavery can be traced back to the earliest records, such as the Code of Hammurabi (c. 1760 BC), which refers to it as an established institution. Slavery is rare among hunter-gatherer populations, as it is developed as a system of social stratification. Slavery typically also requires a shortage of labour and a surplus of land to be viable. Bits and pieces from history indicate that Arabs enslaved over 150 million African people and at least 50 million from other parts of the world. Later they also converted Africans into Islam, causing a complete social and financial collapse of the entire African continent apart from wealth attributed to a few regional African kings who became wealthy in the trade and encouraged it.The third great economic activity was seafaring evidenced by migration. The island of Madagascar, the largest in the Indian Ocean, lies some 250 miles (400 km) from Africa and 4000 miles (6400 km) from Indonesia. New findings, published in the American Journal of Human Genetics, show that the human inhabitants of Madagascar are unique – amazingly, half of their genetic lineages derive from settlers from the region of Borneo, with the other half from East Africa. It is believed that the migration from the Sunda Islands began around 200 BC.Linguists have established that the origins of the language spoken in Madagascar, Malagasy, suggested Indonesian connections, because its closest relative is the Maanyan language, spoken in southern Borneo. The Gods were also kind and gave the IOR the weather conditions that helped in evolving seaborne trade and intercourse. The sea surface current and prevailing wind structure in and over the Indian Ocean favoured seafarers in their endeavour and sailings in the Indian Ocean from the southern tip of Africa (Cape of Good Hope) during the month of May. After the entry into the Indian Ocean, the seafarers continued to sail in the northerly direction along the coastline of Africa (aided by the strong Somali Current and the East Arabian Current) towards the Arabian Sea.The physical environmental conditions over the sea and the external prevailing weather helped the seafarers reach places up to the west coast of India. As this sea surface current extend towards the east coast of India, the sailors were greatly assisted by the surface current as they sailed along. During November, when the East Indian Winter wind reverses in its direction and begins to blow from the northeast, the sailors prepare for their return journey. The winds that generate the waves contribute to the reduction in the otherwise required travel time for the sailings between any given two points of departure and arrival. The natural and external forces help the sailors make their journey/expedition more economical and energy-efficient.Clearly, the region was a hub of all kinds of economic activity. Then came the Petroleum Age. And things changed as never before. The Spice trade, the Silk trade, and the China trade all paled into insignificance. The use of Coal as a ship fuel enlarged distances and volumes of cargo. Oil made even longer journeys and greater volumes possible.Petroleum is the lifeblood of modern society. It’s a relatively new activity, but its advent has transformed our world as few things have. Petroleum, in one form or another, has been used since ancient times. According to Herodotus more than 4000 years ago, asphalt was used in the construction of the walls and towers of Babylon; there were oil pits near Babylon, and a pitch spring on Zacynthus.Great quantities of it were found on the banks of the river Issus, one of the tributaries of the Euphrates. Ancient Persian tablets indicate the medicinal and lighting uses of petroleum in the upper levels of their society. By 347 AD, oil was produced from bamboo-drilled wells in China. Early British explorers to Myanmar documented a flourishing oil extraction industry based in Yenangyaung, that in 1795 had hundreds of hand-dug wells under production.Oil is now the single most important driver of world economics, politics and technology. The rise in importance was due to the invention of the internal combustion engine, the rise in commercial aviation, and the importance of petroleum to industrial organic chemistry, particularly the synthesis of plastics, fertilizers, solvents, adhesives and pesticides. Today, oil contributes 3% of the global GDP.In 1847, the process to distill kerosene from petroleum was invented by James Young. He noticed natural petroleum seepage in the Riddings colliery at Alfreton, Derbyshire from which he distilled a light thin oil suitable for use as lamp oil, at the same time obtaining a thicker oil suitable for lubricating machinery. In 1848 Young set up a small business refining the crude oil.Today the world’s biggest stand-alone refinery is the Reliance refinery at Jamnagar with a refining capacity of about 1.5 million barrels a day. The Essar refinery at Jamnagar refines a further 0.5 million barrels a day. Together they make Jamnagar one of the world’s great refining centers. India’s number one export item is Petroleum products, mostly Petrol and Diesel. India now exports the equivalent of about 615,000 barrels a day. In 2020, petroleum exports accounted for $25.3 billion of our total exports of $291.8 billion in the same year.India imported $77 billion worth of oil in the year 2020-21 and more than half of this comes from countries in the IOR. Iraq’s share is 22.4%, Saudi Arabia’s share is 18.8%, UAE’s share is 10.8%, and Kuwait’s 5%. The IOR is India’s lifeline and lifeblood. If the line is blocked we will suffer hugely, if the blood gets anaemic we will suffer hugely. India just cannot afford anything to go wrong here.The sea lanes in the Indian Ocean are considered among the most strategically important in the world—according to the Journal of the Indian Ocean Region, more than 80 percent of the world’s seaborne trade in oil transits through the Indian Ocean choke points, with 40 percent passing through the Strait of Hormuz, 35 percent through the Strait of Malacca and 8 percent through the Bab el-Mandab Strait.But it’s not just about sea-lanes and trade. More than half the world’s armed conflicts are presently located in the Indian Ocean region, while the waters are also home to continually evolving strategic developments including the competing rises of China and India, the potential nuclear confrontation between India and Pakistan, the US interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, Islamist terrorism, incidents of piracy in and around the Horn of Africa, and management of diminishing fishery resources.As a result of all this, almost all the world’s major powers have deployed substantial military forces in the Indian Ocean region. For example, in addition to maintaining expeditionary forces in Iraq, the US 5th Fleet is headquartered in Bahrain, and uses the island of Diego Garcia as a major air-naval base and logistics hub for its Indian Ocean operations. In addition, the United States has deployed several major naval task forces there, including Combined Task Force 152 (currently operated by the Kuwait Navy), which is focusing on illicit non-state actors in the Arabian Gulf, and Combined Task Force 150 (currently commanded by the Pakistan Navy), which is tasked with Maritime Security Operations (MSO) outside the Arabian Gulf with an Area of Responsibility (AOR) covering the Red Sea, Gulf of Aden, Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Oman. France, meanwhile, is perhaps the last of the major European powers to maintain a significant presence in the north and southwest Indian Ocean quadrants, with naval bases in Djibouti, Reunion, and Abu Dhabi.And, of course, China and India both also have genuine aspirations of developing blue water naval capabilities through the development and acquisition of aircraft carriers and an aggressive modernization and expansion programme.China’s aggressive soft power diplomacy has widely been seen as arguably the most important element in shaping the Indian Ocean strategic environment, transforming the entire region’s dynamics. By providing large loans on generous repayment terms, investing in major infrastructure projects such as the building of roads, dams, ports, power plants, and railways, and offering military assistance and political support in the UN Security Council through its veto powers, China has secured considerable goodwill and influence among countries in the Indian Ocean region.And the list of countries that are coming within China’s strategic orbit appears to be growing. Sri Lanka, which has seen China replace Japan as its largest donor, is a case in point—China was no doubt instrumental in ensuring that Sri Lanka was granted dialogue partner status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO).To the west, Kenya offers another example of how China has been bolstering its influence in the Indian Ocean. The shift was underscored in a leaked US diplomatic cable from February 2010 that was recently published by WikiLeaks. In it, US Ambassador to Kenya Michael Ranneberger highlighted the decline of US influence in East Africa’s economic hub, saying: ‘We expect China’s engagement in Kenya to continue growing given Kenya’s strategic location…If oil or gas is found in Kenya, this engagement will likely grow even faster. Kenya’s leadership may be tempted to move close to China in an effort to shield itself from Western, and principally US pressure to reform.’The rise of China as the world’s greatest exporter, its largest manufacturing nation and its great economic appetite poses a new set of challenges. At a meeting of South-East Asian nations in 2010, China’s foreign minister Yang Jiechi, facing a barrage of complaints about his country’s behaviour in the region, blurted out the sort of thing polite leaders usually prefer to leave unsaid. “China is a big country,” he pointed out, “and other countries are small countries and that is just a fact.”Indeed it is, and China is big not merely in terms of territory and population, but also in military might. Its Communist Party is presiding over the world’s largest military build-up. And that is just a fact, too—one that the rest of the world has to come to terms with.China’s defence budget has almost certainly experienced double-digit growth for two decades. According to SIPRI, a research institute, annual defence spending rose from over $30 billion in 2000, $120 billion in 2010 to almost $229.4 billion in 2021. SIPRI usually adds about 50% to the official figure that China gives for its defence spending, because even basic military items such as research and development are kept off budget. Including those items would imply total military spending in 2021, based on the latest announcement from Beijing, would be around $287.8 billion.This is not a sum India can match and the last thing we need to get caught in is a numbers game. A one-party dictatorship will always be able to outspend us, even if our GDPs get closer.But history tells us again and again that victory is not assured by superiority in numbers and even technology. If that were to be so, Alexander should have been defeated at Gaugamela, Babur at Panipat, Wellington at Waterloo, Russia at Leningrad, Britain in the Falklands, and above all Vietnam who defeated three of the world’s leading powers – France, the USA and China – in succession. I don’t have to tell you that victory is more a result of strategy and tactics. Numbers do matter, but numbers are not all. Technology does matter, but technology alone cannot assure you of victory. It’s always mind over matter. You know these things better than most of us. You also know what to do. As the old saying goes: “When the going gets tough, the tough get going!”That said, the threat from China should not be exaggerated. There are three limiting factors. First, unlike the former Soviet Union, China has a vital national interest in the stability of the global economic system. Its military leaders constantly stress that the development of what is still only a middle-income country with a lot of very poor people takes precedence over military ambition. The increase in its military spending reflects the growth of the economy, rather than an expanding share of national income. For many years China has steadily spent the same proportion of GDP on defence (a bit over 1.7%, whereas America spend about 3.7% in the year 2020-21).The real test of China’s willingness to keep military spending constant will come when China’s headlong economic growth starts to slow further. But in the past form, China’s leaders will continue to worry more about internal threats to their control than external ones. In 2020, the Chinese spending on internal security was $212 billion. With a rapidly ageing population, it is also a good bet that meeting the demand for better health care will become a higher priority than maintaining military spending.Like all the other great powers, China faces a choice of guns and butter or more appropriately walking sticks. But till then it is: Nervi belli pecunia infinita or unlimited money is the muscle of war.India on the other hand will keep growing long after China has stopped growing. Its youthful population and present growth trends indicate the accumulation of the world’s largest middle class in India. India’s growth is projected to continue well past 2050. In fact so big will this become, that India during this period will increasingly power world economic growth, and not China. In 2050, India is projected to have a population of 1.64 billion and of these 1.3 billion will belong to the middle and upper classes. The lower classes will be constant at around 300 million, as it is now.India already has the world’s third-largest GDP. Many economists prophesize that in 2050 it will be India that will be the world’s biggest economy, not China. In per capita terms, we might still be poorer, but in over GDP terms, we will be bigger.According to a study by IHS Markit, a subsidiary of S&P Global, India will be the world’s third-largest economy by 2030. Indian GDP in 2030 is projected to be $8.4 trillion. China, in second place, will have a GDP of $ 33.7 trillion and the US $ 30.4 trillion. As we say in India, aap key muh mein ghee aur shakhar. Both incidentally now deemed bad for health.Now comes the dilemma for India. Robert Kaplan writes: “As the United States and China become great power rivals, the direction in which India tilts could determine the course of geo-politics in Eurasia in the 21st century. India, in other words, looms at the ultimate pivot state.” At another time Mahan noted that India, located in the centre of the Indian Ocean littoral, is critical for the seaward penetration of both the Middle-east and China.Now if one were an Indian planner, he or she would be looking at the China Pakistan axis with askance. India has had conflicts and still perceives threats from both, jointly and severally. The Tibetan desert, once intended to be India’s buffer against the north now has become China’s buffer against India. The planner will not be looking at all if he or she were not looking at the Indian Ocean as a theatre. After all, it is also China’s lifeline and its lifeblood flows here.Now if one were a Chinese planner, he or she would be looking with concern over India’s growth and increasing ability to project power in the IOR. The planner will also note what experts are saying about India’s growth trajectory. That it will be growing long after China gets walking sticks. That it is the ultimate pivot state in the grand struggle for primacy between the West led by the USA and Japan, and China.What will this planner be thinking particularly given the huge economic and military asymmetry between China and India now? Tacitus tells it most pithily. That peace can come through strength or Si vis pacem para bellum. While China has ratcheted up its show of assertiveness in recent years, India has been quietly preparing for a parity to prevent war. Often parity does not have to be equality in numbers. The fear of pain disproportionate to the possible gains, and the ability of the smaller in numbers side to do so in itself confer parity.There is a certain equilibrium in Sino-Indian affairs that make recourse to force extremely improbable. Both modern states are inheritors of age-old traditions and the wisdom of the ages. Both now read their semaphores well and know how much of the sword must be unsheathed to send a message. This ability will ensure the swords remain recessed and for the plowshares to be out at work.Finally, I would be remiss if I did not say something about the centrality of the Indian Navy to our future. Nothing says it better than what Theodore Roosevelt said a century ago: “A good Navy is not a provocation to war. It is the surest guarantee of peace!”Featured Image Credit: Indian Navy -

India’s Agriculture: The Failure of the Success

It was around the mid-1960s when the Paddock brothers, Paul and William, the ‘prophets of doom’, predicted that in another decade, recurring famines and an acute shortage of food grains would push India towards disaster. Stanford University Professor Paul R. Ehrlich in his 1968 best selling book The Population Bomb warned of the mass starvation of humans in the 1970s and 1980s in countries like India due to over population.

Their prophecies were based on a rising shortage of food because of droughts, which forced India to import 10 million tonnes of grain in 1965-66 and a similar amount a year before. Little did they know that thanks to quick adoption of a new technology by Indian farmers, the country would more than double its annual wheat production from 11.28 million tonnes in 1962-63 to more than twice that within ten years to 24.99 million tonnes. It was 71.26 million tonnes in 2007. Similarly rice production also grew spectacularly from 34.48 million tonnes to almost 90 million tonnes in 2007.

Total food grains production in India reached an all-time high of 251.12 million tonnes (MT) in FY15. Rice and wheat production in the country stood at 102.54 MT and 90.78 MT, respectively. India is among the 15 leading exporters of agricultural products in the world. The value of which was Rs.1.31 lakh crores in FY15.

India is among the 15 leading exporters of agricultural products in the world. The value of which was Rs.1.31 lakh crores in FY15.

Despite its falling share of GDP, agriculture plays a vital role in India’s economy. Over 58 per cent of the rural households depend on agriculture as their principal means of livelihood. Census 2011 says there are 118.9 million cultivators across the country or 24.6 per cent of the total workforce of over 481 million. In addition there are 144 million persons employed as agricultural laborers. If we add the number of cultivators and agricultural laborers, it would be around 263 million or 22 percent of the population. As per estimates by the Central Statistics Office (CSO), the share of agriculture and allied sectors (including agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishery) was 16.1 per cent of the Gross Value Added (GVA) during 2014–15 at 2011–12 prices. This about sums up what ails our Agriculture- its contribution to the GDP is fast dwindling, now about 13.7 per cent, and it still sustains almost 60 per cent of the population.

If we add the number of cultivators and agricultural laborers, it would be around 263 million or 22 percent of the population. As per estimates by the Central Statistics Office (CSO), the share of agriculture and allied sectors (including agriculture, livestock, forestry and fishery) was 16.1 per cent of the Gross Value Added (GVA) during 2014–15 at 2011–12 prices.

With 157.35 million hectares, India holds the world’s second largest agricultural land area. India has about 20 agro-climatic regions, and all 15 major climates in the world exist here. Consequently it is a large producer of a wide variety of foods. India is the world’s largest producer of spices, pulses, milk, tea, cashew and jute; and the second largest producer of wheat, rice, fruits and vegetables, sugarcane, cotton and oilseeds. Further, India is 2nd in global production of fruits and vegetables, and is the largest producer of mango and banana. It also has the highest productivity of grapes in the world. Agricultural export constitutes 10 per cent of the country’s exports and is the fourth-largest exported principal commodity.

According to the Agriculture Census, only 58.1 million hectares of land was actually irrigated in India. Of this 38 percent was from surface water and 62 per cent was from groundwater. India has the world’s largest groundwater well equipped irrigation system.There is a flipside to this great Indian agriculture story.The Indian subcontinent boasts nearly half the world’s hungry people. Half of all children under five years of age in South Asia are malnourished, which is more than even sub-Saharan Africa.

More than 65 per cent of the farmland consists of marginal and small farms less than one hectare in size. Moreover, because of population growth, the average farm size has been decreasing. The average size of operational holdings has almost halved since 1970 to 1.05 ha. Approximately 92 million households or 490 million people are dependent on marginal or small farm holdings as per the 2001 census. This translates into 60 per cent of rural population or 42 per cent of total population.

Approximately 92 million households or 490 million people are dependent on marginal or small farm holdings as per the 2001 census.

About 70 per cent of India lives in rural areas and all-weather roads do not connect about 40 per cent of rural habitations. Lack of proper transport facility and inadequate post harvesting methods, food processing and transportation of foodstuffs has meant an annual wastage of Rs. 50,000 crores, out of an out of about Rs.370, 000 crores.

There is a pronounced bias in the government’s procurement policy, with Punjab, Haryana, coastal AP and western UP accounting for the bulk (83.51 per cent) of the procurement. The food subsidy bill has increased from Rs. 24500 crores in 1990-91 to Rs. 1.75 lakh crores in 2001-02 to Rs. 2.31 lakh crores in 2016. Instead of being the buyer of last resort FCI has become the preferred buyer for the farmers. The government policy has resulted in mountains of food-grains coinciding with starvation deaths. A few regions of concentrated rural prosperity.

The total subsidy provided to agricultural consumers by way of fertilizers and free power has quadrupled from Rs. 73000 crores in 1992-93, to Rs. 3.04 lakh crores now. While the subsidy was launched to reach the lower rung farmers, it has mostly benefited the well-off farmers. Free power has also meant a huge pressure on depleting groundwater resources.

These huge subsidies come at a cost. Thus, public investment in agriculture, in real terms, had witnessed a steady decline from the Sixth Five-Year Plan onwards. With the exception of the Tenth Plan, public investment has consistently declined in real terms (at 1999-2000 prices) from Rs.64, 012 crores during the Sixth Plan (1980-85) to Rs 52,107 crores during the Seventh Plan (1985-90), Rs 45,565 crores during the Eighth Plan (1992-97) and about Rs 42,226 crores during Ninth Plan (1997-2002).With the exception of the Tenth Plan, public investment has consistently declined in real terms (at 1999-2000 prices) from Rs.64, 012 crores during the Sixth Plan (1980-85) to Rs 52,107 crores during the Seventh Plan (1985-90), Rs 45,565 crores during the Eighth Plan (1992-97) and about Rs 42,226 crores during Ninth Plan (1997-2002).

Share of agriculture in total Gross Capital Formation (GCF) at 93-94 prices has halved from 15.44 per cent to 7.0 per cent in 2000-01. In 2001-02 almost half of the amount allocated to irrigation was actually spent on power generation. While it makes more economic sense to focus on minor irrigation schemes, major and medium irrigation projects have accounted for more than three fourth of the planned funds

By 2050, India’s population is expected to reach 1.7 billion, which will then be equivalent to nearly that of China and the US combined. A fundamental question then is can India feed 1.7 billion people properly? In the four decades starting 1965-66, wheat production in Punjab and Haryana has risen nine-fold, while rice production increased by more than 30 times. These two states and parts of Andhra Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh now not only produce enough to feed the country but to leave a significant surplus for export.Since food production is no longer the issue, putting economic power into the hands of the vast rural poor becomes the issue. The first focus should be on separating them from their smallholdings by offering more gainful vocations.

Farm outputs in India in recent years have been setting new records. It has gone up from 208 MT in 2005-06 to an estimated 251 MT in 2014-15. Even accounting for population growth during this period, the country would need probably around 225 to 230 MT to feed its people. There is one huge paradox implicit in this. Record food production is depressing prices. No wonder farmers with marketable surpluses are restive.

India is producing enough food to feed its people, now and in the foreseeable future. Since food production is no longer the issue, putting economic power into the hands of the vast rural poor becomes the issue. The first focus should be on separating them from their smallholdings by offering more gainful vocations. With the level of skills prevailing, only the construction sector can immediately absorb the tens of millions that will be released. Government must step up its expenditures for infrastructure and habitations to create a demand for labor. The land released can be consolidated into larger holdings by easy credit to facilitate accumulation of smaller holdings to create more productive farms.

Finally the entire government machinery geared to controlling food prices to satisfy the urban population should be dismantled. If a farmer has to buy a motorcycle or even a tractor he pays globally comparative prices, why should he make food available to the modern and industrial sector at the worlds lowest prices?

Why should Bharat have to feed India at its cost?Image: Kanyakumari farm lands during onset of monsoon.

-

Think tanks’ role growing: Is that a good thing?

Category : Education/Think tanks/Policy Research

Title : Think tank’s role growing: Is that a good thing?

Author : Mohan Guruswamy 20.01.2020

The word “think tank” owes its origins to John F. Kennedy, America’s 35th President, who collected a group of top intellectuals in his White House – people like McGeorge Bundy, Robert S. McNamara, John Kenneth Galbraith, Arthur Schlesinger and Ted Sorenson, among others, to give him counsel on issues from time to time. In India, while the number of think tanks are now increasing, neither the government nor the think tanks have a culture of serious and in-depth research that would aid government’s policy making. Mohan Guruswamy analyses the think tanks and their culture in India.

Read More

-

Winds of Climate Change Blow across South Asia

The India-Pakistan enmity is possibly the world’s most intractable and obdurate, with a mutual misreading of history made extremely volatile with the brandishing of nuclear weapons. Despite having two giant militaries at each others’ throats, the more immediate existential challenges that India and Pakistan face are related to how climate change and misuse of common natural resources have combined to confront both together. It is not the militaries which will determine our fates, but the degree of cooperation the two nations can summon. Our problems are common and perhaps India and Pakistan will find the good sense to act together?

Looking at the climate change challenges Pakistan and India face together, collective action — as unlikely as it seems — may just be what is needed to secure the lives and livelihoods of future generations.

According to climate researchers at Germanwatch, Pakistan ranks eighth on the Global Climate Risk Index, with over 145 catastrophic events — heat waves, droughts and floods — reported in the past 20 years. On the other hand, India ranks among the top 20 vulnerable countries in terms of climate risk. Pakistan is home to around 47 per cent of the Indus Basin, and India to around 39 per cent. The Indus Waters Treaty has been in effect since 1960. The recent political bickering aside, the Indus Waters Treaty has managed to survive the test of time, yet fails to comprehensively address climate change. Then again, at the time it was enacted, many of the stark realities we know today were not understood.

According to the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources, Pakistan officially crossed the water scarcity line in 2005. The United Nations Development Programme and the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources have issued warnings about the upcoming scarcity of groundwater in just six years.

According to some estimates, Pakistan is the fourth-largest user of its groundwater and over 70 per cent of drinking requirements and 50 per cent of irrigation needs are met through groundwater extraction. Due to excessive pumping, it is estimated that water tables could fall by as much as 20 per cent by 2025.

South Asia is drained by the Indus, Ganga and Brahmaputra river basins, which collectively form the Indo-Gangetic Basin (IGB) and include some of the highest-yielding aquifers of the world. The aquifers associated with these river basins cross the international borders of the contiguous South Asian countries, forming numerous trans-boundary aquifers, including the Indus basin aquifers (between India and Pakistan), Ganga and Brahmaputra basin aquifers (between Bangladesh and India), the aquifers of the tributaries to the Ganga (between Nepal and India), the aquifers of the tributaries to the Brahmaputra (between Bhutan and India, and between India and Bangladesh).

At the beginning of every hydrologic year, 4,000 billion cubic meters (bcm) water enters the South Asian hydrological systems, of which almost half is lost by poorly understood and un-quantified processes (such as overland flow, surface discharge through rivers to the oceans, submarine groundwater discharge and evaporation). The annual groundwater withdrawals in the region are estimated to exceed 340 bcm, and represent the most voluminous use of groundwater in the world. South Asia faces an acute shortage of drinking water and other usable waters in many areas, as it is seeing a rapid rise in water demand and change in societal water use pattern because of accelerated urbanisation and changes in lifestyle. In many urban and rural areas of the region, surface waters have been historically used as receptacles of sewage and industrial waste, rendering them unfit for domestic use, prompting a switch to groundwater and rainwater sources to meet drinking and agricultural water needs. At present, about 60–80 per cen

t of the domestic water supplies across South Asia are met by groundwater.Irrigation accounts for 85 per cent of groundwater withdrawals and is considered to be the main contributor to groundwater depletion with the maximum possible groundwater footprint seen in the Gangetic aquifers.

Among the main contributors to water stress in India and Pakistan are poor water resource management and poor water service delivery, including irrigation and drainage services. Moreover, the lack of reliable water data, subsequent analysis and consequent poor planning and allocation is leading to environmentally unviable methods of water withdrawal, causing an alarming reduction in groundwater.

In both countries, water stress is attributed first and foremost to the massive population growth. Another cause is the lack of sufficient urban water treatment facilities, which prevent the usability of river water for drinking and irrigation.

Air pollution contributes substantially to premature mortality and disease burden globally, with a greater impact in low-income and middle-income countries than in high-income countries. The northern plains of South Asia has one of the highest exposure levels to air pollution globally.

The major components of air pollution are ambient particulate matter pollution, household air pollution, and to a smaller extent ozone in the troposphere, the lowest layer of atmosphere. The major sources of ambient particulate matter pollution are coal burning for thermal power production, industry emissions, construction activity and brick kilns, transport vehicles, road dust, residential and commercial biomass burning, waste burning, agricultural stubble burning, and diesel generators.

In India and Pakistan, farm residues are burnt after harvesting in October to November, which affects the air quality of the region. In Pakistan, most of the rice cultivation takes place in Punjab, and the same is true for India’s Punjab due to suitable climatic conditions for the crop. In both countries, stubble burning is the key cause of smog. According to India’s new and renewable energy sources ministry, India’s Punjab contributes 44-51 million tonnes of residue annually. According to the estimates, paddy areas burnt every year in Indian Punjab and Haryana are 12.68 million hectares and 2.08 million hectares respectively. According to a study, farmers burn 30-90 per cent of residue, which contributes to the smog formation, not just in the immediate region, but the entire Indo-Gangetic plain. With air pollution levels lurking in the “extremely poor” band for almost half the year, the northern regions of South Asia may not be able to host healthy populations for very long.

The number of deaths attributable to ambient particulate matter pollution in India in 2017 was 0·67 million and the number attributable to household air pollution was 0·48 million. The number of deaths due to ambient particulate matter pollution in Pakistan in 2017 was 60,000.

Climate change over 3,000 years ago destroyed the Indus Valley Civilisation and it went into oblivion, leaving behind traces of what befell the people here before. The next few decades are extremely critical. Can we summon some good sense to survive or go the way of the Meluhans? The verses of Allama Iqbal, albeit in another context, still hold true: Watan ki fiqr kar nadaan museebat aane wali hai/ Teri barbadiyon ke mashware hain aasmanon mein…/ Na samjhoge tou mit jaoge Hindustan walon/ Tumari daastan tak bhi na hoge daastanon mein. (Think of the homeland, O ignorant one! Hard times are coming./Conspiracies for your destruction are afoot in the heavens./You will be finished if you do not care to understand, O ye people of India!/Even the mention of your being will disappear from the world’s chronicles).

The author is a prolific commentator on economic, security, and China issues. He is a Trustee/Governing Council member of TPF.

This article was published earlier in Deccan Chronicle.

Image source: www.pri.org