The war, which began when NATO leaders dismissed Russia’s demand for security guarantees from the West, was intended as a way for Russia to reclaim its power and prestige on the global stage while strengthening its security in the region. Neither of these objectives has been achieved, nor will they be with Ukraine’s defeat. The war quickly escalated into a proxy conflict between Moscow and the collective West, with significant losses on both sides.

Given that President Putin has recently signed an order to draft 160,000 additional soldiers with the goal of “finishing off” the Ukrainian resistance, the Russia-Ukraine war is far from a definitive resolution. Nonetheless, it is never too early to begin considering the options for a successful post-war settlement and the potential to transform the US-advocated ceasefire (if it ever materializes) into a lasting peace.

Unfortunately, neither side of the conflict has presented anything even remotely resembling a plan for a sustainable, acceptable post-war settlement. The war, which began when NATO leaders dismissed Russia’s demand for security guarantees from the West, was intended as a way for Russia to reclaim its power and prestige on the global stage while strengthening its security in the region. Neither of these objectives has been achieved, nor will they be with Ukraine’s defeat. The war quickly escalated into a proxy conflict between Moscow and the collective West, with significant losses on both sides. Russia’s international security situation is now worse than it was before the war began, and this will remain the case for some time, regardless of what happens in Ukraine.

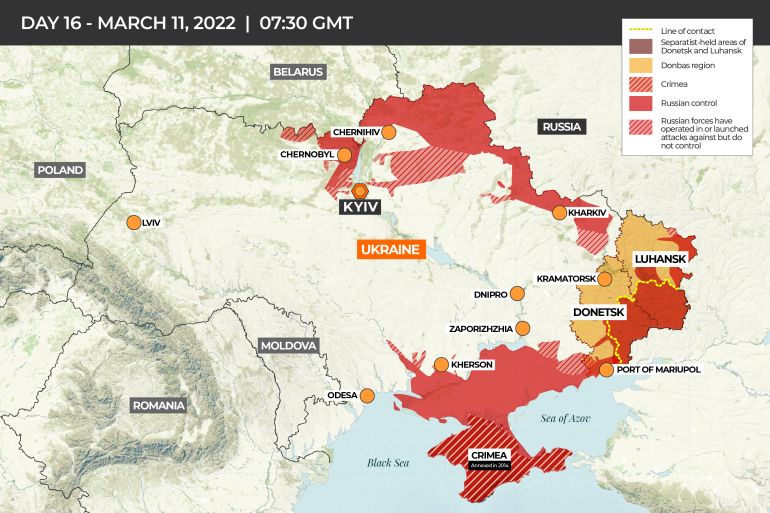

Ukraine, in fact, is fighting a losing battle. Its leaders are sacrificing the country in the midst of a geopolitical rivalry involving Russia, Europe, and the USA. If Ukraine accepts a Trump-mediated deal with Russia, it will lose four regions occupied by Russian forces since 2022, agree to the annexation of Crimea, and abandon any hopes of NATO membership in the future. If Ukraine is defeated on the battlefield, it will lose its independence and be forced to submit to what Russian leaders refer to as demilitarization and denazification—essentially, a regime change and the reconstitution of Ukrainian governance.

With no realistic prospect of pushing Russian forces out of the country and with the increasing likelihood of an exploitative “resources plus infrastructure” deal imposed by Washington, Ukraine risks losing not only its state sovereignty but any semblance of international agency. If Ukraine’s role in a post-war settlement, as envisioned in the Saudi negotiations, is reduced to either a Russian-occupied territory or a de facto resource colony of the United States, such a “settlement” would merely serve as an interlude between two wars, offering no lasting resolution to the conflict.

As the Kremlin proposes placing Ukraine under external governance and the White House demands control over all of Ukraine’s natural resource income for several years—along with a perpetual share of that revenue—the process of transforming Ukraine into a non-self-governing territory accelerates. However, Russia also faces setbacks. Despite Putin’s efforts to halt NATO’s expansion and push the alliance back to its 1997 military posture, NATO has grown closer to Russia’s borders, with formerly neutral Sweden and Finland joining the alliance in direct response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Trump’s previous alignment with Putin prompted EU leaders to agree to a substantial €800 billion increase in defence spending, while French President Macron proposed extending France’s nuclear deterrent to protect all of Europe from potential Russian threats. This may lead to France positioning its nuclear-capable jets in Poland or Estonia, and its ballistic-missile submarines in the Baltic Sea. The British nuclear deterrent is already committed to NATO policy, and it is not unimaginable that some or all of the UK’s nuclear submarines could be deployed closer to Russia’s borders. A UK contribution to a European nuclear umbrella, along with the creation of a low-yield variant of existing nuclear capabilities, would further erode Russia’s already fragile security.

Putin’s proposal for the external governance of Ukraine reveals Russia’s deep vulnerabilities, which the full occupation of Ukraine would soon expose. A collapse of Ukrainian statehood and the need to occupy the entire country would require Russia to maintain an occupation force of several hundred thousand troops, while also assuming responsibility for law enforcement, security, state administration, essential services, and more. Rebuilding Ukraine’s devastated southeast would cost billions of dollars, and efforts to restore the entire former Ukrainian nation are simply beyond Russia’s capacity. Meanwhile, the guerrilla warfare that the Ukrainians will inevitably intensify in response to Russia’s territorial expansion will further drain the occupiers’ resources.

The end of the war would mark a slowdown in the military-industrial complex that has driven Russia’s economic growth in recent years. Additionally, the ongoing militarization of society, the rise of nationalist totalitarianism, and the enormous costs of occupying the “new territories” highlight the Pyrrhic nature of Russia’s supposed “victory.”

Despite the Kremlin’s bravado, Russia’s economy and society have been significantly weakened by the war. With the key interest rate at 21 percent, annual inflation at 10 percent, dwindling welfare fund reserves, and an estimated 0.5 to 0.8 million casualties (killed and wounded) on the battlefield, it’s unclear how much longer Putin can stave off economic decline and maintain reluctant public support for his administration. The end of the war would mark a slowdown in the military-industrial complex that has driven Russia’s economic growth in recent years. Additionally, the ongoing militarization of society, the rise of nationalist totalitarianism, and the enormous costs of occupying the “new territories” highlight the Pyrrhic nature of Russia’s supposed “victory.” The best possible settlement from Russia’s perspective—leaving a rump Ukraine that is independent, self-sufficient, and friendly—is simply out of reach. The remaining options will only delay the inevitable second round of hostilities.

Finally, the Western proposals for post-war settlements are either unsustainable or outright counterproductive. This is perplexing, given that the war has cost Europe dearly, and it should be in the EU’s interest to see it end as soon as possible. While predictions of seeing the Russian economy in tatters have not materialized, Europe now faces an imminent financial crisis. With the EU economy growing by less than 1 percent in 2024, while Russia’s economy grows 4.5 times faster, it’s time for those like President Macron of France—who advocate continuing the war with extensive European military and financial support—to reconsider their stance.

However, this is not happening. Instead, EU leaders are urging Russia to agree to an “immediate and unconditional ceasefire on equal terms, with full implementation,” under the threat of new sanctions and the redoubling of Europe’s support for Ukraine.

This approach is counterproductive and likely to strengthen Russia’s resolve. Beyond the fact that continued support for Ukraine’s war effort will further strain the already fragile budgets of the supporting states, insisting that Ukraine fight to the bitter end is both practically and morally indefensible. At the same time, abandoning Ukraine to face Russia alone could lead to the collapse of Ukrainian statehood. In either case, the collective West loses.

A negotiated settlement, as proposed by President Trump, is a lesser evil under the current circumstances. Yes, it’s a suboptimal solution that could embolden Putin, harm Ukraine, deepen the divide between Russia and Europe, and create new challenges for international security.

Yet, the preservation of Ukrainian statehood would be ensured. Death and destruction would cease. Europe’s economy would recover, and the global economy would see a boost. The risk of nuclear war in Europe would fade away. The need for European citizens to stockpile 72 hours’ worth of supplies, as per the European Commission’s recent guidance, might become less of a priority for the already-intimidated European citizens.

European leaders should consider working alongside Trump, Putin, and Zelensky to craft a balanced, negotiated solution that accounts for the interests of all sides. Even if everyone must make sacrifices, it is better than losing everything.

While any path out of this war will be difficult, the strategy of threatening Russia with harsher sanctions, forming “coalitions of the willing,” and creating EU nuclear-armed forces will not make it any easier. Instead, European leaders should consider working alongside Trump, Putin, and Zelensky to craft a balanced, negotiated solution that accounts for the interests of all sides. Even if everyone must make sacrifices, it is better than losing everything.

Feature Image Credit: www.pbs.org