Title : Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy

Winner of the 2018 Leontief prize for advancing the frontiers of economic thought ─ “Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy” by Mariana Mazzucato is an extremely important addition to the contemporary debates in development economics. Fundamental ideas presented in the book are very relevant in the current pandemic environment as it gives us an opportunity to reframe approach to policy making. Limitations in the state’s capacity to handle a crisis of this scale might be true but the larger objective to ensure an economic and social value based ecosystem is the main idea that emerges from this book.

The core focus of the book is on the ‘understanding of value’, as Mariana states – “much of what is passing for value creation is just value extraction in disguise”. By examining what is value the book leads us to understanding who creates value.

Initial chapters set out to explain the core interpretation of ‘value’ adopting a historical framework by discussing influential economists. Beginning with Mercantilists in an inchoate system that was not linked with any theories to explain the creation of wealth, they believed trade creates wealth and hence, ‘value’ lies within trade. A group of 18th century French economists developed a formal economic theory ‘physiocracy’ that prioritized agriculture and land to be the ultimate source of value. There was a clear production boundary that was developed during the time of physiocrats with agriculture being productive and household, government, service, industry packed together as unproductive. Countering the Mercantilists, Adam Smith theories became prominent to understand the idea of value where wealth creation lies in an optimal economic policy encouraging surplus revenue to be reinvested in production for the nation to become richer. The author points to the theories put forth by Smith to be ambiguous yet made progress in building the concept of wealth creation. David Ricardo– a British political economist extensively wrote about rent and assumed land to be a fixed factor. As opposed to Physiocrats, Ricardo’s theory on value was beyond the production boundary and placed emphasis on financing the surplus into productive spending. The author briefly evaluates the classical theories including Marx’s labour value theory and the recent development of Marginalists under the neoclassical economics. It is worth contesting the idea of value in the marginalist approach where the price is equated to value and individual utility is studied over collective public utility . Although the theories in principle might not be relevant today but the evolution of value in the history of economic thought is a prerequisite to identify the flaws in our structure.

A key focal point that grabs attention of the reader is the ambiguity present in determining the value of products and services. Reluctance to debate the idea of value with the current system has caused trouble in various sectors and the book reflects Mazzucato’s effort to place value in the centre-stage. She begins to make her case by lucidly explaining the fundamental shortcomings in finance deregulation. In the context of the 2008 financial crisis, much of the blame is on the finance market with excessive mortgaging strategy. Although finance is not a categorical reason for the crisis, the real estate bubble was artificially inflated by the short term objectives of finance companies and clearly proved to be unsuccessful. There are two relevant points that the author notes that will hold relevance across the waves of industrialization. First, economic value added by a finance sector largely remains disproportionate to the value added by other sectors. As a resource facilitator, she asserts, banking corporations are required to invest in productive business that adds further economic value in the society. Mere exchange of financial instruments does not guarantee increased output or welfare in an economy. It has taken a crisis for us to understand the need for steering the discussion on ‘Value Creation’. Second, financial markets bolstering private businesses model prioritizes immediate gains with limited attention paid to the long-run sustainability of the business.

The book is a scathing indictment of the current global financial system. In the authors view the finance entrepreneurs are overrated, and contrary to popular perception they are not ‘value creaters’ but are ruthless ‘value extractors’ and parasitic. Professor Mazzucato finds the shareholder driven model to be problematic for business innovation and proposes a wider concept of stakeholder based operations. An unequivocal argument is presented to question ‘value extraction’ in the 21 century economy- in public choice theory it would mean rent seeking, a concept of increasing existing share of one’s wealth without creating more wealth. Although the author did not specifically mention the Asian countries, in Indian context, value extraction is much difficult to identify given the informality in credit market, labour market and commodities. But the unsustainable mode of executing business is evident in a corporate company that is motivated to spend on company image than Research and Development. Most importantly, the government bears the cost to repair the system with social tension and inequality that follows the failure of excess financialization. The author’s discussion on development and welfare throughout the chapters encourages readers to view the economy beyond numbers and growth rate– a propensity stemming from modern heterodox economics school of thought

Mariana Mazucatto, founder of the Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose, draws attention to value extraction prevailing in the innovation economy. She illustrates three sources of innovation; cumulative innovation, uncertain innovation and collective innovation. She clearly articulates the engaging role of the public sector in facilitating innovation. Where most experts talk about innovation as an exclusive achievement of the private sector– Mariana challenges that notion and argues the risks of the innovation are borne by the public but the rewards are monopolized by the private business. It is impossible to deny the role of public sector in the process of innovation but it seems the author tends to credit the government more. All innovation need not create value- an extensive literature is presented to understand the way patents can be used to gain economically yet not create value. Highlighting the case of pharmaceuticals, she argues that most of the drug companies are monopolies that use the patent strategy and the rigid demand to inflate the prices for enormous profit although the production cost is a small percentage of the price. This process explains the high priced medicines in the USA and rekindles the fundamental flaw in pricing of a drug. An extreme private model with little clarity and transparency on value of the service has collapsed the healthcare system in the US, which is starkly evident in the current COVID-19 pandemic. To extend this idea, American healthcare contributes more to the Gross Domestic Product compared to the Japanese, yet citizens of the latter have higher life expectancy than of the former. The illusion of GDP contribution is more apparent when the system fails to serve the purpose it was designed for, like in the case of healthcare. Innovations in any industry can turn out to be unproductive; dismissing any single command approach from the government– the chapter ends by propounding a contract between public and private to adopt innovation as a means to achieve public value.

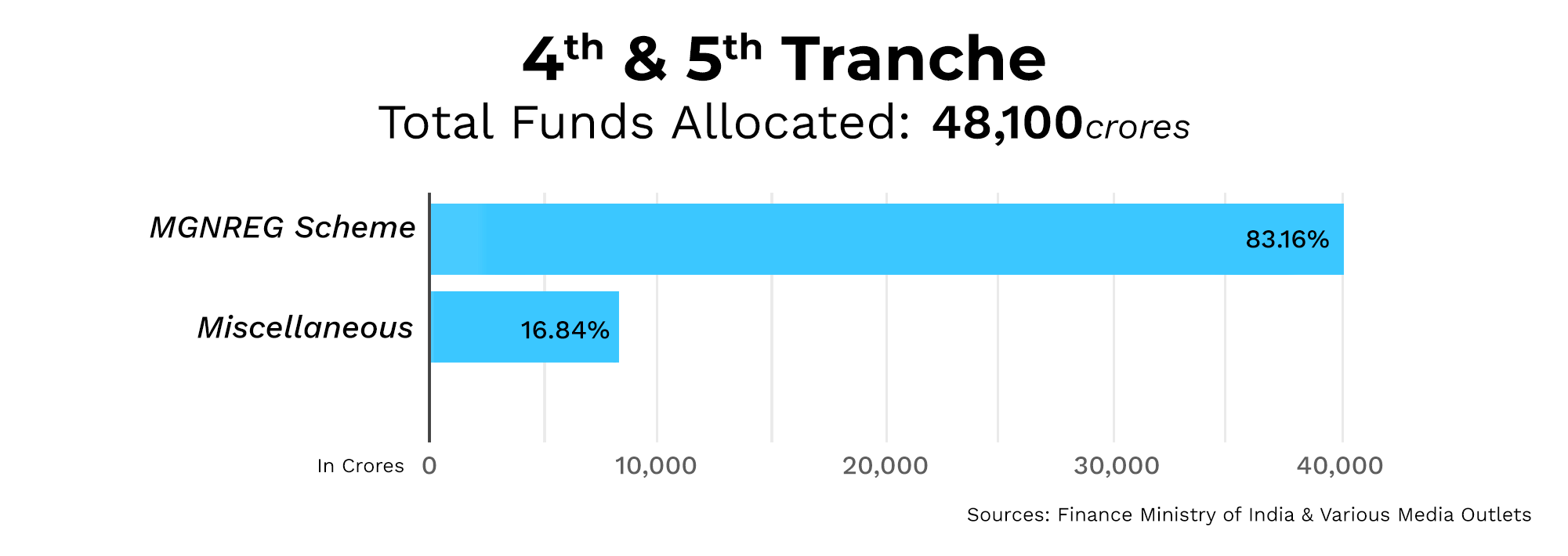

In contemporary discourse, the author is concerned about the narrow definition of public sector as simply a saviour or a disturbance to private operations. A powerful narrative set to describe government to be inefficient and just an institution fixing market failure will deter the collective process of value creation. The recent economic stimulus announced by India is founded on the logic that public debt is bad, slashing interest rates would enhance business and privatization would lead to better economic growth. As Mazucatto argues, during an economic crisis public sector must seize the opportunity to invest in value creation simply because interest rates are neither market phenomena nor make firms sensitive to the change. The underrated value of the Keynesian ‘Multiplier Effect’ of public investment and considering the return on public investment to be zero are flaws in defining the role of government in contributing to growth of the economy.

Prevailing public choice theorists’ fear of government failure over and above the threat posed by market failure runs the risk of ignoring the value created by the state. The author makes a compelling case to view government as an investor rather than spender and as a risk taker rather than a facilitator. She highlights the importance of the state’s part in the collective value creation process by disputing the marginalists definition of individual value in obtaining market value. Knitting back to the initial problem stated regarding price equal to value– identifying profit and rent becomes confusing thereby encouraging private players to extract or destroy value. The mainstream metrics used to assess the value also discourages actual value creators like the government to imitate the private sector. The government as a facilitator also faces the risk of lobbying from the private individuals and companies that hamper the process of development. The last chapter – ‘Economics of Hope’– summarizes the main ideas presented throughout the book and emphasises that the ultimate goal of the economy is to serve the people and ensure welfare along with sustainable and equitable development. The real challenge still lies in estimating the precise amount of government intervention in the process of value creation. Value of everything remains a convincing genesis of the debate on the central idea of value that could possibly be a dynamic tool to achieve the goals of an economic system.

As Mariana Mazucato argues in this penetrating and passionate book, if we are to reform capitalism to radically transforman increasingly sick system rather than continue feeding it we urgently need to rethink where wealth comes from; who is creating it, who is extracting it, and who is destroying it. Answers to these questions are key if we want to replace the current parasitic system with atype of capitalism that is more sustainable, more symbiotic, that works for all.