In anticipation of a holiday gift, I kept asking members of my research team every week whether they noticed any anomalous object among the nearly hundred thousand objects imaged by the Galileo Project Observatory at Harvard University over the past couple of months. The reason is simple.

Finding a package from a neighbour among familiar rocks in our backyard is an exciting event. So is the discovery of a technological object near Earth that was sent from an exoplanet. It raises the question: which exoplanet? As a follow-up on such a finding, we could search for signals coming from any potential senders, starting from the nearest houses on our cosmic street.

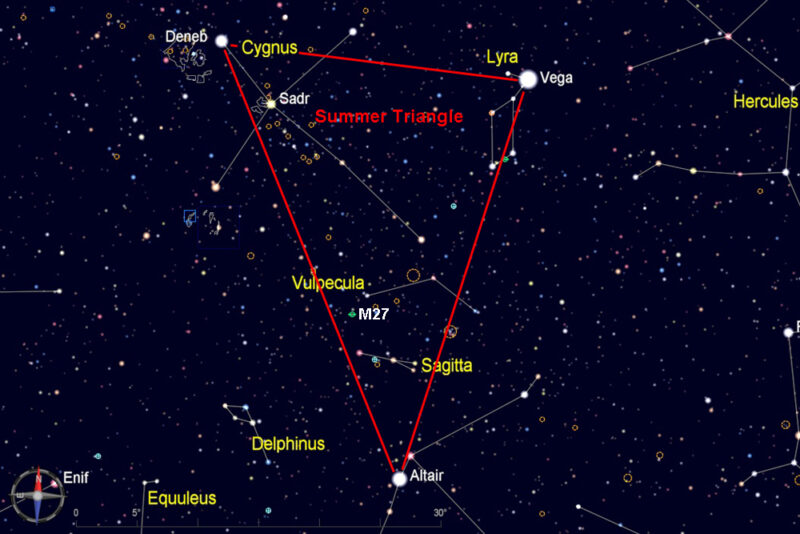

Summer Triangle, which consists of the three of the brightest stars in the sky–Vega, Deneb, and Altair. The Summer Triangle is high overhead throughout the summer, and it sinks lower in the west as fall progresses. For this star hop, start from brilliant blue-white Vega (magnitude 0), the brightest of the three stars of the Summer Triangle.

Summer Triangle, which consists of the three of the brightest stars in the sky–Vega, Deneb, and Altair. The Summer Triangle is high overhead throughout the summer, and it sinks lower in the west as fall progresses. For this star hop, start from brilliant blue-white Vega (magnitude 0), the brightest of the three stars of the Summer Triangle.

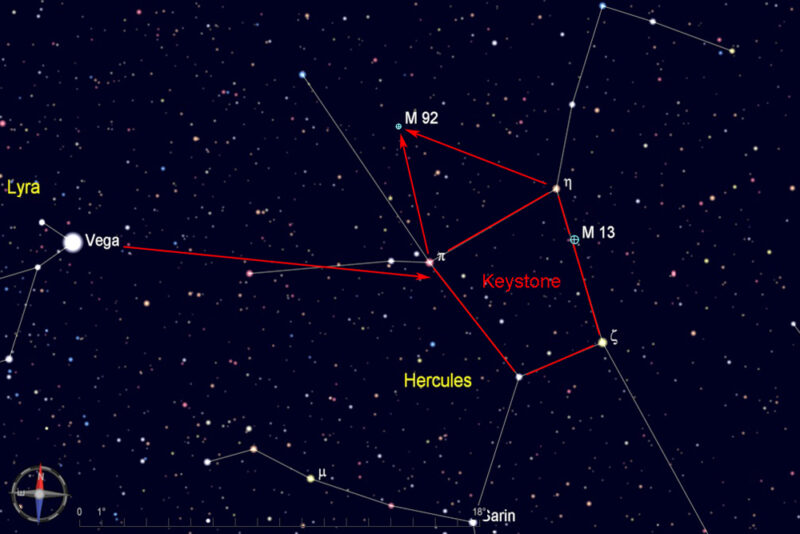

From Vega, look about 15 degrees west for the distinctive 4-sided figure in the centre of Hercules known as the keystone. On the north side of the keystone, imagine a triangle pointing to the north, with the tip of the triangle slightly shifted toward Vega (as shown in the chart below). This is the location of M92.

From Vega, look about 15 degrees west for the distinctive 4-sided figure in the centre of Hercules known as the keystone. On the north side of the keystone, imagine a triangle pointing to the north, with the tip of the triangle slightly shifted toward Vega (as shown in the chart below). This is the location of M92.

The opportunity for a two-way communication with another civilization during our lifetime is limited to a distance of about thirty light years. How many exoplanets reside in the habitable zone of their host star? This zone corresponds to a separation where liquid water could exist on the surface of an Earth-mass rock with an atmosphere. Also known as the Goldilocks’ zone, this is the separation where the temperature is just right, not too cold for liquid water to solidify into ice, and not too hot for liquid water to vaporize.

So far, we know of a dozen habitable exoplanets within thirty light years (abbreviated hereafter as `ly’) from Earth. The nearest among them is Proxima Centauri b, at a distance of 4.25 ly. Farther away are Ross 128b at 11 ly; GJ 1061c and d at 11.98 ly, Luyten’s Star b at 12.25 ly, Teegarden’s Star b and c at 12.5 ly, Wolf 1061c at 14 ly, GJ 1002b and c at 15.8 ly, Gliese 229Ac at 18.8 ly, and planet c of Gliese 667 C at 23.6 ly. These confirmed planets have an orbital period that ranges between a week to a month, much shorter than a year because their star is fainter than the Sun. This list must be incomplete because two-thirds of the count is within a distance of 15 ly whereas the volume out to 30 ly is 8 times bigger. Given that the nearest habitable Earth-mass exoplanet is at 4.25 ly, there should be of order four hundred similar planets within 30 ly. We are only aware of a few per cent of them.

But even if we identified all the nearby candidate planets for a two-way conversation, they would constitute a tiny fraction of the tens of billions of habitable planets within the Milky Way galaxy. Having any of the nearby candidates host a communicating civilization would imply statistically an unreasonably large population of transmitting civilizations for SETI surveys.

Most likely, any visiting probe we encounter had originated tens of thousands of light-years away. In that case, we will not be able to converse with the senders during our lifetime. Instead, we will need to infer their qualities from their probes, similarly to the prisoners in Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, who attempt to infer the nature of objects behind them based on the shadows they cast on the cave walls.

It is better not to imagine your neighbours before meeting them because they might be very different than anticipated. My colleague Ed Turner from Princeton University, used to say that the more time he spends in Japan, the less he understands the Japanese culture. According to Ed, visiting Japan is the closest he ever got to meeting extraterrestrials. My view is that an actual encounter with aliens or their products would be far stranger than anything we find on Earth.

Personally, I am inspired by the stars because they might be home to neighbours from whom we can learn. The stars in the sky look like festive lights on a Christmas tree which lasts billions of years. A few days ago, a woman coordinated dinner with me as a holiday gift to her husband, who follows my work. At the end of dinner, they gave me a large collection of exceptional Japanese chocolates, which I will explore soon. In return, I autographed my two recent books on extraterrestrials for their kids with the hope that they would inherit my fascination with the stars.

Here’s hoping that our children will have the opportunity to correspond with the senders of an anomalous object near Earth. During this holiday season, I wish for a Messianic age of peace and prosperity for all earthlings as a result of the encounter with this gift.

Feature Image Credit: Messier 92 is one of two beautiful globular clusters in Hercules, the other being the famous M13. Although M92 is not quite as large and bright as M13, it is still an excellent sight in a medium to large telescope, and it should not be overlooked. The cluster is about 27,000 light years away and contains several hundred thousand stars. www.skyledge.net

Other Two Pictures in Text: www.skyledge.net

This article was published earlier in medium.com