Utilisation of the country’s resources needs to be decided jointly by the Centre and the States. The changed political situation after the general election makes this feasible.

The results of the general election 2024 have thrown up a surprise. They portend greater democratisation in the country, with the regional parties doing well. These parties will share space on the ruling party benches as well as on the Opposition side in Parliament. This will help strengthen federalism, which is so crucial for a diverse nation such as India. It was badly fraying until recently.

Centre-State relations became contentious during the general election campaign. The idea of’ 400 par’, ‘one nation, one election’, and the Prime Minister threatening that the corrupt (i.e., Opposition leaders) would soon be in jail were perceived as threats to the Opposition-ruled States.

The Opposition-ruled States have been complaining about step-motherly treatment by the Centre. Protests have been held in Delhi and the State capitals. The Supreme Court of India has said that ‘a steady stream of States are compelled to approach it against the Centre’. Kerala has complained about the inadequate transfer of resources, Karnataka about drought relief and West Bengal about funds for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS). The attempt seems to be to show the Opposition-ruled States in a bad light.

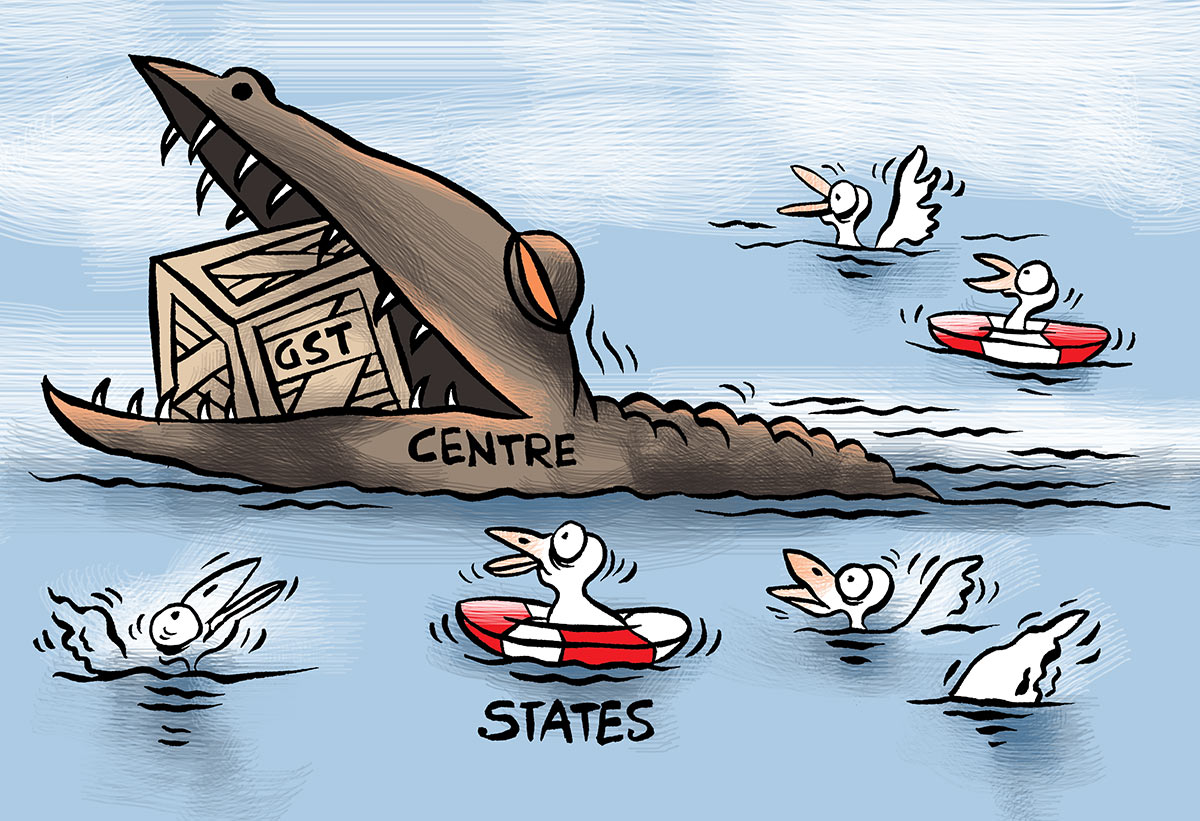

The Supreme Court, expressing its helplessness, recently said that Centre-State issues need to be sorted out amicably. When the Bharatiya Janata Party came to power in 2014, it had talked of cooperative federalism. The introduction of the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in 2017 was an example of this when some States that had reservations about it eventually agreed to its rollout. But that was the last of it. With federalism fraying, discord has grown between the Centre and the Opposition-ruled States.

There is huge diversity among the States—Assam is unlike Gujarat, and Himachal Pradesh is very different from Tamil Nadu. A common approach is not conducive to the progress of such diverse States. They need greater autonomy to address their issues in their own unique ways. This is both democracy and federalism. So, a dominant Centre forcing its will on the States, leading to the deterioration in Centre-State relations, does not augur well for India.

Financing and conflict is one issue

States face three broad kinds of issues. Some of them can be dealt with by each State without impacting other States, such as education, health, and social services. But infrastructure and water sharing require States to come to an agreement. Issues such as currency and defence require a common approach. The last two kinds of issues require a higher authority, in the form of the Centre, to bring about coordination and optimality.

Expenditures have to be financed to achieve goals, and that results in conflict. Revenue has to be raised through taxes, non-tax sources and borrowings. The Centre has been given a predominant role in raising resources due to its efficiency in collecting taxes centrally. Among the major taxes, personal income tax (PIT), corporation tax, customs duty and excise duty are collected by the Centre. GST is collected by both the Centre and the States and shared. So, the Centre controls most of the resources, and they have to be devolved to the States to enable them to fulfil their responsibilities.

The Centre sets up the Commission and has mostly set its terms of reference. This introduces a bias in favour of the Centre and becomes a source of conflict between the Centre and the States.

A Finance Commission is appointed to decide on the devolution of funds from the Centre to the States and the share of each State. The Centre sets up the Commission and has mostly set its terms of reference. This introduces a bias in favour of the Centre and becomes a source of conflict between the Centre and the States. Further, there has been an implicit bias in the Commissions that the States are not fiscally responsible. This reflects the Centre’s bias — that the States are not doing what they should and that they make undue demands on the Centre.

The States also pitch their demands high to try and get a larger share of the revenues. They tend to show lower revenue collection and higher expenditures in the hope that there will be a greater allocation from the Commission. The Commission becomes an arbiter, and the States the supplicants.

Inter-State tussles, Centre-State relations

The States cannot have a common position as they are at different stages of development and with vastly different resource positions. The rich States have more resources, while the poor ones need more resources in order to develop faster and also play catch up. So, the Finance Commission is supposed to devolve proportionately more funds to the poorer States. Unfortunately, despite the efforts of the 15 Finance Commissions so far, the gap still remains wide.

The rich States, which contribute more and get proportionately less, have resented this. What they forget is that the poorer States provide them the market, which enables them to grow faster. The poorer States also lose much of their savings which leak out to the rich States, accelerating their development. It is often said that as Mumbai contributes a bulk of the corporate and income taxes, it should get more. But this is because Mumbai is the financial capital. So, the big corporations are based there and pay their tax in Mumbai. More revenue is contributed in an accounting sense, and not that production is taking place in Mumbai.

The Centre allocates resources to the States in two ways. First, on account of the Finance Commission award. Second, the Centre is notional, while the States are real. So, all expenditures by the Centre are in some State. The amount spent in each State is also a transfer. This becomes another source of conflict. Expenditures lead to jobs and prosperity in a State. Benefits accrue in proportion to the funds spent. As a result, each State wants more expenditure in its territory. The Centre can play politics in the allocation of schemes and projects. For instance, it is accused of favouring Gujarat and Uttar Pradesh. The Opposition-ruled States have for long complained of step-motherly treatment.

To get more resources, the States have to fall in line with the Centre’s diktat. This has taken a new form when the call is for a ‘double engine ki sarkar’, i.e. for the same political party to be governing at the Centre and the States. It is an admission that the Opposition-ruled States will be at a disadvantage. This undermines the autonomy of the States and also weakens federalism.

State autonomy is not to be confused with freedom to do anything. It is circumscribed by the need to function within a national framework for the wider good. It implies a fine balance between the common and the diverse.

Issues in federalism

The Sixteenth Finance Commission has begun work. It should try to reverse fraying federalism and strengthen the spirit of India as a ‘Union of States’. This is not only a political task but also an economic one. The Commission could suggest that there is even-handed treatment of all the States by the Centre and also less friction among the rich and poor States when proportionately more resources are transferred to poor States so as to keep rising inequality in check.

The issue of governance, both at the Centre and in the States, needs to be flagged. It determines investment productivity and the pace of development. Corruption and cronyism lead to resources being wasted and a loss of social welfare.

To reduce the domination of the Centre over the States, the devolution of resources from the Centre to the States could be raised substantially from its current level of 41%. The Centre’s role could be curtailed. For instance, the Public Distribution System and MGNREG Scheme are joint schemes, but the Centre asserts that it be given credit. It has penalised States that have not done so.

The Centre is notional and constitutionally created, while States and local bodies are the real entities where economic activity occurs and resources are generated.

The Centre’s undue assertiveness undermines federalism. Funds with the Centre are public funds collected from the States and spent in the States. The Centre is notional and constitutionally created, while States and local bodies are the real entities where economic activity occurs and resources are generated. The States have agreed to the Centre’s constitutional position, but that does not make them supplicants for their own funds.

It is time that the utilisation of the country’s resources is jointly decided by the Centre and the States on the basis of being equal partners. This has become more feasible with the changed political situation after the results of the 2024 general election.

This article was published earlier in The Hindu.

Feature Image Credit: rediff.com