To follow the Silk Road is to follow a ghost. It flows through the heart of Asia, but it has officially vanished leaving behind the pattern of its restlessness: counterfeit borders, unmapped peoples. The road forks and wanders wherever you are. It is not a single way, but many: a web of choices.

Colin Thubron, Shadow of the Silk Road.

Introduction

India and China, two Asian giants, share a lot of similarities in terms of history and culture. Both countries represent age old civilizations and unique history. Cultural and economic ties between the two countries date back to about 2000 years ago. The Silk Route, which is an ancient network of trade routes, formally established by the Han Dynasty, served as a connection between the two countries. It was also through this route that Buddhism spread to China and East Asia from India. The routes were more than just trade routes; it was the carrier of ideas, innovations, inventions, discoveries, myths and many more.

The earliest mention of China can be found in the Indian text “Arthashastra” which was written by Kautilya in the fourth century BC. Kautilya made a remark about Cinapattasca Cinabhumjia (Cinapatta is a product of China)[1]. Whereas, the earliest mention of India in Chinese records dates between 130 and 125 BC. Zhang Qian, a Chinese envoy to Central Asia, referred to India as Shendu, in his report about India to Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty.

This article will look into the ancient trade route that existed between South Western China and India’s North East region via Myanmar and the future of the trade route.

Ancient trade links between India and China

Shiji, which is the first Chinese dynastic history, compiled between 104 and 87 BCE talks about the existence of a trading route between India and South West China. According to Chinese records, Emperor Wu of the Han dynasty, tried to establish a trade route from Changan, the Chinese capital to North East India through Yunnan and adjoining areas. However, the rulers of Yunnan were against the idea of establishing a direct trade between India and China and Emperor Wu failed to establish the trade route. Even though the trade route failed to take off, the trade in Cinapatta and Chinese square bamboo continued without any hindrance.

Political Geography of the Southern Silk Route

The Southern Silk route (SSR), one of the least studied overland route, is a trade route which is about 2000 km long and linked East and North East India with Yunnan Province of China via Myanmar. This is a relatively unknown, ancient trade route that is considered a part of the larger web of Silk Roads. This route existed before the Central Asian Silk route became popular. This trade route between Eastern India and China came to be known during the early 3rd century BCE, and it became popular by the 2nd century BCE. By 7th century AD various other branches of the SSR emerged to create web of trading routes.

Traders carried silk from Yunnan through Myanmar, across India and joined the main silk route in Afghanistan. In addition, silk was also transported from South West China through the Shan states and North Myanmar into East India and then down to the Coromandel Coast.

The Qing dynasty which ruled China from 1644-1912, recorded the cross cultural exchanges that took place across SSR. This route contributed to cultural exchanges between China and the West. It also promoted interactions among different nationalities.

Indian sources have failed to provide abundant evidence about the SSR and the interaction that took place across this route but there is enough evidence that indicates that trade and migration did take place in the Eastern India-Upper Myanmar-Yunnan region. For example, modern scholars believed that the Tai Ahoms were originally from Yunnan but they migrated to North East India and founded a small kingdom around 13th century, which grew to become the powerful Ahom Kingdom of Assam.

The areas through which the SSR passed were inhabited by various ethnic groups whose political, social and economic organizations were primitive and backward. As a result, the safety of the route was often questioned. Archeological evidences have been found along the Southern banks of Brahmaputra up to Myanmar border, which shows that trade did exist along this route.

The main items that were exported from China via this route included Silk, Sichuan cloth, Bamboo walking sticks, ironware and other handicrafts items. Sichuan, a South Western province was the main source of silk. Glass beads, jewels, emeralds etc were some of the items that were imported to China.

Another important trade route is the South West Silk route or the Sikkim Silk route, which connected Yunnan, and India through Tibet. A section of the route from Lhasa crossing Chumbi Valley, Nathu La Pass connected to the Tamralipta Port (present day Tamluk in West Bengal). From the Tamralipta port, this trade route took to the sea to traverse to Sri Lanka, Bali, Java and other parts of the Far East. Another section of the route crossed Myanmar and entered India through Kamrup (Assam) and connected the ports of Bengal and present day Bangladesh.

Over time, the Southern Silk Route lost its prominence and it was in 1885 that it re- emerged as a strategic link as the British tried to control some parts of the route in order to access and gain control over Southern China.

The strategic importance of the route increased during World War II. In 1945, Ledo Road or Stilwell Road was constructed from Ledo, Assam to Kunming, Yunnan to supply aid and troops to China for the war with Japan. Ledo Road is the shortest land route between North East India and South West China. However, after the war the road was left unused and in 2010, BBC reported that much of the Ledo road has been swallowed up by jungle.

The Assam-Myanmar-Yunnan road is very difficult to traverse not only in the present times but also during the ancient times. However, despite the hard conditions, it is through this route that a golden triangle of drug trafficking, movement of terrorist and smuggling functions today.

Future Potential: Reviving the Southern Silk Route Economy

North-East India and the Yunnan province share many similarities. Both are landlocked as well as under developed regions. Both are home to a large number of ethnic groups and have witnessed secessionist movement from time to time. Apart from this, Yunnan and North East India are geographically isolated from their political capitals.

Yunnan and North East India, home to rich varieties of subtropical fruits with high nutritional values and medicinal plants, can cooperate and transform the hills of North East India and South West China into plantations, factories, laboratories to produce processed food products and lifesaving drugs that can find a huge market in developing and developed countries.

In a bid to revive the Southern Silk route, Bangladesh, China, India and Myanmar, signed the Kunming Initiative, a sub-regional organization, in 1999. This initiative was replaced by the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM-EC) in 2015. The BCIM-EC was announced by China as a part of its Belt-Road Initiative, which has been boycotted by India since the beginning. In 2019, the BCIM-EC was dropped from the list of 35 projects that are to be undertaken under BRI, indicating that China has disreagrded the project. However, in the same year India has sought to keep the BCIM-EC project alive.

If the BCIM-EC project does take place, it will reduce the travel time, cut transportation cost, open up markets, provide way for joint exploration and development of natural resources and create production bases along the way. Before the BCIM-EC takes off, it is important to develop the roadways infrastructure of India’s North East region.

Even though the BCIM-EC promises to elevate the economic conditions of the backward North-East region of India, it has not gained sufficient steam as both China and India have different apprehensions. China sees India’s reluctance to support BRI as the barrier for any progress in the project. Given the current stand-off in Ladakh, India’s apprehensions about China seeking to exploit the insurgent groups operating in the region gains significance. Either way realizing the Southern Silk Road as a viable project in the form of BCIM-Economic Corridor looks distant now.

[1]Haraprasad Ray, “Southern Silk Route: A Perspective,” in The Southern Silk Route : Historical Links and Contemporary Convergences (Routledge, 2019).

References

Ray, Haraprasad. “Southern Silk Route: A Perspective.” Essay. In The Southern Silk Route: Historical Links and Contemporary Convergences. Routledge, 2019.

“Continental and Maritime Silk Routes: Prospects of India- China Co-operations.” In Proceedings of the 1st ORF-ROII Symposium. Kunming, 2015.

Mukherjee, Rila. “Routes into the Present.” Essay. In Narratives, Routes and Intersections in Pre-Modern Asia, 37–40. Routledge, 2017.

UNESCO. Accessed June 20, 2020. https://en.unesco.org/silkroad/content/did-you-know-great-silk-roads.

“The Silk Route.” Accessed June 21, 2020. http://www.sikkimsilkroute.com/about-silk-route/.

Ray, Haraprasad. Introduction. In North East India’s Place in India-China Relations and Its Future Role in India’s Economy, n.d.

Chowdhury, Debasish Roy. “’Southern Silk Road’ Linking China and India Seen as Key to Boosting Ties.” South China Morning Post, October 23, 2013.

“China Wants to Revive ‘Southern Silk Road’ with India.” The Times of India, June 9, 2013.

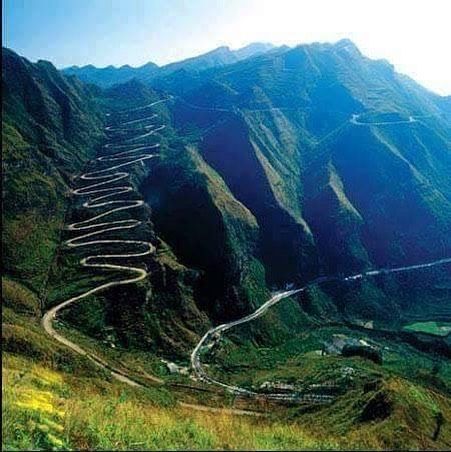

Image: Stilwel Road from Ledo in Northeast India to Kunming in Yunnan province, China