Download

[/powerkit_button]

The irrational amounts that the Soviet Union allocated to its defense budget not only represented a huge burden on its economy, but imposed a tremendous sacrifice on the standard of living of its citizens. Subsidies to the rest of the members of the Soviet bloc had to be added to this bill.

Such amounts were barely sustainable for a country that, as from the first half of the 1960s, was subjected to a continuous economic stagnation. This situation became aggravated by the strong decline of oil prices, USSR’s main export, since the mid 1980s. The reescalation of the Cold War undertaken by Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, particularly the latter, put in motion an American military buildup, that could not be matched by Moscow.

With the intention of avoiding the implosion of its system, Moscow triggered a reform process that attained none other than accelerating such outcome. Indeed, Mikhail Gorbachev opened the pressure cooker hoping to liberate, in a controlled manner, the force contained in its interior. Once liberated, however, this force swept away with everything on its path. Initially came its European satellites, subsequently Gorbachev’s power base, and, finally, the Soviet Union itself. The Soviet system had reached the point where it could not survive without changes, but neither could assimilate them. In other words, it had exhausted its survival capacity.

Without a shot being fired, Washington had won the Cold War. The exuberant sentiment of triumph therein derived translated into the “end of history” thesis. Having defeated its ideological rival, liberalism had become the final point in the ideological evolution of humanity. If anything, tough, the years that followed to the Soviet implosion were marred by trauma and conflict. In the essential, however, the idea that the world was homogenizing under the liberal credo was correct.

On the one hand, indeed, the multilateral institutions, systems of alliances and rules of the game created by the United States shortly after World War II, or in subsequent years, allowed for a global governance architecture. A rules based liberal international order imposed itself over the world. On the other hand, the so-called Washington Consensus became a market economy’s recipe of universal application. This homogenization process was helped by two additional factors. First, the seven largest economies that followed the U.S., were industrialized democracies firmly supportive of its leadership. Second, globalization in its initial stage acted as a sort of planetary transmission belt that spread the symbols, uses, and values of the leading power.

The new millennium thus arrived with an all-powerful America, whose liberal imprint was homogenizing the planet. The United States had indeed attained global hegemony, and Fukuyama’s end of history thesis seemed to reflect the emerging reality.

But things turned out to be more complex than this, and the history of the end of history proved out to be a brief one. In a few years’ time, global “Pax Americana” began to be challenged by the presence of a powerful rival that seemed to have emerged out of the blue: China. How had this happened?

Beginning the 1970s, Beijing and Washington had reached a simple but transformative agreement. Henceforward, the United States would recognize the Chinese Communist regime as China’s legitimate government. Meanwhile, China would no longer seek to constrain America’s leadership in Asia. By extension, this provided China with an economic opening to the West. Although it would be only after Deng Xiaoping’s arrival to power, that the real meaning of the latter became evident.

In spite of the multiple challenges encountered along the way, both the United States and China made a deliberate effort to remain within the road opened in 1972. Their agreement showed to be not only highly resilient, but able to evolve amid changing circumstances. The year 2008, however, became an inflexion point within their relationship. From then onwards, everything began to unravel. Why was it so?

The answer may be found in a notion familiar to the Chinese mentality, but alien to the Western one – the shi. This concept can be synthesized as an alignment of forces able to shape a new situation. More generally, it encompasses ideas such as momentum, strategic advantage, or propensity for things to happen. Which were, hence, the alignment of forces that materialized in that particular year? There were straightforward answers to that question: The U.S.’ financial excesses that produced the world’s worst financial crisis since 1929; Beijing’s sweeping efficiency in overcoming the risk of contagion from this crisis; China’s capability to maintain its economic growth, which helped preventing a major global economic downturn; and concomitantly, the highly successful Beijing Olympic games of that year, which provided the country with a tremendous self-esteem boost.

The United States, indeed, had proven not to be the colossus that the Chinese had presumed, while China itself turned out to be much stronger than assumed. This implied that the U.S. was passing its peak as a superpower, and that the curves of the Chinese ascension and the American decline, were about to cross each other. Deng Xiaoping’s advice for future leadership generations, had emphasized the need of preserving a low profile, while waiting for the attainment of a position of strength. In Chinese eyes, 2008 seemed to show that China was muscular enough to act more boldly. Moreover, with the shi in motion, momentum had to be exploited.

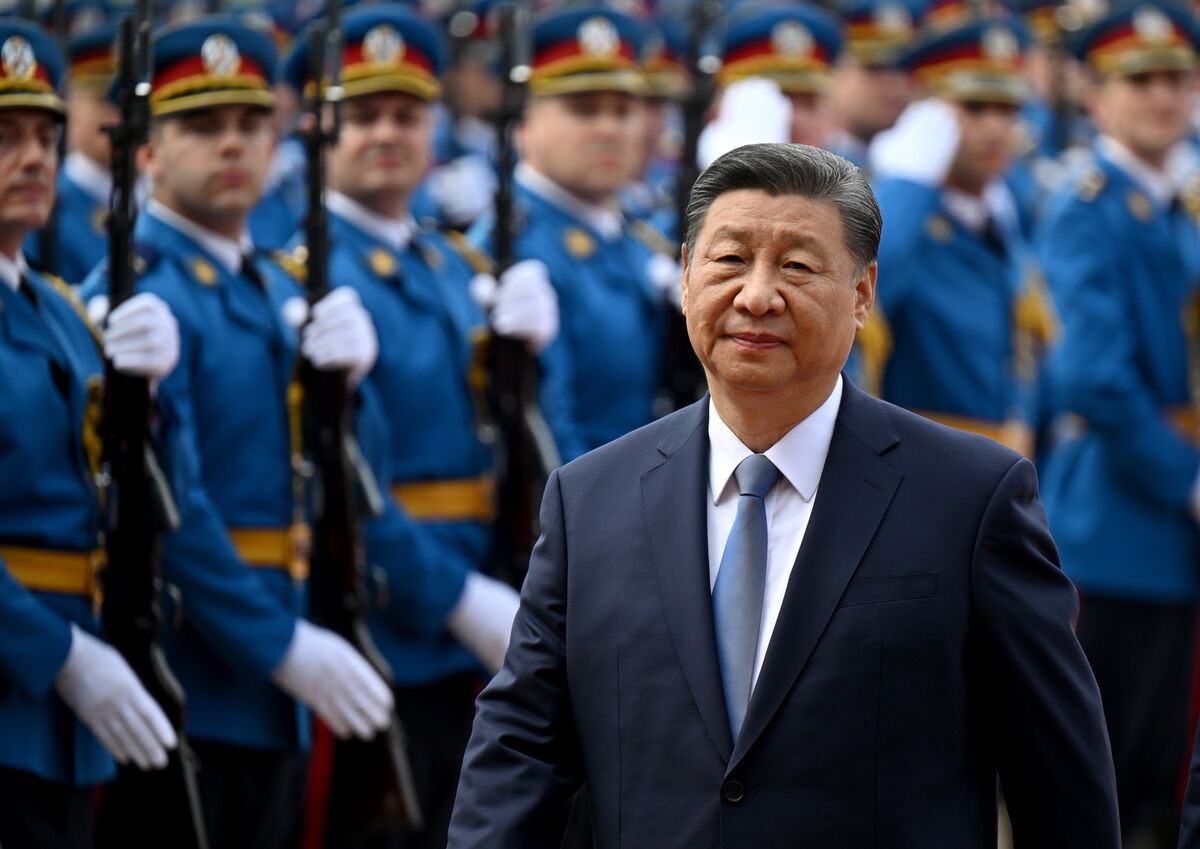

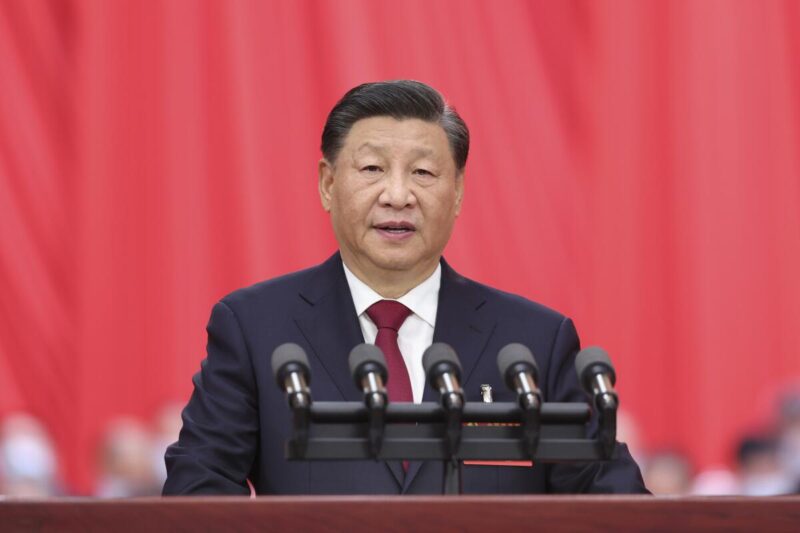

Beijing’s post-2008 assertiveness became much bolder after Xi Jinping’s arrival to power in 2012-2013. China, in his mind, was ready to contend for global leadership. More to the point within its own region, China’s centrality and the perception of the U.S. as an alien power, had to translate into pushing out America’s presence.

Challenged by China, Washington reacted forcefully. Chinese perceptions run counter to the fact that the U.S.’ had been a major power in East Asia since 1854, which translated into countless loss of American lives in four wars. Moreover, safeguarding the freedom of navigation in the South China Sea, a key principle within the rules based liberal international order, provided a strong sense of staying power. This was reinforced by the fact that America’s global leadership was also at stake, thus requiring not to yield presence in that area for reputational reasons. The containment of Beijing’s ascendancy, became thus a priority for Washington.

However, accommodating two behemoths that feel entitled to pre-eminence is a daunting task. Specially so, when one of them feels under threat of exclusion from the region, and the other feels that its emergence is being constrained. On top, both remain prisoners of their history and of their national myths. This makes them incapable of looking at the facts, without distorting them with the subjective lenses of their perceived sense of mission and superiority.

War ensuing, under those circumstances, is an ongoing risk. But if war is a possibility, Cold War is already a fact. This implies a multifaceted wrestle in which geopolitics, technology, trade, finances, alliances, and warfare capabilities are all involved. And even if important convergent interest between them still remains in place, ties are being cut by the day. As a matter of fact, if in the past economic interdependence helped to shield from geopolitical dissonances, the opposite is the case today. Indeed, a whole array of zero-sum geopolitical controversies are rapidly curtailing economic links.

The U.S., particularly during the Biden administration, chose to contain China through a regional architecture of alliances and by way of linking NATO with Indo-Pacific problems and selective regional allies. The common denominator that gathers them together is the preservation of the rules based liberal international order. An order, threatened by China’s geostrategic regional expansionism.

However, China itself is not short of allies. A revisionist axis, that aims at ending the rules based liberal international order, has taken shape. The same tries to throw back American power and to create its own spheres of influence. This axis represents a competing center of gravity, where countries dissatisfied with the prevailing international order can turn to. Together with China two additional Asia-Pacific powers, Russia and North Korea, are part of this bloc.

Trump’s return to the White House might change the prevailing regional configuration of factors. Although becoming more challenging to Beijing from a trade perspective, he could substantially weaken not only the rules based liberal international order, but the architecture of alliances that contains China. The former, because the illiberal populism that he represents is at odds with the liberal order. The latter, not only because he could take the U.S. out of NATO, but because his transactional approach to foreign policy, which favors trade and money over geopolitics, could turn alliances upside down.

The rules based liberal international order, which became universal over the ashes of the Soviet Union, could now be facing its sunset. This, not only because its main challenger, China, may strengthen its geopolitical position in the face of its rival alliances’ disruption, but, more significantly, because the U.S. itself may cease to champion it.

Feature Image Credit: www.brookings.edu

Occasional Paper: 9/2024

China and the US: Conventional and Nuclear Military Strategies

Abstract

China’s military strategy focuses on developing asymmetric capabilities to counter the United States’ technological advantages and superior military budget by investing in precision missiles, advanced targeting systems, and system destruction warfare. The US initiated the Defence Innovation Initiative to prioritise autonomous learning systems and high-speed projectiles; however, it diminished under the Trump administration, leaving the US reliant on legacy weapons systems vulnerable to new-generation autonomous and hypersonic weapons. Despite China’s advancements, the US maintains a significant advantage in nuclear warheads, with 5,800 compared to China’s 320 in 2020, consistent with Mao’s “minimum deterrent” strategy. While China’s nuclear arsenal primarily comprises strategic weapons, the US possesses both tactical and strategic types. The US complacency regarding China’s military challenge may stem from its nuclear superiority; however, as China progresses technologically, the US risks falling behind by relying on outdated weapons systems, often maintained due to their economic significance in key congressional districts.

Key Words: #nuclear warheads, #hypersonic weapons, #precision weapons, #asymmetric capabilities, #system destruction warfare, #autonomous learning systems

Introduction

Since the beginning of the millennium, China has decided to outsmart the United States’ military strength through a very particular strategy. It aimed at overcoming America’s technological advantages and much superior military budget by investing significant resources in asymmetrical capabilities. As Mark Leonard wrote, China was attempting to become an “asymmetric superpower” outside the realm of conventional military power (Leonard, 2008, p. 106).

Asymmetric superpower

Conscious that the Soviet Union had driven itself into bankruptcy by accepting a ruinous competition for military primacy with the US, China looked for cheaper ways to compete. As a result, it invested billions in an attempt to make a generational leap in military capabilities, able to neutralize and trump America’s superior conventional forces. In other words, instead of rivalling the United States on its own game, it searched to engage it in a different game altogether. It was the equivalent of what companies like Uber, Netflix, Airbnb or Spotify did in relation to the conventional economic sectors with which they competed. A novel by P.W. Singer and August Cole depicts how, through surprise and a whole array of asymmetric weapons, China defeats the superior forces of the United States (Singer and Cole, 2016).

In essence, these weapons are dual-focused. On the one hand, they emphasize long and intermediate-range precision missiles and advanced targeting systems, able to penetrate battle network defences during the opening stages of a conflict. On the other hand, they aim at systems destruction warfare, able to cripple the US’ command, control, communication and intelligence battle network systems. The objective in both cases is to target the US’ soft spots with weapons priced at a fraction of the armaments or systems that they strive to destroy or render useless. The whole notion of asymmetric weapons, indeed, is based on exploiting America’s military weaknesses (like its dependence on information highways or space satellites) while neutralizing its strengths (like its fleet of aircraft carriers). Michael Pillsbury describes this situation in graphic terms: “For two decades, the Chinese have been building arrows designed to find a singular target – the Achilles’ heel of the United States” (Pillsbury, 2015, p. 196).

America’s military legacy systems

To counter China’s emerging military threat, the Obama administration put in motion what it called the Defence Innovation Initiative. This was also known as the Third Offset Strategy, as it recalled two previous occasions in the 1950s and the 1970s when, thanks to its technological leaps, the US could overcome the challenges posed by the Soviet military. Recognizing that the technological superiority, which had been the foundation of US military dominance for years, was not only eroding but was being challenged by China, the Pentagon defined a series of areas to be prioritized. Among them were the following: Autonomous learning systems, human-machine collaborative decision-making, network-enabled autonomous weapons, and high-speed projectiles (Ellman, Samp and Coll, 2017).

However, as with many other initiatives representing the Obama legacy, this one began fading into oblivion with Trump’s arrival to power. As a result, the vision of significantly modernizing America’s military forces also faded (McLeary, 2017). This implied reverting to the previous state of affairs, which still lingers nowadays. In Raj M. Shah and Christopher M. Kirchhoff’s words: “We stand at the precipice of an even more consequential revolution in military affairs today. A new way of war is bearing down on us. Artificial-intelligence-powered autonomous weapons are going global. And the US military is not ready for them (…). Yet, as this is happening, the Pentagon still overwhelmingly spends its dollars on legacy weapons systems. It continues to rely on an outmoded and costly technical production system to buy tanks, ships and aircraft carriers that a new generation of weapons – autonomous and hypersonic – can demonstrably kill” (Shah and Kirchhoff, 2024).

Legacy systems -aircraft carriers, fighter jets, tanks – are deliberately manufactured in key congressional districts around the country so that the argument over whether a weapons system is needed gets subsumed by the question of whether it produces jobs

Indeed, as Fareed Zakaria put it: “The United States defence budget is (…) wasteful and yet eternally expanding (…). And the real threats of the future -cyberwar, space attacks- require different strategies and spending. Yet, Washington continues to spend billions on aircraft carriers and tanks” (Zakaria, 2019). A further quote explains the reason for this dependence on an ageing weapons inventory: “Legacy systems -aircraft carriers, fighter jets, tanks – are deliberately manufactured in key congressional districts around the country so that the argument over whether a weapons system is needed gets subsumed by the question of whether it produces jobs” (Sanger, 2024, p. 193). Hence, while China’s military advances towards a technological edge, America’s seems to be losing both focus and fitness.

Minimum deterrence nuclear strategy

Perhaps this American complacency concerning China’s disruptive weapons and overall military challenge could be explained by an overreliance on its nuclear superiority. Indeed, in 2020, in the comparison of nuclear warheads, the United States possessed overwhelming superiority with 5,800 against China’s 320 (Arms Control Association, 2020). This was consistent with the legacy of Mao’s “minimum deterrent” strategy. Within the above count, two kinds of nuclear weapons are involved – tactical and strategic. The former, with smaller explosive capacity, are designed for use in battlefields. With a much larger capacity, the latter aims at vital targets within the enemy’s home front. In relation to tactical nuclear weapons, America’s superiority is total, as China doesn’t have any. Nonetheless, in terms of long-range, accuracy, and extensive numbers, China’s conventional ballistic missiles (like the DF-26, also known as the Guam killer) can become an excellent match to the US’ tactical nuclear weapons (Roblin, 2018). The big difference between both countries, thus, is centred on America’s overwhelming superiority in strategic nuclear warheads.

China’s minimum deterrent nuclear strategy was based on the assumption that, within cost-benefit decision-making, a limited nuclear force, able to target an adversary’s strategic objectives, could deter a superior nuclear force. This required retaliatory strike capacities that can survive a first enemy attack. In China’s case, this is attainable through road-mobile missiles that are difficult to find and destroy, and by way of missiles based on undetectable submarines. Moreover, Beijing’s hypersonic glide vehicle -whose prototype was successfully tested in July 2021- follows a trajectory that American systems cannot track. All of these impose restraint in the use of America’s more extensive arsenal and undermine its ability to carry out nuclear blackmail.

there is no US defence that “could block” China’s hypersonic glide vehicle “not just because of its speed but also due to its ability to operate within Earth’s atmosphere and to change its altitude and direction in an unpredictable manner while flying much closer to the Earth’s surface”

For the above aim, Beijing has developed new nuclear ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and a sea-based delivery system. These include the DF-41 solid-fuel road-mobile intercontinental ballistic missile (with a range of 15,000 kilometres) or the submarine-launched JL-3 solid-fuel ballistic missile (whose range is likely to exceed 9,000 kilometres). To launch the JL-3 missiles, China counts with four Jin-class nuclear submarines, with an upgraded fifth under construction, each armed with twelve nuclear ballistic missiles (Huang, 2019; Panda, 2018). On top of that, there is no US defence that “could block” China’s hypersonic glide vehicle “not just because of its speed but also due to its ability to operate within Earth’s atmosphere and to change its altitude and direction in an unpredictable manner while flying much closer to the Earth’s surface” (Sanger, 2024, p. 190). All of this shows that America’s overwhelming superiority in terms of strategic nuclear warheads results in more theoretical than practical. What might justify a first American strategic nuclear strike on the knowledge that a Chinese retaliatory one could destroy New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, or all of the three together?

Matching the US’ overkill nuclear capacity

Being an asymmetric superpower while sustaining a minimum but highly credible deterrent nuclear strategy implied much subtility in terms of military thinking. One, in tune with the best Chinese traditions exemplified by Sun Tsu’s The Art of War and Chan-Kuo T’se’s Stratagems of the Warring States. However, in this regard, as in many others, Xi Jinping is sowing rigidity where subtility and flexibility prevailed. A perfect example of this is provided by its intent to match the US in terms of strategic nuclear warheads. In David E. Sanger’s words: “But now, it seemed apparent, Chinese leaders had changed their minds. Xi declared that China must ‘establish a strong strategic deterrence system’. And satellite images from near the cities of Yumen and Hami showed that Xi was now ready to throw Mao’s ‘minimum deterrent’ strategy out of the window” (Sanger, 2024, p. 200).

Three elements attest to the former. Firstly, 230 launching silos are under construction in China. Secondly, these silos are part of a larger plan to match the US’ “triad” of land-launched, air-launched, and sea-launched nuclear weapons. Thirdly, it is estimated that by 2030, China will have an arsenal of 1,000 strategic nuclear weapons, which should reach 1,500 by 2035. The latter would imply equalling the Russian and the American nuclear strategic warheads (Sanger, 2024, p. 197; Cooper, 2021; The Economist, 2021; Hadley, 2023).

Xi Jinping is thus throwing overboard the Chinese capability to neutralize America’s strategic nuclear superiority at a fraction of its cost, searching to match its overkill capacity. In essence, nuclear arms seek to fulfil two main objectives. In the first place, intimidating or dissuading into compliance a given counterpart. In the second place, deterring by way of its retaliatory capacity, any first use of nuclear weapons by a counterpart.

As seen, the second of those considerations was already guaranteed through its minimum deterrence strategy. In relation to the first, China already enjoys a tremendous dissuading power and the capacity to neutralize intimidation in its part of the world. Indeed, it holds firm control over the South China Sea. This is for three reasons. First, through its possession and positioning there, of the largest Navy in the world. Second, by way of the impressive firepower of its missiles, which includes the DF21/CSS-5, capable of sinking aircraft carriers more than 1,500 miles away. Third, via the construction and militarization of 27 artificial islands in the Paracel and Spratly archipelagos. All of this generates an anti-access and denial of space synergy, capable of being activated at any given time against hostile maritime forces. In other words, China cannot be intimidated into compliance by the United States in the South China Sea scenario (Fabey, 2018, pp. 228-231). Nor, in relation to Taiwan, could America’s superior nuclear forces dissuade Beijing to invade if it so decides. The US, indeed, would not be willing to trade the obliteration of Los Angeles or any other of its major cities by going nuclear in the defence of Taiwan.

Simultaneously confronting two gunfighters

It was complicated enough during the Cold War to defend against one major nuclear power. The message of the new [Chinese] silos was that now the United States would, for the first time in its history, must think about defending in the future against two major nuclear powers with arsenals roughly the size of Washington’s – and be prepared for the possibility that they might decide to work together

Matching the US’ nuclear overkill capacity will not significantly alter the strategic equation between both countries. If anything, it would only immobilize in easy-to-target silos, the bulk of its strategic nuclear force. However, Xi’s difficult-to-understand decision makes more sense if, instead of thinking of two nuclear powers, we were to think of a game of three. This would entail a more profound strategic problem for the United States that David E. Sanger synthesizes: “It was complicated enough during the Cold War to defend against one major nuclear power. The message of the new [Chinese] silos was that now the United States would, for the first time in its history, must think about defending in the future against two major nuclear powers with arsenals roughly the size of Washington’s – and be prepared for the possibility that they might decide to work together” (Sanger, 2024, p. 201). This working together factor should be seen as the new normal, as a revisionist block led by China and Russia confronts America’s system of alliances and its post-WWII rules-based world order.

Although the United States could try to increase the number of its nukes, nothing precludes its two competitors from augmenting theirs as well, with the intention of maintaining an overwhelming superiority. According to Thomas Schelling, leading Game Theory scholar and Economics Nobel Prize winner, the confrontation between two nuclear superpowers, in parity conditions, was tantamount to that of two far-west gunfighters: Whoever shot first had the upper hand. This is because it can destroy a significant proportion of its counterpart’s nuclear arsenal (Fontaine, 2024). In the case in point, Uncle Sam would have to simultaneously confront two gunfighters, each matching his skills and firepower. Although beyond a certain threshold, there wouldn’t seem to exist a significant difference in the capacity of destruction involved, nuclear blackmail could be imposed upon the weakest competitor. In this case, the United States.

Conclusion

From an American perspective, overreliance on its challenged nuclear power makes no sense. Especially if it translates into a laid-back attitude in relation to the current technological revolution in conventional warfare. If Washington doesn’t go forward with a third offset military strategy, it could find itself in an extremely vulnerable position. Just two cases can exemplify this. Aircraft carriers are becoming obsolete as a result of the Chinese DF21-CSS5 missile, able to sink them 1,500 miles away, in the same manner in which war in Ukraine is showing the obsolescence of modern tanks when faced with portable Javelins and drones. If the US is not able to undertake a leap forward in conventional military weapons and systems, it will be overcome by its rivals in both conventional and nuclear forces. For Washington, no doubt about it, this is an inflexion moment.

References:

Arms Control Association (2020). “Nuclear weapons: Who has what at a glance”, August.

Cooper, Helene (2021). “China could have 1,000 nuclear warheads by 2030, Pentagon says”. The New York Times, November 3.

Ellman, Jesse, Samp, Lisa, Coll, Gabriel (2017). “Assessing the Third Offset Strategy”. Center for Strategic & International Studies, CSIS, March.

Fabey, Michael (2018) Crashback: The Power Clash Between US and China in the Pacific. New York: Scribner.

Fontaine, Phillipe (2024). “Commitment, Cold War, and the battles of self: Thomas Schelling on Behavior Control”. Journal of the Behavioral Sciences, April.

Hadley, Greg (2023). “China Now Has More ICBM Launchers than the US”. Air & Space Forces Magazine. February 7.

Huang, Cary (2019). “China’s show of military might risk backfiring”. Inkstone, October 19.

Leonard, Mark (2008). What Does China Think? New York: HarperCollins.

McLeary, Paul (2017). “The Pentagon’s Third Offset May be Dead, But No One Knows What Comes Next”. Foreign Policy, December 18.

Panda, Ankit (2018). “China conducts first test of new JL-3 submarine-launched ballistic missile”. The Diplomat, December 20.

Pillsbury, Michael (2015). The Hundred-Year Marathon. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Roblin, Sebastien (2018). “Why China’s DF-26 Missile is a Guam Killer”. The National Interest, November 9.

Sanger, David E. (2024). New York: Crown Publishing Books.

Shah, Raj M. and Kirchhoff, Christopher M. (2024). “The US Military is not Ready for the New Era of Warfare”. The New York Times, September 13.

Singer, P.W. and Cole, August (2016). Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War. Boston: Eamon Dolan Book.

The Economist (2021). “China’s nuclear arsenal has been extremely modest, but that is changing”, November 20.

Zakaria, Fareed (2019). “Defense spending is America’s cancerous bipartisan consensus”. The Washington Post, July 18.

Feature Image Credit: NikkeiAsia

Text Image: AsiaTimes.com

All foreign policies must aim at attaining purpose, credibility, and efficiency. Purpose defines the main objectives that the country wishes to achieve through its international relations. Credibility comes from international recognition of its actions in this field. And efficiency allows implementation, at the lowest possible cost, of the desired purpose. These three notions, although interwoven and influencing each other, keep their own specificity.

How does Xi Jinping’s foreign policy qualify in these three areas?

Purpose

Its purpose, in tune with that of the Chinese Communist Party before his arrival to power, is sufficiently clear. By 2049, the centenary of the founding of the People’s Republic, China should have achieved a prominence commensurate to its glorious past. According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, China marches towards the perception of its global destiny with a clear strategy in mind. Such destiny is none other than the resurrection of its historical glory (Rudd, 2017). Projects such as the Chinese Dream of National Rejuvenation, Made in China 2025, and the Belt and Road Initiative, converge in defining concrete goals that lead in that direction. This includes China’s “Great Unification” with Taiwan, the consolidation of a hegemonic position within the South China Sea, making China the epicentre of an Asian-led world economic order, and creating a global infrastructure and transportation network with China at its head. Xi Jinping visualizes the next ten to fifteen years as a window of opportunity to shift China’s correlation of power with the United States. Hence, Beijing seeks the convergence of energies and political determination towards this window of opportunity. The strategic compass of Xi’s foreign policy could not be more precise. Few countries show a clearer sense of its purpose.

Credibility

His foreign policy credibility presents a more mixed result. Vis-à-vis the Western World and several of its neighbours, China’s credibility is at a very low point. However, the situation is different in relation to the Global South, where Xi’s foreign policy promotes four interconnected initiatives to expand China’s influence. Besides the Belt and Road, whose objective is creating a China-led global infrastructure and transportation network, there is also the Global Development Initiative, the Global Security Initiative, and the Global Civilization Initiative. The first, the Global Development Initiative, aims to contrast the unequal distribution of benefits that characterize the West-led development projects with the inclusiveness and balanced nature of this China-led multilateral development project [Hass, 2023]. The other two initiatives, global security and global civilization, present rational and balanced options clearly differentiated from America’s overbearing approach to these areas. In the former case, China’s proposal promotes harmonious solutions to differences among countries through dialogue and consultation [Chaziza, 2023]. The Global Civilization Initiative, on its side, fosters cooperation and interchange between different civilizations, whereby the heterogeneity of cultures and the multiplicity of identities is fully respected [Hoon and Chan, 2023].

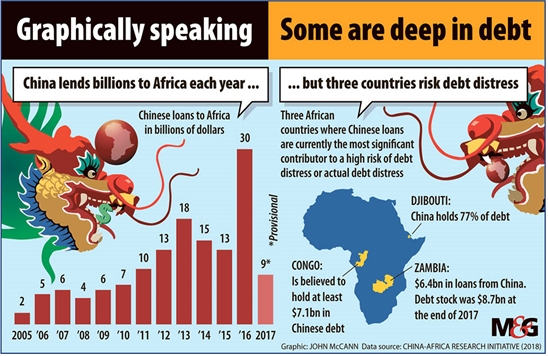

The Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka is one of thousands project that China has helped finance in recent years – Image Credit: The Brussels Times (The so-called China’s debt-trap is a narrative trap).

However, three dark areas emerge in Beijing’s credibility with respect to the Global South. Number one is the frustration prevailing in many of these smaller and underdeveloped nations, resulting from the contradiction between China’s openness as a lender and its severity as a creditor. This has given rise to the suspicion of a hidden agenda on its part and has led to the coining of the phrase “debt trap diplomacy”. Number two derives from the arrogance shown by Beijing towards the rights of several of its weakest neighbours, disregarding international law. This seems to delineate a tributary vision of its relations with them. Although this only affects China’s neighbourhood, it projects a haughtiness that contradicts its formulations about a more harmonious, equitable and inclusive world order. Number three is the apparent contradiction between Beijing’s proclamation regarding the value of the heterogeneity of cultures and the diversity of identities and its treatment of non-Han Chinese minorities at home. A feature susceptible to reproducing itself abroad. All the above generates a distance between words and deeds that casts a shadow of doubt concerning China’s sincerity. Hence, even within the Global South, China’s credibility shows a mixed result.

Efficiency

Finally, there is the area of efficiency. It is a very complex one, particularly given China’s over-ambitious purpose. It must be said that until 2008, Beijing succeeded in rising as a significant power without alarming neighbours or the rest of the world. It even attained the geopolitical miracle of doing so without alarming the United States. Indeed, few countries have made such a systematic and conscious effort to project a constructive international image as China has done to this date. This included the notion of “peaceful rise”, which implied a path different from that followed by Germany before World War I and Japan during World War II when they tried to overhaul the international political landscape. China’s path, on the contrary, relied upon reciprocity and the search for mutual benefit with other countries. It was a brilliant soft power marketing strategy that gave China huge goodwill dividends (Cooper Ramo, 2007).

“Observe carefully; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership” – Deng Xioping

Regarding its reunification with Taiwan, it relied on “one country, two systems” and the economic benefits of their interconnection as the obvious means to propitiate their joining together. Regarding its maritime disputes in the South China Sea, after having deferred the resolution of this issue to a more propitious moment, it proposed a Code of Conduct to handle it in the least contentious possible manner. In general, similar approach was evident in Beijing’s handling of various contentious issues. Beijing’s leadership followed Deng Xiaoping’s advice to his successors: “Observe carefully; secure our position; cope with affairs calmly; hide our capacities and bide time; be good at maintaining a low profile; and never claim leadership” (Kissinger, 2012, p. 441).

“Like Europe, it has many twenty-first century qualities. Its leaders preach a doctrine of stability and social harmony. Its military talks more about soft than hard power. Its diplomats call for multilateralism rather than unilateralism. And its strategy relies more on trade than war to forge alliances and conquer new parts of the world” – Mark Leonard on China in 2008

Writing in 2008, before the change towards a more assertive foreign policy materialized, Mark Leonard said about China: “Like Europe, it has many twenty-first century qualities. Its leaders preach a doctrine of stability and social harmony. Its military talks more about soft than hard power. Its diplomats call for multilateralism rather than unilateralism. And its strategy relies more on trade than war to forge alliances and conquer new parts of the world” (Leonard, 2008, p. 109). This phrase encapsulates well how China was perceived worldwide, including by the Western World. Not surprisingly, a 2005 world survey on China by the BBC stated that most countries in five continents held a favourable view of that nation. Even more significant was the fact that even China’s neighbours viewed it favourably (Oxford Analytica, 2005). It was a time when all doors opened to China.

2008 represented a turning point. The convergence of several events that year changed China’s perception of its foreign policy role, making it more assertive. Among such events the most significant was the global economic crisis of 2008, the worst crisis since 1929, resulting from America’s financial excesses; other important events were the sweeping efficiency with which China avoided contagion; the fact that China’s economic growth was the fundamental factor in preserving the world from a major economic downturn; and the boost to Chinese self-esteem after the highly successful Beijing Olympic games of that year. In sum, the time in which China had to keep hiding its strengths seemed to have ended.

Although this turning point materialized under Hu Jintao, changes accelerated dramatically after Xi Jinping’s ascend to power. He not only sharpened the edges of the country’s foreign policy but made it more aggressive, even reckless. Xi’s eleven years’ tenure in office has translated into a proliferation of international trouble spots. His overreach and overbearing style misfired, generating a concerted and strong reaction against China. As a result, the costs linked to attaining China’s purpose have skyrocketed. This deserves a more detailed analysis of China’s foreign policy efficiency under Xi.

Intimidatory policies and actions

Xi Jinping’s intimidatory policies and actions on international affairs have been extensive, bringing with them immense resistance.

After dusting off a plan that had remained on paper for years, Xi decided to build seven artificial islands on top of the South China Sea coral reefs. After assuring President Obama they would not be militarized, he proceeded otherwise. Contravening international maritime law, he assigned 12 nautical miles of Territorial Sea and 200 miles of Exclusive Economic Zone to these artificial outposts.

Under the protection of the People’s Liberation Navy, an oil rig was built in the waters claimed by Vietnam as its EEZ. Disrespecting the International Court of Justice’s ruling about the Philippines’ waters in the South China Sea, China has forcefully enforced its exclusionary presence in them. China’s Coast Guard is now authorized to use lethal force against foreign vessels operating within maritime areas under its jurisdiction claims. This, notwithstanding that China’s claimed jurisdiction, goes far beyond what is recognized by the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea or the International Court of Justice while disputed by several other countries.

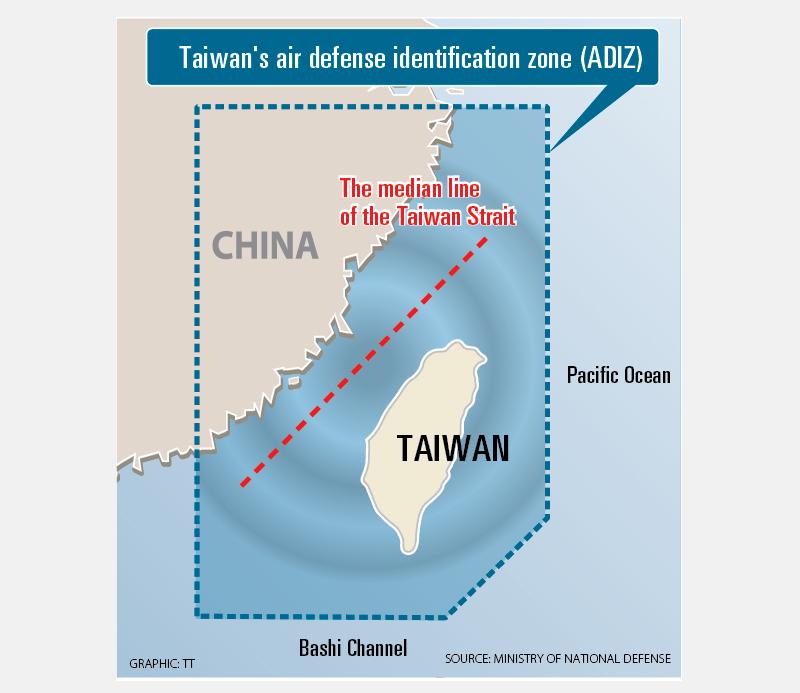

The People’s Liberation Army (PLA) began to ignore the median line in the Taiwan Strait, which it had respected for decades. Frequent and increasingly bold incursions within Taiwan’s Air Defence Identification Zone and reiterated calls to the PLA to prepare for war in Taiwan have become the new normal. The Senkaku-Diaoyu islands, disputed with Japan, have been declared one of China’s core interests, thus closing the door to a negotiated solution. This has translated into the systematic incursion of Chinese maritime law enforcement ships and planes into the territorial and contiguous maritime space of these islands, currently occupied by Japan. Beijing unilaterally imposed an Air Defence Identification Zone over two-thirds of the East China Sea, forcing foreign aircraft to identify themselves under threat of “defensive measures” by the PLA Air Force.

Since 2017, China has reneged on the quite borders with India and engaged in a series of border skirmishes. It has resorted to intrusions into border regions under dispute resulting in a major skirmish in Ladakh with significant casualties, the first since 1987. In 2023, China released an official standard map showing India’s state of Arunachal Pradesh in Northeast India and Askai Chin plateau in the Indian territory of Ladakh in the west, as official parts of its territory, despite India’s objections. At the same time, it renamed 11 places in Arunachal Pradesh with Chinese names. When South Korea decided to deploy the US Army’s THAAD (Terminal High-Altitude Area Defence) ballistic missile defence, as protection against the growing North Korean threat, China put in motion an economic boycott of South Korean products and services. When Australia and New Zealand protested against Chinese interference in their domestic political systems, Beijing openly threatened to impose economic sanctions on governments or private actors criticising China’s behaviour. A few years later, it effectively banned most Australian exports when Canberra proposed an international scientific investigation on the origins of COVID-19. When Canada detained Huawei’s heiress, Meng Wanzhou, answering an American judicial request, Beijing jailed and presented accusations against two Canadian businessmen based in China (releasing them hours after Meng was released).

Antagonizing Americans and Europeans

Xi’s rhetoric in relation to the U.S. has been highly aggressive. Reversing the terms of Deng Xiaoping’s advice to his successors to hide China’s strengths while bidding for right time, Xi has alerted America about its intent to challenge and displace it as the foremost power soon. He has repeatedly referred; to the primacy of China in the emerging world order as its most important objective, to the next ten to fifteen years as the inflexion point when a change in the correlation of power between the two countries should be taking place, to the need to overcome the U.S.’ technological leadership, to the necessity for the PLA to ready itself to wage and win wars, and to the next ten years as a time of confrontation and dangerous storms.

China’s actions have also antagonized the Europeans. These relate to China’s refusal to use the term “invasion” when referring to Russia’s actions in Ukraine; supporting the arguments provided by Russia concerning the causes of the war; placing the responsibility of the conflict on the US and the NATO; abstaining from voting in the U.N. on the West’s resolutions against Russia; demonstrating its strong strategic relations with Russia that is described as “partnership without limits”; the conduct of military exercises with Russia while war rages on in Ukraine; and providing indirect support for Russia’s war effort through surveillance drones, computer chips, and other critical components for its defence industry. Though all of the above are sovereign decisions of China, Europe, as China’s major trading partner, expects some support to their position and a neutral approach to the conflict from China.

For the most part, Beijing’s above foreign policy actions were duly accompanied by a bellicose so-called “wolf warrior diplomacy”. It aggressively reacted to perceived criticism of the Chinese government.

Domestic actions impacting its Image Abroad

However, with its aggressive display in the international arena, some domestic actions have negatively permeated abroad. Brushing aside Deng Xiaoping’s commitment to respect Hong Kong’s autonomy for a period of fifty years, Xi reclaimed complete jurisdiction over such territory since his arrival to power. Within a process of actions and reactions, accelerated by the progressive strangulation of Hong Kong’s liberties, Beijing finally imposed a National Security Law over the territory. This ended the Hong Kong Basic Law, which guaranteed its autonomy. By burying the principle of “one country, two systems” established by Deng, Beijing was, at the same time, closing out any possibility of Taiwan’s willing accession to the People’s Republic. Henceforward, only force may accomplish that result.

On the other hand, the brutal Sinicization of Xinjiang Province has shaken the liberal conscience of Western countries, with particular reference to Europe. The Uyghur population re-education camps have been compared to the Soviet’s Gulag. Beijing’s combative reaction to any foreign criticism in this regard, has compounded China’s image crisis in Europe.

Any remaining trace of the so-called peaceful emergence of China has completely disappeared under Xi Jinping. Under his rudder, China has brought to the limelight a revisionist and tributary vision of the international order. Not surprisingly, interwoven policies and decisions emanating from different geographical points have been converging to contain China. In an unnecessary way, Beijing under Xi has been instrumental in multiplying the barriers to realising its purpose.

Keeping China at bay

The number of initiatives to keep China at bay has multiplied. Its list includes the following. The U.S., Japan, Australia and India created a strategic quadrilateral forum known as the Quad, which is none other than a factual alliance aimed at the containment of China. More formally, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States gave birth to a strategic military alliance with the same goal. On its side, Japan and Australia signed a security cooperation agreement.

Leaving aside its restrained post-war defence policy, Japan doubled its defence budget to 2 per cent of its GDP. This will transform Japan to number three position worldwide regarding military expenditure, just behind the U.S. and China. Within the same context, Japan and the U.S. established a joint command of its military forces while agreeing to create a shared littoral force equipped with the most modern anti-ship missiles. Meanwhile, Japan is set to arm itself with state-of-the-art missiles. Overcoming their longstanding mutual mistrust, Japan and South Korea, jointly with the U.S., established a trilateral framework to promote a rules-based Indo-Pacific region. On the same token, Japan, the Philippines, and the U.S. held a first-ever trilateral summit aimed at defence cooperation and economic partnership. They pledged to protect freedom of navigation and overflight in the South China and East China Seas. Several joint naval exercises have taken place in the South China Sea to defend the principle of freedom of navigation, with France participating in the latest one.

After several fruitless years of attempting to mollify China’s position concerning their maritime dispute in the South China Sea, the Philippines decided to renew its Mutual Defence Treaty with the U.S., which had elapsed in 2016. Meanwhile, most Southeast and East Asian countries on China’s periphery are rapidly increasing their military spending while still continuing to support the U.S. security umbrella. Although pledging to remain neutral, even Vietnam, a traditional de facto ally of China, decided to upgrade its diplomatic relations with Washington to the highest level.

America’s several decades policy of “strategic ambiguity” in relation to Taiwan evaporates as a result of China’s increasing threats and harassment to the island. On top of unambiguous support to Taipei by the President and the Congress, the Pentagon has formulated a military doctrine for Taiwan’s defence in case of invasion. The idea of defending Taiwan if invaded is also taking shape in Japan.

The European Union adhered to the U.S., the United Kingdom and Canada in sanctioning the Chinese authorities involved in human rights abuses in Xinjiang (the first such European sanction since Tiananmen in 1989). Equally, and for the same reasons, the European Parliament refused to ratify the long-time negotiated investment agreement between China and the European Union. China’s aggressive reaction to such a decision only toughened the European position further. Significantly, European contacts with Taiwan have increased as its democratic nature, and China’s harassment of it are providing a new light on the subject. In that context, the European Parliament officially received Taiwan’s Minister of Foreign Affairs.

A gigantic containment Bloc

France and Germany sent warships to navigate the South China Sea in defiance of Beijing’s claimed ownership of 90 per cent of the Sea. NATO’s updated “Strategic Concept” document, which outlines primary threats to the alliance, identified China for the first time as a direct threat to its security: “The People’s Republic of China’s (PRC) stated ambitions and coercive policies challenge our interests, security and values (…) It strives to subvert the rules-based international order, including in the Space, Cyber and Maritime domains (…)The deepening strategic partnership between the People’s Republic of China and the Russian Federation and their mutually reinforcing attempts to undercut the rules-based international order run counter to our values and interests” (NATO, 2022). Not surprisingly, NATO’s last summit included the heads of state and governments of Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea.

As a result of Xi Jinping’s actions and policies, China is now being subjected to a gigantic geostrategic containment force—a true block integrated by nations and organizations from four continents. For a country like China, which traditionally identified with political subtlety and enjoyed universal goodwill until not so long ago, this change in its strategic environment is not a small development. Xi’s calculations that acting boldly had become possible as China was powerful enough, its economy big enough, its neighbours dependent on it, and the U.S. resolve as uncertain have proved wrong and grossly misfired. At this point, China’s conundrum might leave China with few options short of war. According to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, the 2020s have become the “decade of living dangerously”, as, within it, a war between China and the U.S. will most probably erupt (Rudd, 2022, chapter 16).

In sum

An evaluation of Xi Jinping’s foreign policy, using the notions of purpose, credibility, and efficiency as bases, would present the following result. Its purpose is crystal clear, which translates into a high mark. Credibility, on its part, shows mixed results: Not entirely unsatisfactory nor satisfactory. In terms of efficiency, though, Xi Jinping has openly failed. The lack of efficiency associated with his outreach adversely affects the attainment of China’s foreign policy purpose, creating countless barriers to its fulfilment. This lack of efficiency affects the country’s credibility as well. The downturn has been dramatic when comparing the current situation of China’s foreign policy to the one that prevailed before 2008 and, more precisely, to Xi Jinping’s ascension to power.

References:

Chaziza, M. (2023) “The Global Security Initiative: China’s New Security Architecture for the Gulf”, The Diplomat, May 5.

Cooper Ramo, J. (2007). Brand China. London: The Foreign Policy Centre.

Hass, R. (2023) “China’s Response to American-led ‘Containment and Suppression’”, China Leadership Monitor, Fall, Issue 77.

Hoon, C.Y. and Chan, Y.K., (2023) “Reflections on China’s Latest Civilisation Agenda”, Fulcrum, 4 September.

Kissinger, H. (2012). On China. New York: Penguin Books.

Leonard, M. (2008). What Does China Think? New York: Public Affairs.

NATO (2022). “NATO 2022 Strategic Concept”, June 29.

Oxford Analytica (2005). “Survey on China”, September 20th.

Rudd, K. (2022). The Avoidable War. New York: Public Affairs.

Rudd, K. (2017). “Xi Jinping offers a long-term view of China’s ambitions”, Financial Times, October 23.

One of the most influential figures in the field of AI, Ray Kurzweil, has famously predicted that the singularity will happen by 2045. Kurzweil’s prediction is based on his observation of exponential growth in technological advancements and the concept of “technological singularity” proposed by mathematician Vernor Vinge.

The term Singularity alludes to the moment in which artificial intelligence (AI) becomes indistinguishable from human intelligence. Ray Kurzweil, one of AI’s fathers and top apologists, predicted in 1999 that Singularity was approaching (Kurzweil, 2005). In 2011, he even provided a date for that momentous occasion: 2045 (Grossman, 2011). However, in a book in progress, initially estimated to be released in 2022 and then in 2024, he announces the arrival of Singularity for a much closer date: 2029 (Kurzweil, 2024). Last June, though, a report by The New York Times argued that Silicon Valley was confronted by the idea that Singularity had already arrived (Strifeld, 2023). Shortly after that report, in September 2023, OpenAI announced that ChatGPT could now “see, hear and speak”. That implied that generative artificial intelligence, meaning algorithms that can be used to create content, was speeding up.

Is, thus, the most decisive moment in the history of humankind materializing before our eyes? It is difficult to tell, as Singularity won’t be a big noticeable event like Kurzweil suggests when given such precise dates. It will not be a discovery of America kind of thing. On the contrary, as Kevin Kelly argues, AI’s very ubiquity allows its advances to be hidden. However, silently, its incorporation into a network of billions of users, its absorption of unlimited amounts of information and its ability to teach itself, will make it grow by leaps and bounds. And suddenly, it will have arrived (Kelly, 2017).

The grain of wheat and the chessboard

What really matters, though, is the gigantic gap that will begin taking place after its arrival. Locked in its biological prison, human intelligence will remain static at the point where it was reached, while AI shall keep advancing at exponential speed. As a matter of fact, the human brain has a limited memory capacity and a slow speed of processing information: About 10 Hertz per second (Cordeiro, 2017.) AI, on its part, will continue to double its capacity in short periods of time. This is reminiscent of the symbolic tale of the grain of wheat and the chess board, which takes place in India. According to the story, if we place one grain of wheat in the first box of the chess board, two in the second, four in the third, and the number of grains keeps doubling until reaching box number 64, the total amount of virtual grains on the board would exceed 18 trillion grains (IntoMath). The same will happen with the advance of AI.

The initial doublings, of course, will not be all that impressive. Two to four or four to eight won’t say much. However, according to Ray Kurzweil, the moment of transcendence would come 15 years after Singularity itself, when the explosion of non-human intelligence should have become overwhelming (Kurzweil, 2005). But that will be only the very beginning. Centuries of progress would be able to materialize in years or even months. At the same time, though, centuries of regression in the relevance of the human race could also occur in years or even months.

Humans equaling chickens

As Yuval Noah Harari points out, the two great attributes that separate homo sapiens from other animal species are intelligence and the flow of consciousness. While the first has allowed humans to become the owners of the planet, the second gives meaning to human life. The latter translates into a complex interweaving of memories, experiences, sensations, sensitivities, and aspirations: meaning, the vital expressions of a sophisticated mind. According to Harari, though, human intelligence will be utterly negligible compared to the levels to be reached by AI. In contrast, the flow of consciousness will be an expression of capital irrelevance in the face of algorithms’ ability to penetrate the confines of the universe. Not in vain, in his terms, human beings will be to AI the equivalent of what chickens are for human beings (Harari, 2016).

Periodically, humanity goes through transitional phases of immense historical significance that shake everything on its path. During these, values, beliefs and certainties are eroded to their foundations and replaced by new ones. All great civilizations have had their own experiences in this regard. In the case of the Western World, there have been three significant periods of this kind in the last six hundred years: The Renaissance that took place in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Enlightenment of the 18th, and Modernism that began at the end of the 19th century and reached its peak in the 20th.

Renaissance, Enlightenment and Modernism

The Renaissance is understood as a broad-spectrum movement that led to a new conception of the human being, transforming it in the measure of all things. At the same time, it expressed a significant leap in scientific matters where, beyond great advances in several areas, the Earth ceased to be seen as the centre of the universe. The Enlightenment placed reason as the defining element of society. Not only in terms of the legitimacy of political power but also as the source of liberal ideals such as freedom, progress, or tolerance. It was, concurrently, the period in which the notion of harmony was projected into all orders, including the understanding of the universe. During this time, the scientific method began to be supported by verification and evidence. Enlightenment represented a new milestone in the self-gratifying vision human beings had of themselves.

Modernism, understood as a movement of movements, overturned prevailing paradigms in almost all areas of existence. Among its numerous expressions were abstract art in its multiple variables, an introspective narrative that gave a free run to the flow of consciousness, and psychoanalysis, the theatre of the absurd. In sum, reason and harmony were turned upside down at every step. Following its own dynamic but feeding back the former, science toppled down the pillars of certainty. This included the conception of the universe built by Newton during the Enlightenment. The conventional notions of time and space lost all meaning under the theory of Relativity while, going even further, quantum physics made the universe a place dominated by randomness. Unlike the previous two periods of significant changes, Modernism eroded to its bones the self-gratifying vision human beings had of themselves.

The end of human centrality

Renaissance, Enlightenment and Modernism unleashed and symbolized new ways of perceiving the human being and the universe surrounding him. Each of these movements placed humanity before new levels of consciousness (including the subconscious during Modernism). In each of them, humans could feel themselves more or less valued, more secure or insecure with respect to their own condition and its position in relation to the universe itself. However, a fundamental element was never altered: Humans always studied themselves and their surroundings. Even while questioning their nature and motives, they reaffirmed their centrality within the planet. As it had been defined since the Renaissance, humans kept being the measure of all Earthly things.

Singularity, however, is called to destroy that human centrality in a radical, dramatic, and irreversible way. As a result, human beings will not only confront its obsolescence and irrelevance but will embark on the path towards becoming equals to chickens. Everything previously experienced in the march of human development, including the three above-mentioned groundbreaking periods, will pale drastically by comparison.

The countdown towards the end

We are, thus, within the countdown towards the henhouse grounds. Or worse still, towards the destruction of the human race itself. That is what Stephen Hawking, one of the most outstanding scientists of our time, believed would result from the advent of AI’s dominance. This is also what hundreds of top-level scientists and CEOs of high-tech companies felt when, in May 2023, they signed an open letter warning about the risk to human subsistence involved in an uncontrolled AI. For them, the risk for humanity associated with this technology was on par with those of a nuclear war or a devastating human pandemic. Furthermore, at a “summit” of bosses of large corporations held at Yale University in mid-June this year, 42 percent indicated that AI could destroy humanity in five to ten years (Egan, 2023).

The risk for humanity associated with AI technology was on par with those of a nuclear war or a devastating human pandemic. At a “summit” of bosses of large corporations held at Yale University in mid-June this year, 42 percent indicated that AI could destroy humanity in five to ten years.

In the short to medium term, although at the cost of increasing and massive unemployment, AI will spurt gigantic advances in multiple fields. Inevitably, though, at some point, this superior intelligence will escape human control and pursue its own ends. This may happen if freed from the “jail” imposed by its programmers by some interested hand. The natural culprits of these actions would come from what Harari labels as the community of experts. Among its members, many believe that if humans can no longer control the overwhelming volumes of information available, the logical solution is to pass the commanding torch to AI (Harari, 2016). The followers of the so-called Transhumanist Party in the United States represent a perfect example of this. They aspire to have a robot as President of that country within the next decade (Cordeiro, 2017). However, AI might be able to free itself of human constraints without any external help. Along the road, its own self-learning process would certainly allow so. One way or the other, when this happens, humanity will be doomed.

As a species, humans do not seem to have much of an instinct for self-preservation. If nuclear war or climate change doesn’t get rid of us, AI will probably take care of it. The apparently imminent arrival of Singularity, thus, should be seen with frightful eyes.

References

Cordeiro, José Luis (2017). “En 2045 asistiremos a la muerte de la muerte”. Conversando con Gustavo Núñez, AECOC, noviembre.

Egan, Matt (2023). “42% of CEOs say AI could destroy humanity in five to ten years”, CNN Business, June 15.

Harari, Yuval Noah (2016). Homo Deus. New York: Harper Collins.

Grossman, Lev (2011) “2045: The Year the Man Becomes Inmortal”, Time, February 10.

IntoMath, “The Wheat and the Chessboard: Exponents.

Kelly, Kevin (2017). The Inevitable. New York: Penguin Books.

Kurzweil, Ray (2005). The Singularity is Near. New York: Viking Books.

Kurzweil, Ray (2024). The Singularity is Nearer. New York: Penguin Random House.

Streifeld, David (2023). “Silicon Valley Confronts the Idea that Singularity is Here”, The New York Times, June 11.

Feature Image Credit: Technological Singularity https://kardashev.fandom.com

Text Image: https://ts2.space

Ambassador Alfredo Toro Hardy examines, in this excellently analysed paper, the self-created problems that have contributed to America’s declining influence in the world. As he rightly points out, America helped construct the post-1945 world order by facilitating global recovery through alliances, and mutual support and interweaving the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments. The rise of neoconservatism following the end of the Cold War, particularly during the Bush years from 2000 to 2008, led to American exceptionalism, unipolar ambitions, and the failure of American foreign policy. Obama’s Presidency was, as Zbigniew Brezinski said, a second chance for restoring American leadership but those gains were nullified in Donald Trump’s 2016-20 presidency leading to the loss of trust in American Leadership. In a final analysis that may be questionable for some, Ambassador Alfredo sees Biden’s administration returning to the path of liberal internationalism and recovering much of the lost trust of the world. His fear is that it may all be lost if Trump returns in 2024. – Team TPF

TPF Occasional Paper 9/2023

In seeking his second nonconsecutive term, former President Donald Trump will start out in a historically favourable position for a presidential primary candidate. Jonathan Ernst/Reuters. fivethirtyeight.com

According to Daniel W. Drezner: “Despite four criminal indictments, Donald Trump is the runaway frontrunner to win the GOP nomination for president. Assuming he does, current polling shows a neck-and-neck race between Trump and Biden in the general election. It would be reckless for other leaders to dismiss the possibility of a second Trump term beginning on January 20, 2025. Indeed, the person who knows this best is Biden himself. In his first joint address to Congress, Biden said that in a conversation with world leaders, he has ‘made it known that America is back’, and their responses have tended to be a variation of “but for how long?”. [1]

A bit of historical context

In order to duly understand the implications of a Trump return to the White House, a historical perspective is needed. Without context, it is difficult to comprehend the meaning of the “but for how long?” that worries so many around the world. Let’s, thus, go back in time.

Under its liberal internationalist grand vision, Washington positioned itself at the top of a potent hegemonic system. One, allowing that its leadership could be sustained by the consensual acquiescence of others. Indeed, through a network of institutions, treaties, mechanisms and initiatives, whose creation it promoted after World War II, the United States was able to interweave the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments. Its alliances were a fundamental part of that system. On the other side of the Iron Curtain, though, the Soviet Union established its own system of alliances and common institutions.

In the 1970s, however, America’s leadership came into question. Two reasons were responsible for it. Firstly, the Vietnam War. The excesses committed therein and America’s impotence to prevail militarily generated great discomfort among several of its allies. Secondly, the crisis of the Bretton Woods system. As a global reserve currency issuer, the stability of the U.S. currency was fundamental. In a persistent way, though, Washington had to run current account deficits to fulfil the supply of dollars at a fixed parity with gold. This impacted the desirability of the dollar, which in turn threatened its position as a reserve currency issuer. When a run for America’s gold reserves showed a lack of trust in the dollar, President Nixon decided in 1971 to unhook the value of the dollar from gold altogether.

Notwithstanding these two events, America’s leadership upon its alliance system would remain intact, as there was no one else to face the Soviet threat. However, when around two decades later the Soviet Union imploded, America’s standing at the top would become global for the same reason: There was no one else there. Significantly, the United States’ supremacy was to be accepted as legitimate by the whole international community because, again, it was able to interweave the exercise of its power with international institutions and legal instruments.

Inexplicable under the light of common sense

In 2001, however, George W. Bush’s team came into government bringing with them an awkward notion about the United States’ might. Instead of understanding that the hegemonic system in place served their country’s interests perfectly well, the Bush team believed that such a system had to be rearranged in tandem with America’s new position as the sole superpower. As a consequence, they began to turn upside down a complex structure that had taken decades to build.

The Bush administration’s world frame became, indeed, a curious one. It believed in unconditional followers and not in allies’ worthy of respect; it believed in ad hoc coalitions and “with us or against us” propositions where multilateral institutions and norms had little value; it believed in the punishment of dissidence and not in the encouragement of cooperation; it believed in preventive action prevailing over international law.

In proclaiming the futility of cooperative multilateralism, which in their perspective just constrained the freedom of action of America’s might, they asserted the prerogatives of a sole superpower. The Bush administration’s world frame became, indeed, a curious one. It believed in unconditional followers and not in allies’ worthy of respect; it believed in ad hoc coalitions and “with us or against us” propositions where multilateral institutions and norms had little value; it believed in the punishment of dissidence and not in the encouragement of cooperation; it believed in preventive action prevailing over international law. Well-known “neoconservatives” such as Charles Krauthammer, Robert Kagan, and John Bolton, proclaimed America’s supremacy and derided countries not willing to follow its unilateralism.

But who were these neoconservatives? They were the intellectual architects of Bush’s foreign policy, who saw themselves as the natural inheritors of the foreign policy establishment of Truman’s time. The one that had forged the fundamental guidelines of America’s foreign policy during the Cold War, in what was labelled as the “creation”. In their view, with the United States having won the Cold War, a new creation was needed. Their beliefs could be summed up as diplomacy if possible, force if necessary; U.N. if possible, ad hoc coalitions, unilateral action, and preemptive strikes if necessary. America, indeed, should not be constrained by accepted rules, multilateral institutions, or international law. At the same time, the U.S.’ postulates of freedom and democracy, expressions of its exceptionalism, entailed the right to propitiate regime change whenever necessary, in order to preserve America’s security and the world order.

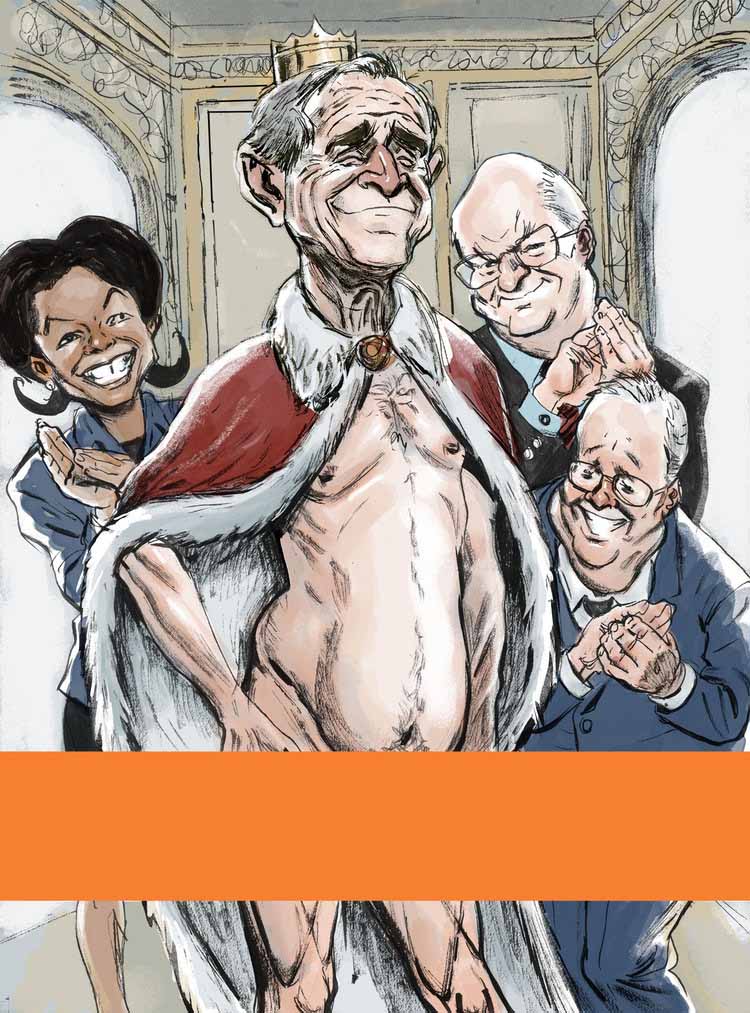

Bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, while deriding and humiliating so many around the world, America’s neoconservatives undressed the emperor. By taking off his clothes, they made his frailties visible for everyone to watch.

Inexplicable, under the light of common sense, the Bush team disassociated power from the international structures and norms that facilitated and legitimized its exercise. As a consequence, America moved from being the most successful hegemonic power ever to becoming a second-rate imperial power that proved incapable of prevailing in two peripheral wars. Bogged down in Iraq and Afghanistan, while deriding and humiliating so many around the world, America’s neoconservatives undressed the emperor. By taking off his clothes, they made his frailties visible for everyone to watch.

At the beginning of 2005, while reporting a Pew Research Center poll, The Economist stated that the prevailing anti-American sentiment around the world was greater and deeper than at any other moment in history. The BBC World Service and Global Poll Research Partners, meanwhile, conducted another global poll in which they asked, “How do you perceive the influence of the U.S. in the world?”. The populations of some of America’s traditional allies gave an adverse answer in the following percentages: Canada 60%; Mexico 57%; Germany 54%; Australia 52%; Brazil 51%; United Kingdom 50%. With such a negative perception among Washington’s closest allies, America’s credibility was in tatters.[2]

Is the liberal international order ending? what is next? dailysabah.com

While Bush’s presidency was reaching its end, Zbigniew Brzezinski wrote a pivotal book that asserted that the United States had lost much of its international standing. This felt, according to the book, particularly disturbing. Indeed, as a result of the combined impact of modern technology and global political awakening, that speeded up political history, what in the past took centuries to materialize now just took decades, whereas what before had taken decades, now could materialize in a single year. The primacy of any world power was thus faced with immense pressures of change, adaptation and fall. Brzezinski believed, however, that although America had deeply eroded its international standing, a second chance was still possible. This is because no other power could rival Washington’s role. However, recuperating the lost trust and legitimacy would be an arduous job, requiring years of sustained effort and true ability. The opportunity of this second chance should not be missed, he insisted, as there wouldn’t be a third one. [3]

A second chance

Barak Obama did certainly his best to recover the space that had been lost during the preceding eight years. That is, the U.S.’s leading role within a liberal internationalist structure. However, times had changed since his predecessor’s inauguration. In the first place, a massive financial crisis that had begun in America welcomed Obama, when he arrived at the White House. This had increased the international doubts about the trustiness of the country. In the second place, China’s economy and international position had taken a huge leap ahead during the previous eight years. Brzezinski’s notion that no other power could rival the United States was rapidly evolving. As a result, Obama was left facing a truly daunting challenge.

To rebuild Washington’s standing in the international scene, Obama’s administration embarked on a dual course of action. He followed, on the one hand, cooperative multilateralism and collective action. On the other hand, he prioritized the U.S.’ presence where it was most in need, avoiding unnecessary distractions as much as possible. Within the first of these aims, Obama seemed to have adhered to Richard Hass’ notion that power alone was simple potentiality, with the role of a successful foreign policy being that of transforming potentiality into real influence. Good evidence of this approach was provided through Washington’s role in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, in the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action in relation to Iran, in the NATO summits, in the newly created G20, and in the summits of the Americas, among many other instances. By not becoming too overbearing, and by respecting other countries’ points of view, the Obama Administration played a leading influence within the context of collective action. Although theoretically being one among many, the United States always played the leading role.[4]

Within this context, Obama’s administration followed a coalition-building strategy. The Trans-Pacific Partnership represented the economic approach to the pivot and aimed at building an association covering forty per cent of the global economy. There, the United States would be the first among equals. As for the security approach to the pivot, the U.S. Navy repositioned its forces within the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans.

To prioritize America’s presence where it was most needed, Obama turned the attention to China and the Asia-Pacific. While America was focusing on the Middle East, China enjoyed a period of strategic opportunity. His administration’s “pivot to Asia” emerged as a result. This policy had the dual objective of building economic prosperity and security, within that region. Its intention was countering, through facts, the notion that America was losing its staying power in the Pacific. Within this context, Obama’s administration followed a coalition-building strategy. The Trans-Pacific Partnership represented the economic approach to the pivot and aimed at building an association covering forty per cent of the global economy. There, the United States would be the first among equals. As for the security approach to the pivot, the U.S. Navy repositioned its forces within the Pacific and the Atlantic oceans. From a roughly fifty-fifty correlation between the two oceans, sixty per cent of its fleet was moved to the Pacific. Meanwhile, the U.S. increased joint exercises and training with several countries of the region, while stationing 2,500 marines in Darwin, Australia. As a result of the pivot, many of China’s neighbours began to feel that there was a real alternative to this country’s overbearing assertiveness.[5]

Barak Obama was on a good track to consolidating the second chance that Brzezinski had alluded to. His foreign policy helped much in regaining international credibility and standing for his country, and the Bush years began to be seen as just a bump on the road of America’s foreign policy. Unfortunately, Donald Trump was the next President. And Trump coming just eight years after Bush, was more than what America’s allies could swallow.

Dog-eat-dog foreign policy

The Bush and Trump foreign policies could not be put on an equal footing, though. The abrasive arrogance of Bush’s neoconservatives, however distasteful, embodied a school of thought in matters of foreign policy. One, characterized by a merger between exalted visions of America’s exceptionalism and Wilsonianism. Francis Fukuyama defined it as Wilsionanism minus international institutions, whereas John Mearsheimer labelled it as Wilsionanism with teeth. Although overplaying conventional notions to the extreme, Bush’s foreign policy remained on track with a longstanding tradition. Much to the contrary, Trump’s foreign policy, according to Fareed Zakaria, was based on a more basic premise– The world was largely an uninteresting place, except for the fact that most countries just wanted to screw the United States. Trump believed that by stripping the global system of its ordering arrangements, a “dog eat dog” environment would emerge. One, in which his country would come up as the top dog. His foreign policy, thus, was but a reflection of gut feelings, sheer ignorance and prejudices.[6]

Trump derided multilateral cooperation and preferred a bilateral approach to foreign relations. One, in which America could exert its full power in a direct way, instead of letting it dilute by including others in the decision-making process. Within this context, the U.S.’ market leverage had to be used to its full extent, to corner others into complying with Washington’s positions. At the same time, he equated economy and national security and, as a consequence, was prone to “weaponize” economic policies. Moreover, he premised on the use of the American dollar as a bullying tool to be used to his country’s political advantage. Not only China but some of America’s main allies as well, were targeted within this approach. Dusting off Section 323 of the 1962 Trade Expansion Act, which allowed tariffs on national security grounds, Trump imposed penalizations in every direction. Some of the USA’s closest allies were badly affected as a result.